LGBTQ+ Bars in Latin America

A Reporter’s Notebook

La Purísima is an unapologetically irreverent gay bar on Avenida República de Cuba in downtown Mexico City. One of its most endearing features is the staff who dress as Catholic priests and nuns.

I was on assignment in Mexico City for the Washington Blade, the oldest LGBTQ+ newspaper in the United States for which I am the international news editor, in July I decided to go to la Purí, as the bar’s known for short. I arrived shortly after 11 a.m. and spent the next 90 minutes or so dancing and slowly sipping shots of mezcal. I was walking outside to get some fresh air when Sergio, a staff person who was dressed as a priest, approached me in the hallway that led to the door and asked me if I wanted to go to confession. I said yes, and he led me to a small booth on the sidewalk. He unlocked the makeshift confessional and we went inside. I had learned in my childhood Confraternity of Christian Doctrine class at St. Thomas Aquinas Church that what one says inside a confessional remains between the penitent, the priest (and God.) I am not one to question Sergio’s standing within the church, but that night at la Purí was quite a memorable one.

I have reported from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Miami, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Peru, Chile and Brazil since the Blade hired me in 2012. One of the “traditions” that I have while on assignment in a particular place is to visit a gay bar. Community, regardless of place, is critically important and gay bars are a good way to interact with a certain segment of it that is privileged enough to have access to these spaces.

Some of my favorite places that I have visited while in Latin America are gay bars and clubs. They offer patrons a safe (and fun) place to be themselves, but before I list them I would like to note that not all LGBTQ+ people have access to these safe spaces.

- Bar Lou Lou is a small bar on Rua Teixeira de Melo in the heart of Rio de Janeiro’s Ipanema neighborhood. I was on assignment in Brazil twice in 2022 to cover the country’s presidential election. One night after dinner, I discovered the bar, a couple of blocks from the apartment in which I stayed while I was in Rio in March 2022.

A patron at Bar Lou Lou in Rio de Janeiro on March 18, 2022 (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

I saw Pride flags and a group of people standing outside on the sidewalk. Walking inside, I ordered a caipirinha and soaked up the lively atmosphere. I returned to the bar a couple of days after. It was my last night in Rio before I flew back to D.C. A Brazilian volleyball player introduced himself to me and invited me to hang out with a group of people from the United States, France and the United Kingdom. whom he had just met. I speak limited Portuguese and his English was limited, but the language barrier did not matter to me and to the group of friends we had just made. We danced and drank caipirinhas for several hours inside the bar and on the sidewalk until closing time at midnight. We exchanged phone numbers and Instagram handles before we hugged each other and said goodbye. I remain in touch with several of them today.

