Chile and the Pandemic

My experience as a Custer Visiting Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies was outstanding. It was a joy to attend interesting debates about the future, to have access to one of the best libraries in the world, to breathe once again the intellectual vibrancy of a university, to hear Berklee School of Music students perform on several occasions—a real luxury. And I also got to know a group of excellent people and excellent scholars who had obtained fellowships for a semester of research at DRCLAS. Verónica Figueroa Huencho and Mauricio Duce, both from Chile; Luz Horne from Argentina, Beatriz Jaguaribe from Brasil and Juana García Duque from Colombia ended up being part of an adventure we never could have imagined. I had the privilege to be accompanied by my daughter, Camila Bertranou, who, finishing up her university studies, took the opportunity of coming to Cambridge for her personal and professional development.

When I arrived in Cambridge, the coronavirus was a distant disease— like so many other past epidemics, it seemed to be installed mainly in Asia. Things changed very quickly; the contagion spread; classes moved online, and the university shut down its installations, including the DRCLAS offices and finally the library. We decided to go back home after only two months to be close to our family and friends during the pandemic.

My daughter Camila and I, together with Verónica and Mauricio, took a flight to Santiago March 20, subject to multiple changes of schedule, cancellations and quite a bit of uncertainty about whether we could actually get home. The four hours of waiting in the JFK Airport in New York were literally eternal. We were a returning team, four who with diverse necessities and emotions supported each other in a process that was not easy for any of us. While we waited, we saw the U.S. political debate unfold on the television in the airport lounge. We saw President Trump declaring his gratitude to big businesses for the support they almost immediately provided in the effort to do away with the threat. We also watched Governor Cuomo, recognizing the coming crisis would have profound effects for the country and New York in particular. The messages seemed contradictory then, and seen in retrospect the irresponsibility of some political decisions will be analyzed in the human crisis afflicting New York and the United States today.

I’m a frequent traveler, but never have I experienced anything remotely like this time in which we looked with anxiety at the masks and the constant disinfecting, even fearing the very air we breathed. Silence was only broken by worried conversations, intimate memories of interupted trips, separated families and our expectations about finally landing in Chile. We were lucky to get on one of the last flights to Chile from New York.

We arrived and returned to the past.

The day we landed in Chile, only 434 cases of Covid-19 had been recognized by the authorities and very few people had been hospitalized, according to official data. We did two weeks of self-imposed self-quarantine. Quite a few of our friends thought we were reacting in an exaggerated fashion. At the end of the day, it became clear that it was hard for them to understand the possibility of thinking about others, of taking care of oneself to take care of others as a vital decision.

