Learning about Cuba’s LGBTQ+ Community

The Genesis of a Book

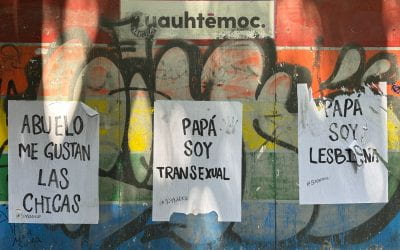

People with signs during La Conga en contra de la Homofobia y Transfobia in La Habana, Cuba, May 2023

Cuba’s held a fascination for me ever since I was in high school in Puerto Rico. I explored the food, music and art of the neighboring island, quite abundant in my homeland, but always knew that different perspectives and adventures could only be experienced in Cuba itself. I never imagined that 15 years later, I would be able to visit, conduct research for my doctoral dissertation in Social Work at Simmons University, and develop lifelong friendships.

My book, The LGBT Cuban Revolution (Deletrea 2023), emerges from my research, visits to Cuba and personal experiences, examining the LGBTQ+ movement in Cuba since the beginning of the Castro-led Revolution. I was curious about how this type of government and revolution affected the LGBTQ+ community. I wanted to focus solely on the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community living in Cuba, hence I only included the perspectives of those “who stayed.” Many, if not all, previous books and projects have dealt with homosexuality in secondary data analysis interviews or with people who fled Cuba.

I interviewed Cubans on the island who described their personal histories and how the 60-plus years of the Cuban Revolution have affected their LGBTQ+ identities and their coming-out processes, as well as about their experiences with the traditional Latino social and cultural norms about gender and sexuality. Their stories helped me understand the special nature of this community, which is separated from the United States due to the embargo imposed by the United States and because its political socialist/communist ideologies shouldn’t allow for the openness of the LGBTQ+ community to even exist.

I am a gay Puerto Rican man, born and raised in San Juan. My uncle was the first person to teach me about Cuba in his apartment in Old San Juan. He had books by José Martí and many other writers from Cuba and Puerto Rico. I read and viewed the pictures while he looked after me. I considered him the family’s filósofo (philosopher) and scholar (and still do), and I admire him for it.

In high school, I participated in Model United Nations competitions, and that’s when I first read about the Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro in 1959. I read about Cienfuegos, Ché, Vilma and other revolutionary figures. After graduating high school and moving to Massachusetts to go to Boston University, I wanted to visit Cuba to learn first-hand about its LGBTQ+ community. Up until then, I could only read about peoples’ perspectives from the United States. I couldn’t read the news from Cuba directly until I met two professors, Susan Eckstein and the late David Scott Palmer, who provided me with Cuban books, articles and newspapers. I couldn’t wait for the day I could go there. I wanted to meet Vilma Espín and Mariela Castro-Espín, now the director of the Centro Nacional para la Educación Sexual (National Center for Sexual Education, or CENESEX for short in Spanish), Ramón Silverio from the El Mejunje Cultural Center and the guiding lights of the LGBTQ+ community. I wanted to talk to LGBTQ+ people throughout the country.

Many opportunities came and went; plane tickets were too expensive, my visa was denied, or I couldn’t make the dates. But the day finally arrived. It was early 2000. I had submitted a proposal to an international conference in Havana, Cuba. My proposal got approved, and I couldn’t believe it! It was my first time flying to Cuba and presenting at an international conference. I asked so many people for details about their experiences visiting the island. My friend Oz Mondejar, whom I consider “my Cuban brother that I never had,” connected me with his family and friends living in Cuba. My plane touched down at the airport and I had a fantastic trip, the first of many more to come.

By 2014, I had traveled to Cuba to research, study and teach at the Universidad de la Habana, as well as to lead humanitarian efforts, meet members of the LGBTQ+ community and join the annual Conga march against LGBTQ+-phobia.

Mariela Castro Espin and author Wilfred Labiosa, leading the Conga en contra de la Homofobia y transphobia in La Habana, May 2019

I learned about the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community, its peculiarities, culture and beliefs. Those living in Cuba have faced and continue to face challenges. Gay and transgender people were ostracized before and during the Fidel Castro-led Revolution in 1959 and persecuted as deviants. Engaging in homosexual behavior was illegal and punishable under Cuban law until late 90’s. Gays and lesbians have been punished in the past for not dressing the part expected by society, using specific mannerisms or working in the “wrong” field such as sex work. Legal cases and newspaper articles referred to LGBTQ+ individuals as deviant homosexuals who could be killed or mistreated by authorities[1]. LGBTQ+ people who came out of the closet were considered unproductive members of society who displayed behaviors contrary to Latino cultural norms.

Many homosexuals were imprisoned or killed during the first years of the Cuban Revolution, from 1959 to 1961, for allegedly opposing the Revolution. At that time, all citizens were expected to contribute to the Revolution somehow. However sex workers, homosexuals and religious leaders were not considered productive members of the Revolution and were thus singled out for prosecution. Those suspected of such behavior were arrested and imprisoned. In these historical circumstances, the processes of coming out and self-acceptance of Cuban LGBTQ+ people were most likely influenced by criminal laws and social culture, as people were expected not to express any differences in ideologies, personalities or views. Everyone had to conform. This new social and cultural norm of homogeneity did not eliminate historical taboos and assumptions about women’s and men’s gender roles in Latino culture. Machismo and marianismo reflect the complexities of male and female roles in the Latino culture; these are instilled in Cubans from birth and integrated into their being.

