Cuir Mourning & Mobilization in Times of Displacement

On May 10, 2018, Bruno Alonso Avendaño Martínez disappeared in Oaxaca, Mexico, without any explanation. Bruno’s disappearance while working for the Secretary of the Navy is one more of the 40,000 disappeared in Mexico due to organized crime, femicide, and state violence. After Bruno had been missing for weeks, his brother, the performance artist and cultural anthropologist Lukas Avendaño, began to look for answers first at the Oaxaca Attorney General’s office and then in Mexico City. An impasse was reached: institutional incompetency. Negligence and the inability of governmental officials to act in an appropriate manner.

In June of 2018, the performance artist drafted a letter to Oaxaca state officials and Mexican consulate representatives in Barcelona, Spain, while the artist was doing a residency in Spain Covering twelve points, Lukas Avendaño tied their brother’s forced disappearance to the current national crisis of missing women and family members. In a trajectory to find answers and demand that their brother’s disappearance not remain unnoticed, queer artist Avendaño created a performatic intervention, Buscando a Bruno, first staged in June 2018 in front of the Mexican consulate in Barcelona, Spain (Fig.1).

Fig. 1. “Seguimos Buscando a Bruno. Por las y los Desaparecidos en México.”

I want to make a few observations on how Lukas Avendaño as performer is mobilized by the mourning of their brother’s absence. Mourning, after loss, grief, and death, has the potential to mobilize thousands, from the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, the relatives of many femicides and tra(ns)vesticides across Latin America, to those who lost beloved ones during and after the AIDS and COVID pandemics, as well as Indigenous peoples who have lost their lands. For the Zapotec/Mixtec artist from Santa Teresa, Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, mourning became a mobilizing act that became part of a constellation of mourners across the hemisphere. For the Mexican feminist philosopher Rosaura Martínez, loss and absence can create a “comunidad de duelistas” to insist on modes of reparations.

In this context, Lukas Avendaño, a muxe identified cultural producer and theorist—a queer/cuir person—enacts, along with Afro-indigenous queer poet Alan Pelaez Lopez from Oaxaca and living in the U.S., a critique of the regimes of disappearance and displacement. Both Indigenous cuir cultural producers have been affected by territorial and familial loss. Mourning, in this sense, builds to a transnational conversation between North and South. I begin here with situating muxeidad (non-normative entity) with queerness through the perspective of La utopía de la mariposa (2021), followed by an analysis of Avendaño’s Buscando a Bruno (2018). I then glance at processes of dispossession in Oaxaca that have caused displacement, migration, and mobilization. And end with Lopez’s to love and mourn in times of displacement (2020) as reflections of a diasporic experience of the Oaxaca population in the United States.

Muxeidad and Queerness

In La utopía de la mariposa (2021), directed by Miguel J. Crespo, Lukas Avendaño narrates the process of seeking answers about their brother’s disappearance while they also describe what it means to be a muxe in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. While some critics and gender theorists have claimed muxe to be a “third gender,” Avendaño describes in the video that being a muxe is more ludic and plastic, less orthodox. The muxe community is polymorphous beyond an identity than can be reduced to a “third” category. As a racialized sexuality intricately intertwined with histories of colonization, slavery, territorial dispossession, the complexity of being a muxe is synthesized as muxeidad. The performance theorist mentions that muxe can be trans, transgender, travesti, hetero-flexible and polymorpheous. Muxeidad crosses with masculinity and femininity, with power and sexual relations, with politics, and with Indigenous cosmologies and beliefs. Muxeidad is not identifiably fixed like a seed that can be picked among many other seeds, rather muxeidad is embedded with and “in collaboration” with many other seeds.

Muxe is a resignifier of mujer. Its history is not new in Oaxaca. It can be traced as early as in the encounter between Spanish settlers with Indigenous peoples. My intention here is not to trace the “origins” of muxeidad, rather to situate the complexities of its present and how racial organization, heteropatriachy, capitalism and state violence condition this minoritized sexuality. More precisely, muxeidad or being a muxe, from the perspective of Avendaño, operates a plasticity of being with one another and with the world. Avendaño has theorized muxeidad’s beingness, along with the Amaranta Gómez Regalado, Alex Orozco, Naomy Méndez, and cultural and literary agents such as Elvis Guerra. Muxeidad is in conversation with what some have elaborated as “hybridity,” “transculturation,” or a “third space.” It is polydifferential –many ways of being—and it touches on what José Esteban Muñoz describes as the Brown Commons, or lo marrón, a racialized condition of being in the world that has an emotional, affective, and corporeal effect on minorities. One of those emotional effects is mourning. A common feeling that the muxe artist performs as a disagreement of disappearances and a longing for other worldly possibilities.

