EsCultura Queer

Sculpting A Pride March of Memories Across the Continent

On June 11, 2016, hundreds of LGBTQ+ Floridians danced the night away at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando. Because it was Latin Night, the crowd probably heard various songs from Shakira, Thalia or Ricky Martin. As is the case with plenty of other Latin Nights at other LGBTQ+ clubs I’ve been to, there’s no doubt everyone loudly sang in unison to Selena’s “Como la Flor” at around midnight. I’m guessing drag performers took the stage at some point to entertain the crowd with some iconic songs by Celia Cruz and Gloria Trevi. In reality, I don’t know exactly what songs were played or what the crowd was like that night. What I am certain about, however, is that at around 2:30 AM, LGBTQ+ communities from across the globe felt a collective heartbreak. At that moment, 49 of our siblings, most of whom were Latinx, lost their lives in one of the deadliest mass shootings in U.S. history.

Until recently, that pain—forever seared within our chests—was strictly somatic. Our memories of the victims were enshrined in the anxiety that runs through our veins whenever we hold a partner’s hand in public. We’re reminded of that tragedy every time we timidly dance around pronouns or nervously decipher if a new acquaintance is open minded enough for us to live authentically around them. For years, their lives were only memorialized in agony. Fortunately, that will soon change; the Pulse night club will become a permanent national memorial and museum, one that will celebrate the lives of those 49 souls and raise awareness of LGBTQ+ movements throughout history. Finally, we will no longer have to skip a beat in order to think about what happened as this new monument will embody what happened at Pulse, allowing us to heal as a community and reflect on this difficult path as we move forward to a brighter future.

I reflect on the significance of this monument—to memorialize those we lost, to raise awareness of LGBTQ+ histories, and to instill a sense of pride to prevent such tragedies in the future. And I can’t help but think: what other monuments like this one exist? How else can we learn about LGBTQ+ communities, especially QTBIPOC—queer and transgender, Black, Indigenous and people of color? Are there displays born solely out of pride, rather than tragedy? Motivated by these musings, I did quite a bit of digging around to find more of these monuments, and I specifically looked at the region that helped me feel the most affirmed about my sexuality and identity: Latin America.

Photo courtesy of https://www.noticel.com/lgbtt/ahora/la-calle/20160626/inauguran-primer-monumento-a-la-lucha-gay-en-puerto-rico-galeria/

My investigation first took me to San Juan, Puerto Rico, home to two monuments commemorating the LGBTQ+ community. Within two weeks of the tragedy at Pulse, the city erected seven colorful pillars in the Parque del Tercer Milenio to honor LGBTQ+ social movements. Though this project was already in the works before the Pulse massacre, a plaque was also added to the design to name the 49 victims—23 of them were of Puerto Rican heritage. Not far from the park, in the Dársenas Plaza in old San Juan, sits the Pórtico de la Igualdad. Built in 2019, the seven panels—each a different color of the rainbow—share words like Amor, Libertad and Respeto to recognize the 50-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, a series of spontaneous demonstrations by the LGBTQ+ community in response to a police raid of a New York gay bar. There are also talks of building a statue to honor the life of Alexa Negrón Luciano, an unhoused transwoman who was murdered in 2020. Currently, photos, candles and messages from her vigil remain in a park in Toa Baja to serve as a temporary memorial.

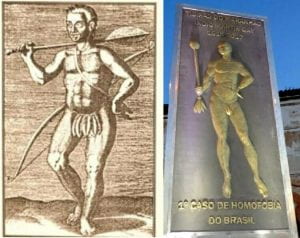

Heading southwards, I found that in Brazil, the city of São Luis, Maranhão raised a life-sized statue of Tibira, an intersex Native American who was executed by French missionaries in 1614 simply for engaging in sexual activity. A member of the Tuipinambá Indigenous community, Tibira is known as the first Indigenous martyr of Brazil who was slain for their sexual and gender identities. Tibira’s legacy is now immortalized in the region where they lived more than 400 years ago. Their monument includes the words “Primeiro Caso de Homofobia do Brasil” as a reference to the introduction of trans-antagonism and queer-antagonism to the land through European colonization. Tibira appears to be the only LGBTQ+ Native American within Latin America to have a statue commemorating their martyrdom, though many more of these martyrs exist. Nearly a century before Tibira’s murder, Spanish colonizer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa ordered the execution of at least forty two-spirit individuals of the Quarequa tribe in present-day Panama. Balboa not only has a statue in Panama City overlooking the Panama Bay, but has been honored with an entire park in San Diego, CA. Hopefully, modern movements that led to Tibira’s statue can influence the replacement of Balboa’s in Panama with one honoring those two-spirit Quarequa martyrs.