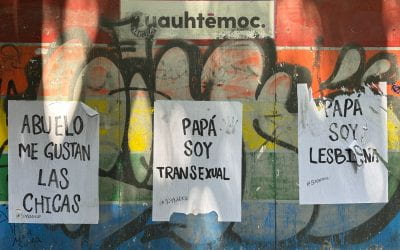

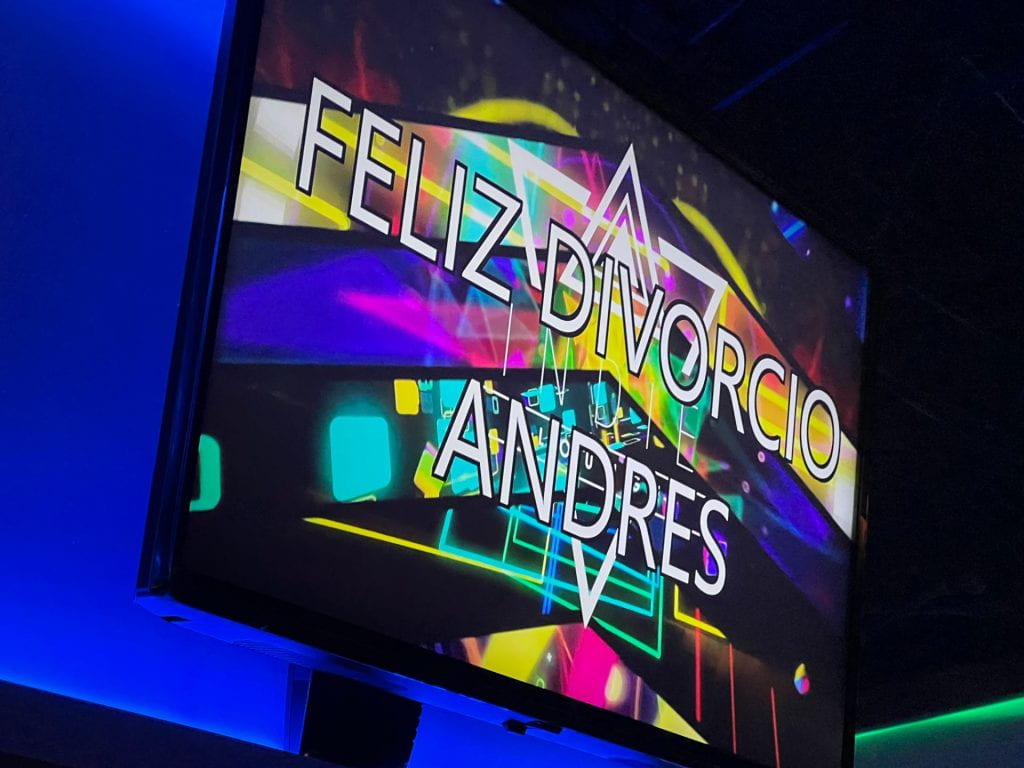

- Indie Lounge is a gay bar in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, that I visited on Feb. 9, 2022, while I was on assignment in the country. Vice President Kamala Harris and U.S. Agency for International Development Administrator Samantha Power had attended Honduran President Xiomara Castro’s inauguration a few weeks earlier. I was driving to an interview with Victor Grajeda, the first openly gay man elected to the Honduran Congress, in San Pedro Sula, two days earlier when I heard on the radio the U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced sanctions against former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández for corruption. (Honduran authorities on Feb. 15, 2022, arrested Hernández at his Tegucigalpa home after the United States requested his extradition on drug trafficking and weapons charges. Hernández’s brother, former Congressman Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, is serving a life sentence in the United States after a federal jury convicted him of trafficking tons of cocaine into the country.) On the night I visited, Indie Lounge staff invited patrons to submit messages that would then appear on television screens throughout the bar. One of the messages read, ‘happy divorce, Andrés.” My husband’s name is Andrés, and I began to laugh when I saw it.

Indie Lounge in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, on Feb. 9, 2022. (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

- Las Tunas, Cuba, is a provincial capital about 400 miles southeast of Havana. The National Center for Sexual Education (CENESEX), a group directed by Mariela Castro, the daughter of former Cuban President Raúl Castro, organized a series of events in the city in May 2015 to commemorate the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia (IDAHOBiT), which honors the World Health Organization’s decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder on May 17, 1990.

The bone-jarring drive from Havana to Las Tunas took more than 10 hours, and I finally arrived in the city shortly before 1 a.m. on May 16. The IDAHOBiT march that Mariela Castro led took place a few hours later. She and two activists later paid homage to Vicente García, a leading figure in the 10 Years’ War from 1868-1878 during which Cubans fought for independence from Spain, during a ceremony that took place in Las Tunas’ main square.

