Family Roots in the Brazilian Countryside

A Story of Departures and Returns

Warm tears dropped on my lap as I hopelessly stared at the cows in the pasture. Nobody had told me so, but—as my dad drove us away—I knew that was the last time I would contemplate that landscape. The year was 2005 and neither my dad nor aunt considered taking over the farm’s operations, in the countryside of São Paulo state, after my grandfather, Rafael Mazza, passed away.

São Paulo state is located in the southeast of Brazil (Wikipedia map)

For one, it was a four-hour drive to the capital, where we lived and where I could go to a good school and my mom, our primary provider, could work as an office secretary. Then, managing any farm, even a small one, is a lot of work: attending to the crops and animals, managing the cash flow, selling and delivering the produce. To make matters worse, the farm had never been profitable: not the cow’s milking parlor, nor the laying chickens, nor the crop fields, nor the fruit trees. It was what they called a “hobby farm.”

The land, acquired in the 1950s with the inheritance money from my Italian great-grandmother, Maria Rosa Muraca, was small even for local standards—something like 60 acres of mostly pasture for cows to graze on. Other farms in the region were slightly larger, but all of heterogeneous sizes and shapes. In that region, most rural properties were family-owned and employee-operated, focused on milk production that was sold to a local cooperative.

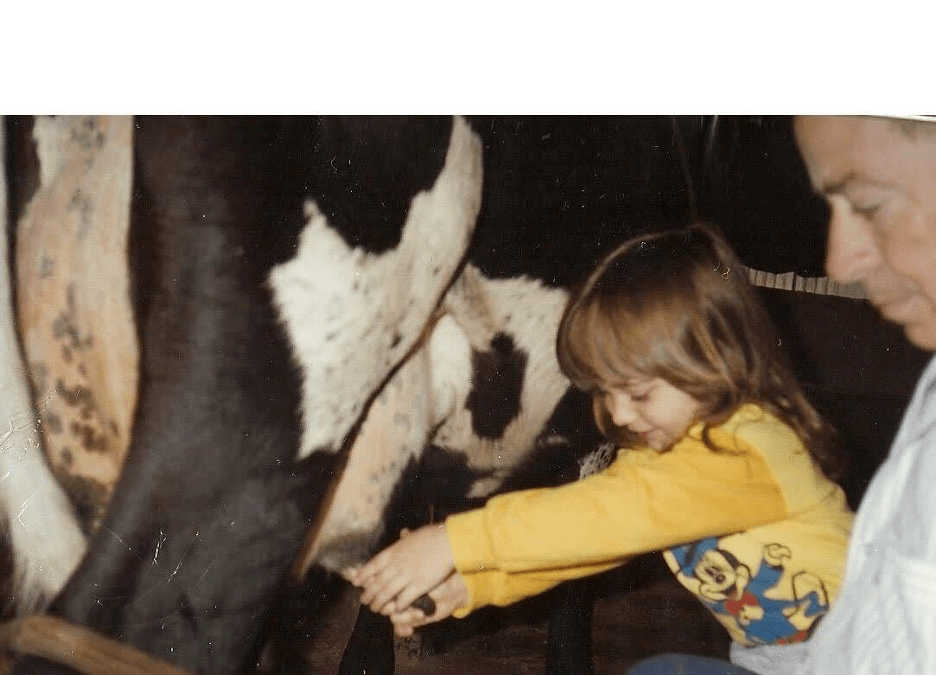

Rafaella trying to milk a cow with her grandfather Rafael.

Looking back, I think my grandpa never saw the farm as a business and that is why he never bothered too much about making it profitable nor putting a transition plan in place for us to inherit the land and its activities. Instead, he subsidized the farm operation with the profits he got from his car repair shop in the city. That land was his retreat, his safe haven—and ours too; he called it Sitio Grama Verde—the Green Grass Small Farm. And, for our family, Sitio Grama Verde felt gray and like a ghost town with him no longer around. There was no detaching the notion of him from the notion of that place.