Muxeidad’s resonates with queerness’ disidentifications from the dominant and normative models of being and citizenship. Queerness has gone through many transformations, from a slur, an appropriation of the term, to becoming a field of study. It has even been re-configured and defamiliarized as cuir or cuiridad, giving to some, but not to all, a gateway to explore the intersections of racialization, sexual difference, state violence and capitalistic exploitation. The debates around this term and theory coming are extensive. I want to emphasize however, how a North and South conversation through and Indigenous cuir producers makes visible the violence in the South that propel migrant currents to the North. Avendaño and Lopez situate how racialized sexual minorities extend the discussion of queer/cuir studies to comparative analyses of dispossession and displacement, where mourning appears as a triangulating point.

Buscando a Bruno (2018)

Buscando a Bruno was first performed outside the Mexican consulate in Barcelona. With the performance came a letter addressed to the Mexican representative Ernesto Herrera López. The letter named the responsible parties’ failures to give account of their brother’s absence. Avendaño called and conjured the name of Bruno. The absence of Bruno became a symbolic presence through a linguistic gesture. Outside the consulate, the artist sat in collaborative practice with members from the Xixa Theater Group. The performance was assembled with two chairs. Avendaño sat on one holding their brother’s photograph and, on the other, sat a member of the Group. Each member held Avendaño’s hand, they looked at each other, they nodded. One after another recognized their loss and disappearance. Other re-enactments of the sit-in performance were staged in front of government buildings, museums and in artistic spaces. At times, Lukas sat alone with an empty chair (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. “Empty Chair”

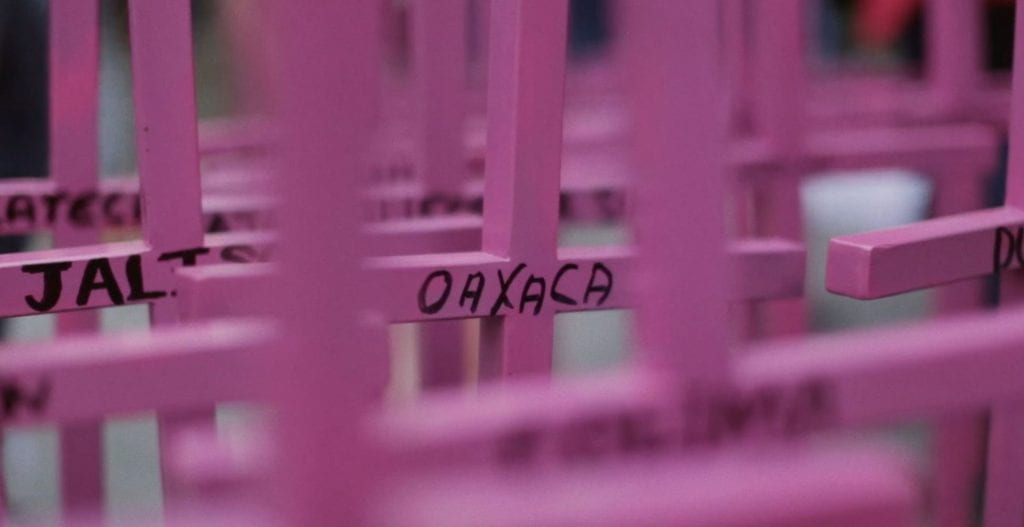

The empty seat calls for a collaborative praxis of denouncement, a void where a possible mourning subject can join, creating a community of mourners that demand answers for their absent kin. Indeed, what can connect one and many others is the feeling of having lost someone, a processual affective experience of loss that Buscando as an art form transmits to the viewer. While one of the possibilities of the performance is to fill that empty space, by Bruno, the other is to interpellate the community. Avendaño’s mourning experience does not remain in a state of melancholy, self-absorption or foreclosure from the world, rather mobilizes with many others who have seen their loved ones disappeared. In fact, in the documentary La utopía Avendaño becomes part of a greater collective of those looking for their missing mothers, daughters, wives, and siblings. From Oaxaca to Mexico City to Europe, Avendaño situates their struggle with and many others in mourning. In one of the shots, “Oaxaca” is foregrounded in an array of many (Fig. 2).