I spoke with many Cubans during humanitarian trips distributing aid to provinces. During these trips, LGBTQ+ folk always approached to say hello and began to “open” up about their stories. One of these interactions happened in a small town outside of Santa Clara. My group was distributing books, school supplies and medications; a young man approached and asked if I could give him my backpack to use in the university. I saw it and realized that it had the pride flag printed on it. I asked him, “Do you know the meaning of it?” He answered, “Si, soy de la familia” — he and I were in the “LGBTQ+-family.” I gave him the backpack and asked about his story. He began to relay a story of challenges and traumas, including his coming-out story. I heard similar stories with such frequency that I decided to record them.

When it was time to work on my dissertation, I choose the topic and began to document LGBTQ+ stories in Cuba in a formal manner, conducting my research over a period of 11 months in Spanish. Forty-seven LGBTQ+ subjects were interviewed formally. The sample was found through a snowball method based on word-of-mouth and attendance at LGBTQ+-focused events and social gatherings nationwide. I conducted interviews in 12 of Cuba’s 15 provinces, although I concentrated on La Habana, Cienfuegos, Villa Clara and Sancti Spiritus. This sample was created using the saturation concept as a guide. Once all of the categories and themes mentioned during this process[2] were repeated, data collection was halted.

My book contains my experiences and those of people I met in Cuba. Each chapter is organized around a theme or topic representing a historical event that shaped the current LGBTQ+ movement in Cuba, and includes quotes from the interviews describing the historical moment that marked the Cuban LGBTQ+ movement.

My experiences in Cuba have impacted my life— especially visiting provinces and meeting my “brothers and sisters.” Surprisingly enough people were so open to talk to me freely about their experiences, the good and the bad. Individuals, even today, remember those interactions with me; even some of them, in their wills, have left for me mementos of their time in the UMAPs (Military Units to Aid Production, where gays were forced to labor), art works, videos and so many other things that meant so much to them. It moves me to receive letters, left for me with the memento. I will treasure this experience and research forever.

As a Puerto Rican gay man, I was surprised about Cubans’ openness even though they live in such a different nation than mine. An academic advisor once observed that it was because I had developed a relationship with my interviewees; yes, most probably but I think it is because we saw each other as individuals struggling to survive in a machista, sexist and LGBTQ+-phobic world. Although I am Puerto Rican, and they are Cuban, we both understood that our LGBTQ+-lives were impacted by colonialism and all the -isms of our society, especially intolerance towards us and the pressure to conform.

Using a queer theorist perspective, I would say that Cuba’s LGBTQ+ community is an excellent example of a community that is neither fixed nor has a vertical entity that can only be used in one way, nor is it isolated or hierarchical. Instead, it is a web of relationships, discourses, practices and institutions that span all social spaces and subjects [Huffer, Lynne,Mad for Foucault: Rethinking the Foundations of Queer Theory. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010)]. After years of struggles, fights and community organizing, the LGBTQ+ community has been integrated into the fabric of Cuban society, culture, santería, government, commerce and politics. The current processes of inclusion and acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals have provided collective rights and power in the workforce, business entrepreneurship, government and culture.

Pride Celebration in Santa Clara, Villa Clara, Cuba, in front of El Mejunje de Silverio (first cultural establishment approved by government to be a gathering space for the LGBTQ+ community, May 2017

The changes to LGBTQ+ life in Cuba are happening throughout the whole country at a steady and fast pace. Cuba’s LGBTQ+ community experienced the sexual transgressions common in a totalitarian regime, but these are now fading from Cuban society and transforming into acceptance and empowerment for the community. The diversity of the LGBTQ+ community is visible and palpable in Cuba today. I would argue that, ironically, the persecution of gay Cubans allowed for the formalization of the movement and the meeting of others within the LGBTQ+ community.

The effects of the Revolution will be long-lasting and ongoing, but they have influenced and assisted in the development of a LGBTQ+ movement of today. The LGBTQ+ individuals I have met are passionate about their country.

Most surprising is that throughout the years I can see and feel the changes for the LGBTQ+ community. The current generations of LGBTQ+ Cubans can find a lively community with services, bars and restaurants, hotels and sites that reach out to them and hang the Pride flag on their premises. Equal marriage and same-sex adoptions are the law and all government Cuban codes or laws are inclusive of the LGBTQ+ community. Today, I feel more free and safe in Cuba than in my own native Puerto Rico. Ashe pa’ usted!

Wilfred W. Labiosa, Ph.D., is a community and non-profit leader, advocate and mental health care provider, for the last thirty years working in the public health field with marginalized communities such as the Latino and LGBTQ+ communities. He has taught in various universities in Massachusetts, and has participated in Harvard Medical School Addictions symposium . He is currently the CEO of Waves Ahead Corp, a non-profit organization in Puerto Rico whose main objective is to support the development and transformation of LGBTQ+ communities, specifically LGBTQ+ seniors and homeless, www.wavesahead.org.

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.