CENESEX also organized a party at a local nightclub on the city’s outskirts. It was around 2:30 a.m. on May 17 when a local bus driver introduced himself to me and asked if I wanted to go to the “after party.” I was exhausted, but I nevertheless accepted the invitation. I had never been to Cuba before, and I took him at his word when he told me that we would take a taxi to the restaurant where the party was taking place. We walked outside and climbed into a horse-drawn cart that brought us, his friends and a drag queen to the party. Our boisterous group made jokes and laughed at each other as the cart made its way through the city. The trip took less than 15 minutes, and the party continued once we arrived at the restaurant. Dawn was breaking when I returned to my hotel. I rested for a couple of hours and then began the long drive back to Havana. (I had reported from Cuba several more times when I arrived at Havana’s José Martí International Airport on May 8, 2019. Cuban customs officials told me that my name was “on a list” and they would not allow me into the country. I spent the next seven hours at the airport before an agent escorted me onto a flight back to Miami. The Cuban government has still not provided me with an official explanation of their decision not to allow me into the country. A contact suggested Mariela Castro, who is a member of the Cuban National Assembly, told the government not to allow me into the country because she did not want me to cover an LGBTQ+ rights march that independent activists organized in Havana three days later. The Cuban government has, to my knowledge, never publicly disclosed why it decided to prevent me from entering the country. I explained what happened to a press attaché at the Cuban Embassy in Washington me in July 2021 after he emailed me about meeting for coffee. He clearly did not know what his government had done to me. I did not hear back from him after I told him what happened.

- Mexicali is a Mexican border city that borders Calexico, Calif., in the Imperial Valley. I was on assignment in the area in July 2018.

The temperature was well over 100°F when I parked my rental car in a parking lot in Calexico at shortly after 8 p.m. on July 21, walked to the border crossing and entered Mexicali. I had a couple of tacos at a small, family-run restaurant and then walked to Taurinos Bar, a gay bar a few blocks south of the border. Patrons were playing pool and drinking beers while I asked the manager about then-U.S. President Donald Trump’s immigration policies and their impact on LGBTQ+ people. I finished the interview and then walked to Porky’s Divine, another gay bar three blocks south of the border. A California woman and members of her bachelorette party were among those who were inside when go go boys took the stage. A drag queen dressed as Frida Kahlo was among those who also performed. The temperate was still around 100°F when I left Porky’s Divine shortly after 1 a.m. on July 22. I stopped at a nearby convenience store to buy a bottle of water and a bag of potato chips before I walked back through the border crossing and into California. I was back at my hotel in El Centro, roughly 12 miles away, in less than half an hour.

A drag queen dressed as Frida Kahlo at Porky’s Divine in Mexicali, Mexico, on July 22, 2018. (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

Not everyone can access these spaces: They often have cover charges, and that cost, along with drinks and transportation to/from them, are prohibitive to someone who is not economically privileged. And this economic privilege often goes hand-in-hand with violence and discrimination based on factors that include sexual orientation, gender identity and race.

“Access to a car or a job that does not involve sex work could very well mean the difference between life and death for a trans Salvadoran woman or a gay man who is perceived to be too effeminate,” I wrote in the Blade on Feb. 7, 2017, after my first reporting trip to El Salvador. “Many of these people feel as though they have no other option than to leave the country and migrate to the U.S.”

Alexa, a transgender woman with whom I spoke for the Blade in La Ceiba, Honduras, on July 20, 2021, told me it is “very difficult to lead the lifestyle that we lead as trans women” in the country because of discrimination and a lack of employment opportunities because of her gender identity. Alexa spent nearly three years in prison after authorities charged her with attempted murder, even though she claimed she was defending herself against a woman who was hitting her in the face with a rock.

She told me a Salvadoran man raped her in prison. Alexa also said the warden forced her to cut her hair and guards doused her with cold water in an isolation cell after the attack.

“I was a woman,” said Alexa. “They made me a man.”

We were both crying during the interview. We embraced each other for several minutes when it was done.

These stories are incredibly difficult to hear, and they are indicative of the reality for many LGBTQ+ people in the region who struggle to survive on a daily basis. It is crucially important to share these stories. It is also equally as important to show our readers there are safe spaces in Latin America that offer LGBTQ+ people a safe place where they can be themselves. Bars and clubs such venues.

Theatrón in Bogotá, Colombia, on Sept. 19, 2021. (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

Michael K. Lavers is the International News Editor for the Washington Blade, the oldest LGBTQ+ newspaper in the United States. He has reported extensively throughout Central and South America and the Caribbean. Michael lives in D.C. with his husband.

Related Articles

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

A Review of In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations

Merilee Grindle’s fascinating biography of Mexican-American anthropologist Zelia Nuttall (1857-1933), In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations, is a welcome sign that the field of Nutall studies is expanding.