Brazil’s Vaccinated Democracy

The Life and Times of Zé Gotinha

In March 2021, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a current presidential candidate, posed a pointed question in a speech lambasting President Jair Bolsonaro’s Covid-19 response. “Where is our beloved Zé Gotinha?” Zé Gotinha is not a respected public health expert or crisis manager. Rather, he is an anthropomorphic vaccine droplet that a Los Angeles Times article once described as “an overgrown Casper the Friendly Ghost.”

Zé Gotinha has been a regular fixture in vaccination campaigns in Brazil since his debut in 1986. Artist Darlan Rosa created the character, whose name loosely translates to “Joe Droplet,” to assuage children’s fears of vaccines. But he was conspicuously absent during the early rollout of the Covid-19 vaccines under Bolsonaro, a far-right wing skeptic of vaccines who undermined his own government’s pandemic response. By asking after Zé Gotinha, Lula did more than simply tie his criticism of Bolsonaro to a popular figure known to nearly every Brazilian.

The struggle over Zé Gotinha speaks to deeper questions at the heart of the democratic crisis in Brazil—and across the world. Zé Gotinha’s rise to prominence came just as faith in democracy was at a low point. Brazil had just exited a 21-year military dictatorship (1964-1985). Successive government plans failed to arrest galloping inflation. Introduced as part of an anti-polio campaign, Zé Gotinha became an unlikely symbol of the protections Brazilians expected under democracy.

Brazil enshrined a right to health in the 1988 “Citizen Constitution” and created a new universal healthcare system, the SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde). With Zé Gotinha as its visible symbol often emblazoned with the acronym “SUS,” the vaccination program reached Brazilians of all backgrounds in forgotten rural towns and large cities across the continent-sized nation. Over the years, Zé Gotinha has come to reflect in part a sense that vaccination and protection from deadly diseases is a core tenant of Brazilian citizenship. Bolsonaro attempted to unsettle that conception as part of his broader assault on democratic norms and institutions.

That the mascot would become a political flashpoint seemed improbable when Brazilians first met him. Darlan Rosa created the figure for Brazil’s national immunization program, the PNI, in collaboration with UNICEF. Brazil had joined a global campaign to eradicate polio, a leading cause of infant paralysis. Zé Gotinha owed his appearance to polio vaccines being administered via droplet. Initially nameless, he earned his name after a write-in contest by children.

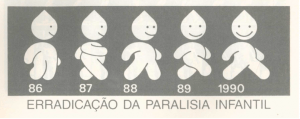

An early image of Zé Gotinha from the 1986 anti-polio campaign. The text reads “Eradication of Infant Paralysis.” Source: Ministério de Saúde (Ministry of Health)

His role was simple, but important. Zé Gotinha walked children through the process of being vaccinated, often through a song or skit. While he himself is a droplet, he also helped children feel less apprehensive about vaccines administered via syringe. He appeared in animated shorts, commercials and print media, as well as in mascot-form at events and in state-run health clinics. In 1990, he even co-starred in a commercial and sing-along with television star and global celebrity Xuxa. As an animated figure, he developed an exuberant, joyful and even playful personality that has become an integral part of his enduring appeal.

Zé Gotinha debuted as Brazil navigated the end of authoritarian rule in 1985. Its nascent democracy struggled to establish itself after the military exerted significant control over the formal political transition. In 1983 and 1984, the largest street protests in Brazilian history, Diretas Já, demanded direct election of the first civilian president. The military and its civilian allies succeeded in ensuring an indirect election via an electoral college, although the candidate of the opposition, Tancredo Neves, won anyway. Just before he took office, however, the respected Neves was hospitalized and ultimately died. His vice-president, José Sarney, assumed the presidency instead. Sarney was a former supporter of the military regime and lacked a significant political base.

Even worse, Sarney faced repeated economic crises and runaway inflation. In 1986, his government issued the first of many stabilization measures, the Plano Cruzado, which quickly collapsed. Over the next eight years, a succession of plans failed to rein in inflation until the Plano Real finally succeeded in 1994. The economic picture compounded a rising sense of insecurity among Brazilians amid perceptions of rising crime.