Photo courtesy of https://www.hypeness.com.br/2019/04/indio-tupinamba-morto-em-1614-foi-primeira-vitima-de-homofobia-registrada-no-brasil/

Moving further south to Río de Janeiro, a statue will soon be displayed to recognize the accomplishments of Marta Vieira da Silva, one of the world’s greatest athletes. Vieira da Silva, who has fought for women’s soccer all her life and who holds the record for most goals scored in World Cup history (men’s or women’s), recently helped the Brazilian women’s team achieve equal pay. Recently engaged to her Orlando Pride teammate Toni Pressley, she will be one of the first out athletes in the world to have a statue, and hers will stand proudly next to Pelé, another Brazilian soccer legend.

To the west in Buenos Aires, Argentina, LGBTQ+ rights and HIV/AIDS awareness activist Carlos Jáuregui was honored with a subway station in 2017. The metro stop is adorned with informative plaques detailing his contributions, including forming Gays and Lesbians for Civil Rights in 1991 and organizing the city’s first pride march in 1992. In addition to his mural are rainbow stairs and a series of other art projects celebrating other members of the LGBTQ+ community. Throughout his life, Jáuregui was very vocal about cis-gay men showing up for the rest of the rest of the LGBTQ+ community. He felt that the movement needed to be intersectional and do a better job of centering lesbian, bisexual and transgender voices.

Photo courtesy of https://www.clarin.com/ciudades/estacion-subte-lleva-nombre-carlos-jauregui_0_ryEIpSpog.html

In nearby Montevideo, Uruguay, LGBTQ+ communities are proud to have a plaza of their own: la Plaza de la Diversidad Sexual. Established in 2004, this public area was created after activist groups fought for its creation, and the municipal government gave its unanimous support. In the center, the plaza features a triangular monolith—a reference to the symbol used in concentration camps—with a message calling for visitors to honor diversity, including respecting all genders, identities and sexual orientations. A local treasure, the plaza is not the only one of its kind; in 2018, the city of Buenos Aires opened one, too. Complete with fountains, rainbow-colored walls, and various displays of art, the plaza is a monument that also exists to educate the general public. All over the park, visitors can read one of their signs to learn about pronouns, local LGBTQ+ history, or other relevant topics.

Heading north, across Mexico are various monuments dedicated to Frida Kahlo, the famous artist from the Coyoacán neighborhood of the nation’s capital. Frida, who was very open about her sexuality throughout her life, is a national icon whose artwork is celebrated all over the world. Her house, La Casa Azul, is a national museum, and a short walk away is a statue of her with her husband Diego Rivera. Frida’s likeness is also visible on the 500-peso bill, and she is not the only queer woman featured on the nation’s currency; another is Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a lesbian poet, author and nun born in 1648 in the then-pueblo of Tepetlixpa, not far from what is now Mexico City. Sor Juana was an ardent feminist who wrote in Nahuatl and was known for presenting as a man in order to enter academic spaces. However, it is worth noting that Frida has a long legacy of appropriating aspects of Tehuana culture, and Sor Juana owned enslaved people. As is the case in the United States, similar conversations about which individuals we should immortalize in monuments are taking place south of the border as well. Mexican activists and progressives, among others in Latin America, are rethinking the legacy of these queer historical figures, and rightfully so.

Also in Coyoacán is a statue of Salvador Novo, a gay poet, journalist, radio personality and playwright who, in the 1930s, wrote various stories featuring queer and trans characters. In addition to his statute, the street where his childhood home sits was also named after him. Moreover, within Mexico City, there are plans to recognize lesbian ranchera singer Chavela Vargas. Originally born in Costa Rica, Vargas was well-known for her embrace of her sexuality and butch aesthetic, as well as her relationship with Frida. Lastly, Juan Gabriel, the famous singer who passed away in 2017, has monuments in Monterrey, Mexico City, Juárez, Tijuana, and even in a new bar in Los Angeles, among many other places in the Western hemisphere. JuanGa, as he was affectionately known among his fans, regularly played with his gender expression, often dressing in bright pink ties and sparkly, purple coats.