Fig 3. “Oaxaca”

In this constellation, Avendaño states that “we have the exigency to say that no one deserves to be disappeared.” Buscando a Bruno suggests that on that search and looking for ones lost loved ones, bridges across forms of loss and disappearance can be created. Territorial displacement, loss of loved ones, and an absence of infrastructural and nurturing frameworks causes many people to move, to migrate, and to seek a better life.

Disposession and Displacement in Oaxaca

Bruno’s disappearance took place in the context of the situation of Oaxaca, his home. One of the most financially disadvantaged with more Indigenous groups than any other Mexican state, Oaxaca is a vulnerable state along with those that inhabit it. Natural disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes have made visible the limits of federal aid and resources, lack of infrastructural investment, and the limit of the law that provide Indigenous peoples the right to land sovereignty. Disappearances, that of land and of people, like Bruno, hypervisibilize the failures of the state. The 2018 and 2020 earthquakes demonstrated the failures of the nation state to aid regions in the south. Yet, the people of Oaxaca found alternative organizing modes in the tequio and Guelaguetza practices to rebuild anew. Hurricane Agatha in March 2022 made apparent an absent crippling state to aid these territories. In June of 2022, I traveled to the Oaxaca coast and witnessed tremendous devastations of homes, fauna, forests, and small businesses. One local told me the process to apply for aid was difficult and, after “proving need,” he was only given 8,000 pesos (about US$500) to rebuild.

Oaxaca connects the Pacific Ocean with the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean and the Atlantic through strategic ports in Veracruz and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Such a strategic location, along with its riches of minerals has made Oaxaca a heaven for settler colonialist purchasing of lands for U.S. retirement and businesses, for foreign investment, and for excavating explorations (such as mining). Oaxaca is a contested terrain where private and foreign interests, and even local, have made people fight for their land. In the nineties, for instance, my parents had to return to the Central Valley in Oaxaca while living in Mazatlán, Sinaloa, because their land was at risk of being taken away. The way in which land rights and territorial sovereignty in Oaxaca has been disputed is very intricate, including how the Mexican Revolution, the land reforms from Cardenismo and those of Salinas de Gortari, including caciquismo and land titles play an important role. All these different factors have caused internal migration, forced migration to the North, land displacement, and disappearance. The aftermaths of these processes are reflected in Avendaño’s larger ouvre and in Lopez’s poetic interventions.

More recently, the Corredor Interoceánico del Istmo de Tehuantepec project that began in 2019 and connects the Isthmus of Oaxaca with the ports of the state of Veracruz adds to territorial displacement and deforestation, affecting the flora, fauna, and the Native communities. A project that began in 1907 by Porfirio Díaz is now being rehabilitated to create trans-Oceanic trade and movement as a “cheaper” alternative to the Panama Canal. With the corridor, there are approximately 12 cases of past and on-going projects of mining across the state including aeolian projects and politics contested by Native groups. These projects have militarized spaces, have privileged companies’ interests, and have affected Native communities. In light of the deterritorialization of the Puente Madera Community (Fig. 3), the Asamblea de los Pueblos del Istmo en Defensa de la Tierra y el Territorio (APIIDTT) was formed to counter intimidating militaristic practices and hydraulic, mining, and “modernizing” tactics. The right to defend Mixe, Mixtec, Zapotec, Ayuuk and many other groups’ lands has been at the center of the assembly, including the release of Indigenous prisoners.

Fig. 4. June 27, 2022: March against the Industrial Park of the Interoceanic Corridor

APIIDTT creates daily reports, organizes assemblies and caravans, and demands to participate in local and state law-making meetings. Territory and land for the people of Oaxaca is communal and having to lose their home would mean losing their ways of surviving. In defending their territory, land defenders have been lost, such as Samir López. The APIIDTT demands justice for Samir since 2019. Like Avendaño, whose performance emerges as a practice that mobilizes an urgency for their brother, the APIIDTT is mobilized against the regimes of power that suppress racialized forms of life. Disappearance, dispossession, and migration are, in this sense, the effects of this matrix of suppression.