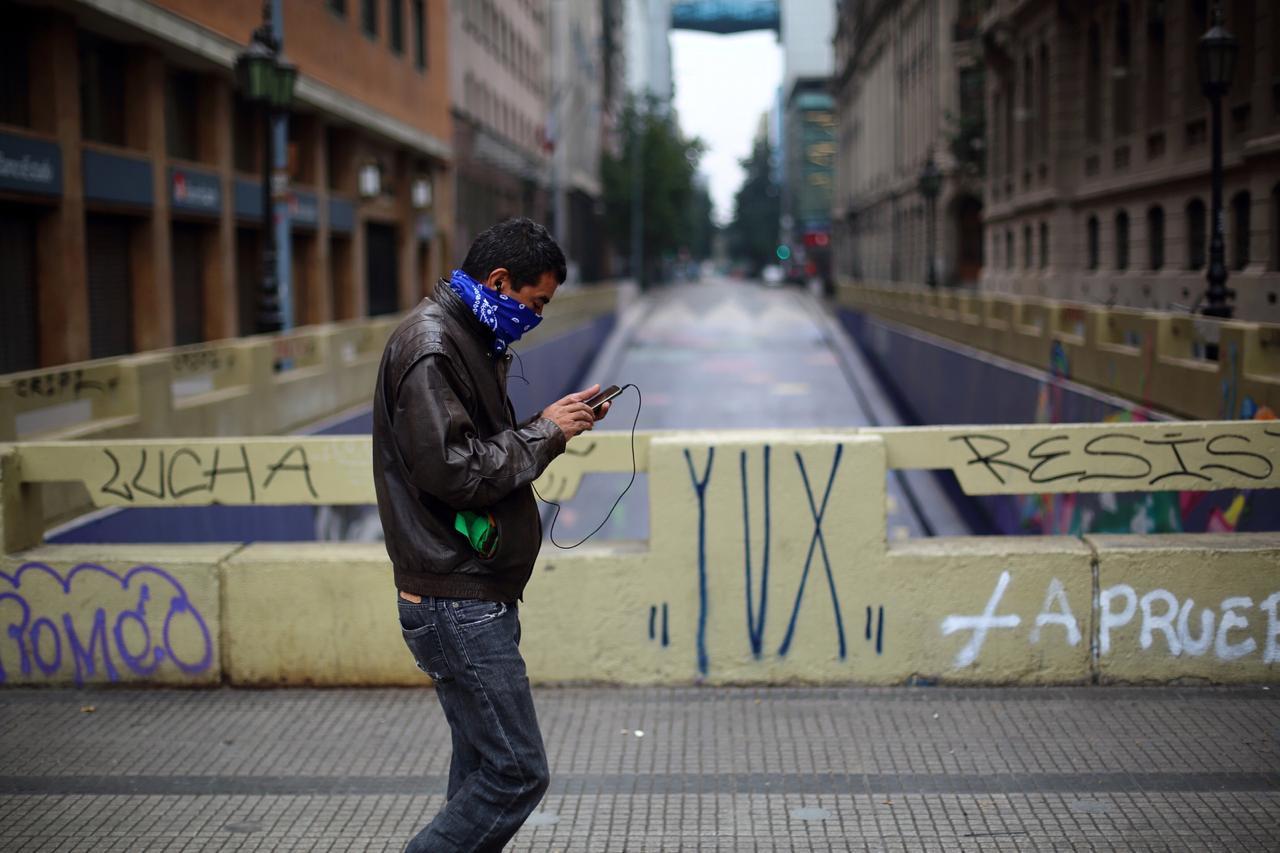

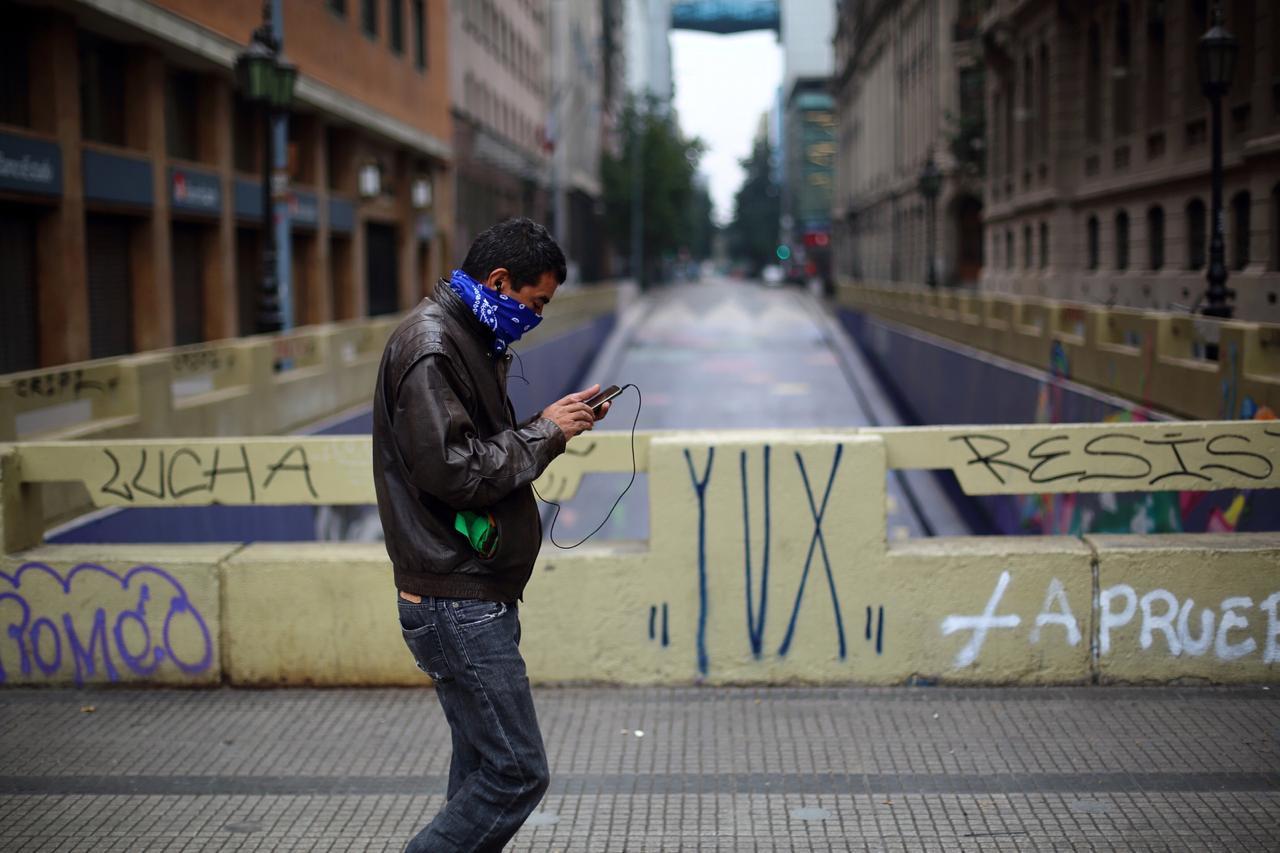

Six weeks have gone by since our return. Like the rest of Latin America, Chile faces the pandemic on several fronts. Unlike Peru or Argentina, Chile has not declared a general quarantine, and it appears that the government is not disposed to take that measure. However, some districts or neighborhoods have decreed a quarantine. The malls are closed and there is a curfew from 10 at night to 6 in the morning. Several voices reclaim with great emphasis the need to impose a quarantine for the metropolitan region (with the greatest concentration of population in Chile) or even a countrywide one. The government response has been to define specific quarantines, based on comunas (districts) with the highest numbers of cases. These tend to be of a higher socio-economic class, those who brought the virus from Europe, the United States and Asia. After several weeks, the presence of the virus and contagion are now distributed throughout the territory; contagion is communitarian, and general anxiety has increased.

The pandemic has uncloaked the inequality of our countries. The quarantine of the better-off contrasts with the lockdown of the poorest and even of the precarious middle class. The same sectors that took to the streets last year today suffer the consequences of a health crisis which will bring profound economic and social transformations in the medium term. Public and private schools have cancelled their in-school classes to go online. We believed that the Internet was a basic product, but in reality, thousands of children and youth are not connected and do not have the basic tools for distance learning. And that’s not to mention the steep learning curve for professors who have to reinvent their teaching techniques. Inequality is a snapshot of precariousness and profound educational difficulty.

Women have an enormous burden in this pandemic. Taking charge of most of the household tasks, as well as the care of children and grandparents, their concern for the duration of the restrictions increases day by day. In the same manner, in spite of the fact that the surge in reported accusations have diminished machista violence and, in general, domestic problems, many worry about the difficulties of thousands of women as they live in quarantine with their abusers. Indeed, the Ministry of Women and Gender Equality revealed that calls to its helpline for domestic abuse increased 70 % in April 2020. Not unlike the way in which the pandemic is playing out in other parts of the world, in Chile, the pandemic also affects women in a different way from men.