In contrast, Brazil’s vaccination programs were relatively successful. The polio campaign reached into rural areas in regions like the Amazon far beyond the usual reach of the public healthcare system. For many Brazilians, this was the first time that they had access to life-saving vaccines and healthcare. The last case of polio was recorded in 1989, and the Pan-American Health Organization certified Brazil’s eradication of polio in a ceremony in 1994. Naturally, Zé Gotinha was in attendance. Building on this success, Brazil launched national campaigns or conducted mass vaccination against tetanus, measles, rubella, yellow fever, rotavirus and hepatitis, among others.

Zé Gotinha was a ubiquitous presence across these campaigns that made vaccination a widely accepted part of daily life for Brazilians. The broad acceptance of vaccines continued through the Covid-19 pandemic and into late 2020 when the U.S. FDA gave emergency approval to the first Covid vaccine, making its mass distribution a real possibility. In a January 2021 IPSOS poll of 15 countries, Brazil had the second highest percentage (88%) of people who indicated that they would take a Covid vaccine if offered, only a point behind the United Kingdom. Brazil had the highest percentage of respondents who strongly agreed (72%) that they would take the vaccine compared to the United Kingdom at 67% and the United States at 47%.

That figure was even more remarkable given the response of the Bolsonaro government to the pandemic and vaccines. From the beginning, Bolsonaro dismissed the gravity of the pandemic: he famously called Covid “a little flu” (gripezinha). Bolsonaro then undermined his own government’s ability to acquire and produce vaccines even as he spread misinformation about them. He refused a contract to purchase the Pfizer vaccine at half price. Bolsonaro also deauthorized a purchase order made by his health minister for a vaccine produced through a Chinese-Brazilian collaboration, in part seemingly to take revenge on a former political ally-turned-rival.

Amid pressure from Congress, state governors and civil society, Bolsonaro finally developed a plan to distribute vaccines even as he personally continued professing skepticism about vaccines. On December 16, 2020, his government formally launched the national immunization campaign against Covid-19 with Zé Gotinha in attendance. In a surreal moment, the unmasked Bolsonaro went to shake the hand of the masked Zé Gotinha only to be refused: WHO guidelines discouraged handshaking. It would be the last appearance of Zé Gotinha for months.

Bolsonaro and Zé Gotinha at the December 16, 2020 immunization campaign launch event. Zé Gotinha, attempting to model behavior recommended by health guidelines, declined to shake Bolsonaro’s hand. Instead, Bolsonaro would awkwardly grasp the mascot’s forearm. Photo credit: Sérgio Lima. Source: Poder360.

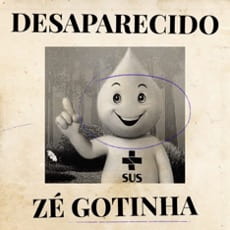

His absence coincided with the worst period of the pandemic in Brazil as Bolsonaro continued to inhibit the vaccine rollout. On March 10, 2021, Lula gave the speech in which he inquired after Zé Gotinha’s whereabouts. He had just been cleared of corruption charges, thus making him eligible to run in the 2022 presidential elections against Bolsonaro. Lula declared that Bolsonaro had “sent [Zé Gotinha] away because he thought he was a petista,” referring to supporter of Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT). The internet immediately ran with the idea, setting off a wave of humorous speculation over what had happened to the famous droplet. Some held that the Zé Gotinha had fallen on hard times while a missing persons poster circulated on social media.

A missing persons poster for Zé Gotinha. Image Credit: @designativista. Source: Mídia Ninja/Twitter.

In response, Eduardo Bolsonaro, the president’s son and a federal congressman, attempted to reframe Zé Gotinha in the image of his family’s far-right brand of politics. He tweeted a militarized image of Zé Gotinha holding a syringe as a rifle and wearing a Brazilian flag as a cape. Many Brazilians were horrified that the children’s mascot was holding a military rifle. Darlan Rosa, Zé Gotinha’s creator, strongly rebutted the younger Bolsonaro stating that Zé Gotinha “was conceived as an educational character. There is nothing educational about a gun.”

Image of Zé Gotinha with a military-style rifle tweeted by Eduardo Bolsonaro on March 12, 2021. Source: Eduardo Bolsonaro/Twitter.