As personal as this story is for me, it is far from being an isolated phenomenon. According to a survey study, “Governance and equity management for agribusiness families in Brazil,” more than four out of every five of the country’s farms are led by either first- or second-generation farmers. Only 16% are managed by the third generation—and less than 1% is currently operated by the fourth generation. This is a startling statistic, especially when compared to the usual Midwest multi-generational farm operations in the United States, for instance.

These numbers indicate an underlying problem: younger generations are not taking over their family farm operations but moving to urban centers instead—where they go to study and work, and almost never to return. This populational movement, from rural areas to urban ones, is called a rural exodus— “êxodo rural.” According to a study published in 1999 by IPEA – Instituto de Pesquisa Economica Aplicada, “rural-urban migration has been responsible for the reduction of rural population. At a national level, this reduction has continued over the last 50 years. During 1950/80, most of the national rural urban areas was originated in the southeast and the south regions.”

The study goes on to explain that, in the 50s, four million people—or 30% of the rural population of São Paulo state at that time—moved to urban centers in the state. In the 60s, that number was six million people—or 46% of the rural population of the state. These numbers have declined since the 70s but, according to IBGE, by 2010 less than 5% of the state population—or fewer than two million people – still lived in rural areas.

Many other Brazilian families started from a similar place as my own: Italian immigrants who had to leave their homeland to flee starvation or World War I and came to Brazil looking for better life opportunities. Public policies at the time placed this foreign labor on coffee plantations. Fast forward a century and most of these families ended up leaving farming for city jobs.

There are several reasons why younger generations decide to stay or leave their family farm operations. In 2018, IPEA published another study analyzing the problems and challenges of succession (the process by which a farm or business is handed over to the next generation). It finds that producers will remain in the agricultural activity only if they earn enough.

Historically, the main challenges to stable earnings have been high volatility in commodity markets, rising labor and land costs, financial and operational risks. On top of that, farm mechanization, job opportunities in urban centers, new consumption habits and conflicting family dynamics all contributed to historical migratory movements.

Personally, I don`t believe migratory movements, when they are not forced or caused by disasters (which unfortunately is likely to become more frequent because of extreme climate events), are all bad. I probably would never have had my career and academic opportunities—let alone attended Harvard—if I hadn’t grown up in the capital, per example.

From a national economy perspective, technological advancements such as farm mechanization have been a major factor to unlock the country`s agricultural production potential and establish itself as a food production global leader. Over the past 30 years, Brazil’s planted area has doubled; but, because of better productivity (output per area), the total production has increased more than five times. As much as mechanization has changed the need for manual rural labor, it did not completely substituted it: while the number of tractors has increased fivefold in the past 40 years, the number of farm labor jobs has not fallen proportionally (it decreased 25%).

Other than the usual historical factors, extreme weather events caused by climate change are likely to become a leading factor for forced migration flows inside Brazil—for example, the heavy rains and floods in the Amazon and Rio de la Plata basins in 2019 triggered more than 237,000 new displacements in Brazil. This number more than tripled in 2022 due mostly to floods. I would also expect that the statistics for 2023 will show the impact of recent severe droughts in the Amazon, affecting over 500,000 people in the northern region of the country.

On the other hand, if we look at the factors that play in favor of one’s deciding to stay in their family farm, we could list the local knowledge of soil and climate, as well as experience accumulated over years and generations managing crops and livestock on a certain piece of land. Public policies, educational programs, and fiscal, debt or tax incentives are all initiatives that can help individuals stay in rural areas.

Nonetheless, in many countries, because many small farms can’t generate enough income to sustain a family, there has been an increase of farmers’ average age and land concentration in bigger properties.

Rafaella petting her favorite cow, Fortuna.

My grandpa just loved his land to the point that he cared more about the cows eating the best type of feed he could get than making a profit out of the milk he sold to the local cooperative. And that was simply not enough for the us to keep the farm.