The concern about the fate of the economy is at the center of public debate. Many businesses have been deeply affected by the lack of demand, and others such as shopping centers, movie theatres and department stores have been shuttered. The forecasts are overwhelming in a society in which an important part of the citizenry works in the informal sector. Small- and medium-size businesses are for the most part using the tools designed by the government that allow them to maintain workers on their payroll, paying their benefits, but not their salaries. The workers in turn are supported by unemployment benefits, basically the workers’ mandated savings for crisis situations. More than 66,000 businesses had resorted to this mechanism, that is, more than 515,000 workers find themselves in a precarious situation. To this, onc might add the 299,000 employees laid off from large companies. Everyday, one also hears about large firms asking for help from the state to avoid bankruptcy and massive layoffs, and it is still surprising to hear some who previously agitated for the minimum role of the state and the importance of the “invisible hand” of the free market to solve any problem now asking for state help in order to survive.

Social unrest following the pandemic is feared or when the most complex elements of the pandemic materialize in the form of unemployment, lack of access to health care or the collapse of the prison system. In the last few days, we have seen an increase in social conflict in some sectors of society that are demanding structural change, as well as specific measures to confront the pandemic and the economic crisis.

Although experts had some initial disagreements, the government formed an advisory board (whose declarations and resolutions can be found online) that publicly has been collaborating with the government and also debating some of its decisions. Likewise, diverse civil society organizations and experts have paid close attention to the information given by the government, recognizing that epidemiological vigilance is key to decision-making. An example of these reports and proposals can be found on Espacio Público [Public Space] (www.espaciopublico.cl). This process has resulted in the generation of better systems, although far from perfect, to diagnose the problem and the presence of Covid-19 in Chile. The Health Ministry has taken measures such as the mandatory use of masks and the development of tests. We are faced with a permanent process of trial-and-error.

On May 1, 245 people had died of the virus out of 18,435 diagnosed cases. More than 189,000 tests have been performed. Just between May 1 and May 2, the number of cases increased by 1,427, the highest number since the beginning of the pandemic, which shows how far we are from the end of the crisis. As we all now now, the magic to controlling the virus is in testing capacity and contact tracing. The government and experts are working to increase the health system’s capacity, anticipating that during the peak weeks for the virus between the end of April and the beginning of May, there will be enough intensive care hospital beds and artificial respirators. We are above the curve, and it is not clear if it will flatten or be postponed or what will happen, but one thing seems certain: the worst is yet to come.

At the same time, public and private pressure to allow businesses to reopen, to permit movement in the economy and to allow people to return to work is evident. Under discussion is the possibility of soon reopening schools and malls as signs of certain “achievement.” There is also the pressure of national and international experts who stress the danger of opening up spaces without having sufficient tests or contact tracing.

Chile will face the challenge of the pandemic against a very clear backdrop. Citizens’ mass protests in 2019 recognized the necessity to change important parts of the economic model. In particular, the health system, which is privatized, must be transformed; the pensions, which now fluctuate to the rhythm of the stock market, must guarantee subsistance levels; in general, the the subsidiary of the state as defined by the constitution must be changed. The post-pandemia—if we ever get to that stage—also will be one of turbulence, one in which the political world will be obligated to recognize the necessity of structural transformations.

We returned from Cambridge to a Chile in transformation. My stay at Harvard was short but important. Contrary to everything we had planned, it showed me that we learn the most when we are open to listen to differences, to escape from our safe space of tranquility, when the criticism is constructive and finally when we recognize that everything can change from one moment to the other. I am confident that good decisions will allow us to face the pandemic with the least possible human cost and to establish the basis for a new conversation about the very pillars of our democratic systems.