Displacement due to territorial conflict, violence, modernizing projects, poverty, disasters, and lack of infrastructural support has led to migratory currents, more significantly to the United States where they have created alternative communities (for example Oaxacalifornia) and longings for an (im)possible return. These and many reasons caused my family and myself to migrate to Southern California. The experience of migrating, loving and being in “touch” with what is (temporarily) lost when crossing the borderlands is seen in Lopez’s poems.

to love and mourn in times of displacement (2020)

The poet of Oaxacan descent wrote the chapbook after visiting their mother in Massachusetts in 2017. Lopez narrates in the short introduction that while they were mourning friends, relatives, loved ones and a land they barely remembered, they were also attempting to love. The act of mourning, as the poet suggests, is constituted also on the capacity to instill a reparative motion for the self and for others. In the first poem they interrogate the reader: “ I encourage you to ask: how have I shown up for myself? And, How can I better show up for others?”

The chapbook is a dedication to others—lost and not lost—as well as a dedication to the self affected by these others. The lyricism across the poems moves from the caring of the heart, the de-romantization of an absent body, to an “open letter to femmes to often undervalued by social movements & told to mourn & love in private.” Cuir, trans, femmes, muxes, and non-normative forms of lives are foregrounded as mobilizers of action who are too often overlooked. Lukas Avendaño’s actions of justice resonate here as a “femme” cultural artist that militants for their kin. Lopez’s poetic voice tells these and many others: “I am ready to stand next to you.”

Passing through the “eighteen notes on love” for the self and for others in mourning, the poetic nature of the migrant voice hails the catastrophic dispossession and displacement of the “illegal negro.” The Blackened body that was “kidnapped by the Spanish and Dutch and shipped to Europe and then enslaved in ‘Nueva España’” is brought to the forefront to emphasize the long historical violence on racialized subjects either by slavery or colonization. Lopez tells us that they wish to write a poem, rather than an elegy for those forced out of their home and families. The poem emerges as a gesture of remembrance rethinking poetry as an archive that repairs the present and beyond. The violent deterritorialization of Black populations converses with the current displacement of Indigenous peoples in Oaxaca (the coastal regions, to be precise) that were forcibly removed from their territories.

to love and mourn in times of displacement sets mourning as a starting point for reparations. Just like Avendaño with the loss of their brother Bruno or the absence of territorial activists like Samir, or the ecocide of Indigenous lands as agroterritorial loss, the verses of Lopez’ poetry find that loss and mourning can be mobilizing. Indeed, in “mourning (v): the act of imagining and rebuilding home/family,” the poetic voice gestures on how to rebuild anew, to reconnect with familial relationships through memories, stories, and photographs. The voice talks to their kin:

“Abuela / / i was shown a photograph of your abuela / / she carries a medicine pouch on her .”

Through a photographic archive, the poem looks to rebuild a home and family. The found image refuses the disappearance of displacement kinship and Indigeneity while also restores this lost genealogy. For Lukas Avendaño, the photograph they use in Buscando a Bruno becomes part of an embodied performatic intervention that also mobilizes disagreement and justice (Fig. 1). While Lopez’s poems invite us to care and love for the self and others after loss and disappearance, for Avendaño loss is intricated with armed conflict, state violence, and land disownment. These cuir theorists and cultural producers in movement—migrating, mobilizing, and repairing— are grounded on experiential moments of mourning where mourning can be restorative and communal. The loss of kin, land, and one’s environment can be catastrophic, yet these agents—Lopez, Avendaño and the APIIDTT—endure and mobilize despite disappearance and displacement.

Jorge Sánchez Cruz is a native of the central region (Mixtec/Zapotec) of Oaxaca and Lecturer of History and Literature at Harvard University.

Related Articles

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

A Review of In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations

Merilee Grindle’s fascinating biography of Mexican-American anthropologist Zelia Nuttall (1857-1933), In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations, is a welcome sign that the field of Nutall studies is expanding.