Stateside, I was fortunate to find a handful of other Latinx-centered LGBTQ+ monuments as well. In Los Angeles, California, The Wall-Las Memorias commemorates the thousands of lives lost during the ongoing AIDS epidemic. HIV and AIDS still disproportionately affect communities of color, including all over Latin America, which is why the artists consider it a living monument. Designed as Quetzalcoatl, a feathered serpent from various Mesoamerican traditions, the monument coils into an arch in the center of Lincoln Park, and eight wall panels surround it, six of which feature murals of AIDS in LGBTQ+ Latinx communities and two listing the names of individuals who have passed as a result of AIDS complications. Across the country in New York City, She Built NYC will soon unveil a statue to honor Sylvia Rivera, a trans Puerto Rican activist who, along with her best friend Marsha P. Johnson (who will also be getting a statue) and Stormé DeLarverie, started the revolt at Stonewall back in 1969.

These seem to be the only existing or planned monuments that commemorate LGBTQ+ communities of Latin American heritage. However, there are various public spaces all across the region that have been reclaimed as LGBTQ+-affirming. In Cuba, for example, artist and journalist Victor Hugo Robles, better known as el Che de los Gays, decorated a statue of revolutionary José Martí with red lipstick and a rainbow scarf. Robles used this opportunity to critique the corporatization of pride as well as the pink-washing that occurs in many western powers, specifically referring to advancing LGBTQ+ rights in their regions as a means of hiding inhumane laws and practices. He also chose Martí, in particular, given his legacy of homophobia. Shortly before his death, Fidel Castro went on to apologize for the various queer-antagonistic and trans-antagonistic actions taken throughout the Cuban revolution. According to Robles, leftist movements need to reckon with their previous belief systems, and he has engaged in various other public displays in his native Chile, where he is known for his critiques of neoliberalism and the country’s painful dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet.

Photo courtesy of http://mujerescreando.org/nuestros-suenos-no-caben-en-sus-urnas-la-plaza-de-la-chola-globalizada/

Similarly, in La Paz, Bolivia, Mujeres Creando, an anarcha-feminist collective, unites the nation’s Indigenous peoples through anti-capitalist gatherings that bring together disparate interest groups. Late last year, they transformed a statue of Isabel I of Castille, who supported Christopher Columbus’s conquest, and reclaimed the public square as La Plaza de la Chola Globalizada. Organizers dressed her with local attire as well as a trans flag and various signs reclaiming her as a chola, or an Andean woman. In doing so, they challenged neocolonial notions around femininity, gender, beauty and sexuality.

In more subtle ways, monuments across Latin America also exist among insiders of the LGBTQ+ community to demarcate safe spaces. Jamaica’s gullies are a known place for transwomen to gather. The Peruvian neighborhood of Miraflores in Lima is home to various queer nightclubs, and the famous Parque Kennedy with its statue of John F. Kennedy in the district’s center is an area where many queer and trans people socialize during the day. An abandoned military bunker outside of Havana—an inadvertent monument—is a space for queer men, especially Black Cubans who have been marginalized by the larger LGBTQ+ movement, to socialize in safety. In El Salvador, the plaza housing the monument El Salvador del Mundo in the nation’s capital is another space for LGBTQ+ groups to unite, and it is also the spot where the annual pride parade begins. Mexico City’s Ángel de la Independencia, a victory column landmark, marks the beginning of the famous Zona Rosa, the capital’s hub of LGBTQ+ culture and nightlife.

Ultimately, Latin America is home to a growing number of monuments recognizing LGBTQ+ communities. I’ll admit, when I first began my investigation, I was worried that I would not find many monuments to share; they are few and far between in the United States, and I mistakenly used that as a barometer for the rest of the hemisphere. However, now I can honestly say that my research affirmed my own sense of pride about my sexuality and ethnic heritage. I am inspired by existing and future monuments as well as the reclaimed public spaces that advance LGBTQ+ social movements, and I have even more hope that increased visibility within the region will continue to encourage more Latinxs of different gender identities and sexualities to live authentically as themselves.

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Michael Vázquez is a second-year Ph.D. student in Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. His research explores the intersections of ethnic-racial identity, gender, and sexuality, among other aspects. He is an active member of the Latinx Student Association and LGBTQ@GSAS, often planning events that combine both of these parts that make him whole.

Related Articles

My cry into the world

English + Español

It was September 20, 2019. “One hundred, two hundred, three hundred, four hundred….” That was how we felt and that was how we counted in the face of the irremediable absences provoked…

When Decolonization Meets an Immovable Monument

It was early October 2013, well before the present wave of toppling statues in the name of decolonization gained momentum in the United States and the United Kingdom…

The Ghosts of Canudos: A War Memorial

English + Español

Just like in the Argentine pampas or in the plains of Venezuela, the space in the Brazilian sertão, in the country’s Northeast region, has no limits. The hard brown land seems to stretch out in all directions, undulating endlessly, and the feeling it provokes is inevitably one of melancholy