Chile y la pandemia

Por Lucía Dammert

La experiencia en DRCLAS como Custer Visiting Scholar fue excepcional, asistir a interesantes debates sobre el futuro que se está construyendo, acceder a una de las mejores bibliotecas del mundo, respirar el aire universitario nuevamente, escuchar a los alumnos de Berklee en sus múltiples presentaciones artísticas, un lujo. Además, conocí a un grupo de excelentes personas y profesionales que, al igual que yo, habían obtenido la oportunidad de estar un semestre de estudios en Harvard. Verónica Figueroa Huencho y Mauricio Duce, ambos de Chile; Luz Horne de Argentina, Beatriz Jaguaribe de Brasil, y Juana García Duque de Colombia terminaron siendo parte de una aventura que jamás podríamos haber imaginado. Tuve el privilegio además de estar acompañada de mi hija, Camila Bertranou, que terminando sus estudios universitarios, tomaba esta oportunidad para su propio desarrollo personal y profesional.

Cuando llegue a Cambridge, el coronavirus era una enfermedad lejana, como otras epidemias del pasado parecía haberse instalado principalmente en Asia. Las cosas cambiaron muy rápidamente, empezaron los contagios, el paso a las clases on-line, y los cierres de las instalaciones universitarias, nuestras oficinas y finalmente la biblioteca. Decidimos volver, luego de solo dos meses en Cambridge la pandemia la pasaríamos cerca a la familia y los amigos.

Mi hija Camila y yo, junto con Verónica y Mauricio, tomamos el vuelo a Santiago el 20 de marzo, no exentos de cambios de itinerario, cancelaciones y bastante incertidumbre sobre el regreso. Las cuatro horas de espera en JFK fueron literalmente eternas. Fuimos un equipo que regresaba, cuatro que con diversas necesidades y emociones nos apoyamos para un proceso que sin duda no fue fácil para ninguno. Mientras esperamos, la TV mostraba el debate político norteamericano. Vimos al Presidente Trump, con declaraciones que agradecían a las grandes empresas por el apoyo que empezarían a dar de forma inmediata para terminar con la amenaza. También al Gobernador Cuomo, reconociendo que la crisis que se venía sobre el país y especialmente sobre Nueva York tendría profundas consecuencias. El mensaje era al menos contradictorio, y visto en retrospectiva la irresponsabilidad de algunas decisiones políticas seguramente serán analizadas en la crisis humana que atraviesa Nueva York, y Estados Unidos hoy.

He viajado múltiples veces, nunca como esta vez donde todos mirábamos con ansiedad las mascarillas, la desinfección, el mismo aire que respiramos. El silencio solo cambiaba por las conversaciones de preocupación, íntimos recuerdos de viaje interrumpidos, familias separadas y expectativa para el aterrizaje. Tuvimos suerte de subir a uno de los últimos vuelos que salieron a Chile desde Nueva York.

Llegamos y volvimos al pasado.

Ese día solo habían 434 casos de contagio conocidos por las autoridades y pocos hospitalizados, según los datos oficiales, hicimos las dos semanas auto-impuestas de cuarentena preventiva. No fueron pocos los que consideraron que era una exageración de nuestra parte, al final del día, es claro que a muchos les cuesta pensar en el otro, en la posibilidad de cuidarse para cuidar al otro como una decisión vital.

Han pasado ya seís semanas desde nuestro regreso. Al igual que el resto de América Latina, Chile enfrenta la pandemia desde múltiples frentes. A diferencia de países como Perú o Argentina, en Chile no se ha decretado cuarentena generalizada, sino específica en algunos barrios o distritos, y al parecer no está aún entre los planes del gobierno una decisión en esa dirección. Los centros comerciales están cerrados y hay toque de queda desde las 10 de la noche hasta las 6 de la mañana. No son pocas las voces que reclaman con fuerza la necesidad de una cuarentena para la región metropolitana (la de mayor concentración de población) o incluso nacional. La respuesta gubernamental ha sido la definición de cuarentenas especificas a nivel territorial, partiendo por aquellas comunas (distritos) que tenían la presencia de más casos. Las mismas se ubican en los sectores de mayores niveles socioeconómicos, los que trajeron el virus de Europa, Estados Unidos y Asia. Luego de varias semanas, la presencia del virus y la enfermedad se ha distribuido por el territorio, los contagios son comunitarios y la ansiedad ha ido aumentado.