Civil society groups picked up the call for the return of Zé Gotinha. In a March 15, 2021, statement, Brazil’s principal pediatric and immunization associations issued an open letter advocating his return. The letter called for Zé Gotinha in “his original form, joyful, peaceful and motivational” as a symbol of the national vaccination campaign to reinforce the values it represented: “attachment to science, solidarity, the union of forces and, above all, the offer of health and peace.”

These contrasting conceptions of Zé Gotinha underscored the broader political struggle swirling around vaccination. Bolsonaro’s disastrous handling of the pandemic led to a congressional investigation while his approval rating dived.

The stage was set for Zé Gotinha. On May 12, 2021, Bolsonaro’s Ministry of Health launched a new national vaccination campaign. As if to compensate for his prior absence, the media campaign featured a multi-generational family of Zé Gotinhas for the first time. In a commercial for the campaign, the three generations of Zé Gotinhas advocated not only vaccination, but other preventative measures like masking, hand washing and social distancing. Bolsonaro, who rejected all these measures, was notably not present at the launch.

Zé Gotinha and his family at the Mar 12, 2021 launch event. Source: Ministério de Saúde

The return of Zé Gotinha coincided with a turn-around in Brazil’s faltering vaccination efforts. In November 2021, Brazil surpassed the United States in its percentage of vaccinating adults. On social media, commentators attributed the achievement to the culture of vaccination represented in part by Zé Gotinha. As one Twitter user put it, “Brazil will become the most secure country in the pandemic for reasons of: the SUS and [the] culture [of] Zé Gotinha.”

The celebration was marred by further controversy as Bolsonaro continued his attacks on Brazil’s vaccination efforts. On September 30, 2021, the Ministry of Health launched its vaccination program for children younger than 15 years of age. At the launch event, interim Health Minister Rodrigo Cruz, overcome with emotion speaking of his own vaccinated children, began weeping only to be consoled by Zé Gotinha.

Zé Gotinha embraces interim health minister Rodrigo Cruz at the launch event for the national campaign to vaccinate children on September 30, 2021. Photo Credit: Walterson Rosa. Source: Ministério de Saúde.

Bolsonaro, however, declared that he would not vaccinate his 11-year-old daughter and sparred with the government agency that approved the vaccines for children. The internet once again posted humorous takes about Zé Gotinha being put in prison for encouraging the vaccination of children. On a more serious note, in January 2022 a coalition of national organizations formed a front to combat misinformation and aid the campaign. In an interview, Zé Gotinha’s creator, Darlan Rosa, likewise encouraged parents to vaccinate their children. Despite Bolsonaro, a poll that month showed over 80% of Brazilian parents intended to vaccinate their children.

In 2022, Zé Gotinha returned to his original mission: educating and comforting children about vaccines. As the campaign has unfolded, he has taken to the streets of Rio with Wonder Woman and Snow White, teamed up with football mascots, and declared “Vacina Forever!” as Black Panther.

From an unnamed drawing in a 1986 vaccination campaign to internet meme, the figure of Zé Gotinha has had a remarkable trajectory. Throughout, he has remained a trusted and even beloved character for Brazilian children and adults alike. With the rise of Bolsonaro, he became enmeshed in partisan politics as part of the prolonged crisis afflicting Brazilian democracy.

Of course, the recent struggle over Zé Gotinha is a symptom rather than cause of the current crisis. Yet, the precocious droplet mascot offers us an opportunity to take stock of the present moment in light of the recent past. Zé Gotinha is, after all, only a year younger than Brazil’s contemporary democracy. More presciently, he was born as part of a series of campaigns that would cement the right to vaccination as a reliable component of Brazil’s democratic citizenship.

Bolsonaro has rattled, but not destroyed that conception. Recent polls for the October 2022 election have shown a tightened race between him and Lula. While it is impossible to predict the result, one outcome is all but certain: Zé Gotinha will persevere.

Daniel McDonald is a historian of Latin America whose research focuses on Brazil. He is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Humanities Center at the University of Rochester and will be a Lecturer in the Department of Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies at Dartmouth College starting in Fall 2022. Previously, he was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard University and received his Ph.D. in History from Brown University.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...