After graduating from Harvard Business School (HBS) in May 2023, I spent some time with my parents—now living in a different region of São Paulo state’s countryside. It was my conversations with them that fueled this article. On a Sunday morning, while my dad and I were watching “Globo Rural” (the same farming TV show we used to watch with my grandpa), he exclaimed judiação – an expression in Portuguese for empathy and sadness. He was referring to the news on small farmers losing their crops, their livestock and their houses to torrential rain and floods in the South.

This prompted two thoughts for me. First, the farmers on the screen (all elders) did remind me of my grandpa and of the reasons why my family sold the farm 18 years ago—no wonder the youth is leaving the countryside, where the risks can be so high. Second, that extreme weather event made me think about how climate change is happening today. As much as my grandpa adored nature and cared for it, he probably never heard anything about it—let alone about climate friendly food products such as a low carbon milk.

These emerging consumer trends have been fueling sustainable and organic farming movements, which many times are associated with small farms. According to Embrapa, 15% of Brazil`s urban population buys organic produce but only 0.3% of the country`s rural properties are organic certified (about 15,000 out of five million properties). More than half of these organic farms are located in the south/southeast of Brazil, where many properties are small and where several technical extension institutions support that type of farming management.

I believe organic farming could allow some families to stay in their farms by increasing their operation’s profits, especially due to organic premium prices and direct to consumer sales—but this does not change how hard it is to manage a farm operation. If anything, the organic practices and certification make it more complex and demanding.

These facts and my own family’s journey make me wonder about ways to bridge the gap between farm to fork and reestablish the connection to the land—a return after so many departures. More often than not, I think we create this bucolic view of small farms (and discount the hardships of being a rural producer) while villainizing big properties—whereas all play their role in the country’s agribusiness economic activity: about 25% of Brazil’s GDP depends on the whole agribusiness value chain, ¾ of that value is created on large commercial operations and the remaining share comes from family ones.

Brazil is a global leader in coffee beans, corn, beef, poultry, pulp, soybeans, and sugar exports. Most of these crops are produced in large, commercial properties—16% of the country’s rural properties occupy most of the land and produce 90% of the output while family farms represent around 80% of the number of properties but occupy 23% of the farmland area.

Rafaella petting a Nelore calf, with farm dogs Urso and Banditi.

I never returned to the land where I spent most of my childhood. I did become an Agronomic Engineer, inspired by all the lessons and values my family taught me, and built a career in agribusiness. In 2021, I moved to Boston to start my Master in Business Administration (MBA) program in the hopes of becoming a leader who can change the farming world for the better.

With all the global challenges humanity faces, I feel still pretty far from “becoming that leader”; and even further away from the farm of my childhood, living in the United States and working for a startup headquartered in Australia.

Rafaella’s family farm region, as of 2023

I don’t recall ever feeling so heartbroken as in that spring afternoon in 2005, leaving for good the place most associated to my childhood identity. With challenges such as climate change, some days I feel hopeless. But, as one of the “Globo Rural” farmers who lost everything in the flood said in an interview, “we will start over again.” Today, dedicating my career to agribusiness and sustainability feels like a vocational calling to honor my childhood memories. For now, this is my return to my roots.

Rafaella Mazza was named after her grandfather, Rafael Mazza. She is an agronomist from Brazil and was a first-generation student—she received a Harvard Business School MBA in 2023 and is currently working to tackle livestock methane emissions.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Agriculture and the Rural Environment

From agribusiness to climate change to new alternative crops, agriculture faces an evolving panorama in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Local “sweetening” of the Cocoa Commodity? Alternative Economies in the Peruvian Amazon

The road was nearly impassable again because of the rain.

Agro-technological Revolutions in Latin America

When we speak about a revolution in agriculture in Latin American history, most scholars rightly think of peasant revolts, land tenure struggles or commodification of crops, to name a few of the most salient themes.