La pandemia ha desnudado la desigualdad de nuestros países. La cuarentena de los sectores más acomodados se enfrenta con el encierro de los más pobres e incluso la precaria clase media. Los mismos sectores que reclamaron en las calles el año pasado, hoy sufren las consecuencias de una crisis sanitaria que traerá profundas transformaciones económicas y sociales en el mediano plazo. Los colegios públicos y privados han cancelado las clases presenciales y se han trasladado a la modalidad “online”. Creíamos que el internet era un producto básico, pero en realidad miles son los niños y jóvenes que no pueden conectarse, que carecen de las herramientas básicas para cumplir con la rutina del estudio a distancia. Sin mencionar el ajuste para profesoras y profesores que han tenido que reinventarse para consolidar mecanismos pedagógicos a distancia. La desigualdad brota por las cuatro esquinas de una foto de precariedad y dificultad educativa profunda.

La carga de las mujeres es enorme en esta pandemia. Encargadas de buena parte de las labores del hogar, así como de las tareas del cuidado y contención de niños y abuelos; la preocupación por la duración de las restricciones aumenta. De igual forma, a pesar que las denuncias han disminuido por violencia machista y en general de problemas al interior de los hogares, existe preocupación por las dificultades que miles de mujeres viven encerradas con sus victimarios. De hecho, el Ministerio de la Mujer y la Equidad de Género reveló que las llamadas al fono de ayuda para las mujeres que lo necesiten puedan recibir la asesoría necesaria en estos casos, aumentaron en el mes de abril 2020 en 70%.

La preocupación por el destino de la economía está en centro de los debates políticos. Si bien múltiples comercios están siendo afectados de forma estructural por la carencia de demanda, algunos otros como centros comerciales, cines y grandes tiendas han sido cerrados. Los pronósticos son abrumadores en una sociedad donde el trabajo independiente representa un porcentaje importante de la población. Las pequeñas y medianas empresas están mayoritariamente usando las herramientas diseñadas por el gobierno que les permiten mantener el vínculo laboral con los trabajadores, pagando cotizaciones pero no el salario. Este último es aportado por las cuentas del seguro de desempleo, básicamente de los ahorros del trabajador para situaciones de crisis. De hecho, más de 66,000 empresas se habían acogido a este mecanismo, es decir más de 515,000 trabajadores están en esta precaria situación. A las que se suman los más de 299 mil despidos principalmente de grandes empresas. Día a día se sabe también de grandes empresas solicitando apoyo del Estado para evitar quiebras y despidos masivos, no deja de sorprender algunas voces que antes apoyaban un Estado pequeño y la importancia de la “mano invisible” del mercado para solucionar cualquier problema; hoy pidiendo apoyo financiero estatal para sobrevivir.

Se teme un estallido social al final de la pandemia, o cuando los elementos mas complejos de la misma se visualicen en el desempleo, la imposibilidad de atención sanitaria o el colapso del sistema carcelario. En los últimos días hemos visto el aumento de conflictividad social en algunos sectores del país que continúan reclamando por cambios estructurales, así como medidas específicas para enfrentar la pandemia y la crisis económica.

Si bien hubo encuentros y desencuentros iniciales entre los especialistas, el gobierno formó un consejo asesor (cuyas actas y resoluciones están online) que públicamente ha ido colaborando y también debatiendo, algunas decisiones del gobierno. De igual forma, diversas organizaciones de la sociedad civil y expertos han estado atentos a la información entregada, reconociendo que la vigilancia epidemiológica es clave para la toma de decisiones. Un ejemplo son los informes y propuestas de Espacio Público (www.espaciopublico.cl). Este proceso ha aportado en la generación de mejores sistemas, aunque lejos de perfectos, para poder diagnosticar el problema y sobretodo su presencia territorial. El Ministerio de Salud ha ido tomando medidas como la obligatoriedad del uso de mascarillas o el desarrollo de testeos. Estamos frente a un proceso de prueba y error permanente.

Al 1 de Mayo el recuento es detallado, han fallecido 245 personas, hay 18,435 contagiados y más de 189,000 tests realizados; solo entre el 1 y 2 de Mayo aumentaron en 1,427 los contagiados alcanzando el número más alto desde el inicio de pandemia, lo que muestra que estamos lejos del final de la crisis. Como ya todos sabemos, la magia está en la capacidad de testeo y trazabilidad de los contagiados. El gobierno y los especialistas están trabajando para aumentar la capacidad del sistema de salud, esperando que las semanas de mayor complejidad que deberían estar entre fines de abril e inicios de mayo, no colapse la oferta de camas de cuidados intensivos o de ventiladores artificiales. Estamos encima de la curva, no está claro si se aplana o se posterga o en definitiva no la podemos ver con claridad pero hay un acuerdo general que lo peor está por venir.

En paralelo la presión pública y privada por buscar cierta normalidad que permita reabrir negocios, permitir movimiento de la economía y potenciar espacios de trabajo es evidente. Se debate la posibilidad de reabrir colegios y centros comerciales en un breve plazo por ejemplo como señales de cierto “logro”. También la presión de especialistas nacionales y extranjeros que plantean el peligro de abrir espacios sin tener capacidad real de testeo y trazabilidad.

Chile, enfrentará el desafío de la pandemia con un telón de fondo muy claro. Las masivas manifestaciones ciudadanas del año 2019 reconocieron la necesidad de cambiar partes importantes del modelo económico. En especial transformar la salud que está privatizada, las pensiones que se mueven al ritmo de la bolsa y no aseguran mínimos de subsistencia, en general cambiar el rol subsidiario del Estado definido así por la Constitución. La postpandemia (si esto es posible de lograr) será un momento turbulento también, uno donde el mundo político se verá obligado a reconocer la necesidad de transformaciones estructurales.

Volvimos a un Chile en transformación. La estadía en Harvard fue corta pero importante. Contrario a todo lo que tenía planificado, esta experiencia me mostró que las mejores lecciones se aprenden cuando estamos abiertos a escuchar diferencias, a salir de nuestros espacios de tranquilidad, cuando la critica es constructiva y finalmente cuando reconocemos que todo puede cambiar de un minuto a otro. Confio que las buenas decisiones nos permitan enfrentar la pandemia con el menor costo humano posible y establezcan las bases de una nueva conversación sobre los pilares mismos de nuestros sistemas democraticos.

Lucia Dammert, Spring 2020 Custer Visiting Scholar at DRCLAS, is a Professor of International Relations at the Universidad de Santiago de Chile. Born in Peru, her research interests lie in the field of public security, criminal organizations and criminal justice reform. Among her most recent books are Fear of Crime in Latin America (2012, Routledge) and Maras (2011, University of Texas Press) edited with Thomas Bruneau. She has held key advisory positions in Chile, Argentina, México and Perú and has served as key advisor at the Organization of American States and other regional organizations. At the global level she has been invited to be part of the UN Secretary General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters.

Lucía Dammert fue DRCLAS Custer Visiting Scholar en la primavera de 2020. Dammert es Profesor Titular de la Facultad de Humanidades de la Universidad de Santiago de Chile. Ha publicado artículos y libros sobre participación comunitaria, seguridad ciudadana, conflictividad social y temas urbanos en revistas nacionales e internacionales. En el plano de la gestión pública ha participado de programas de seguridad ciudadana en diversos países de la Región. Es parte del Consejo Asesor en Temas de Desarme del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas para el periodo 2017-2020 siendo la única representante de América Latina.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...