How Museums Shape (Post)Colonial Identities in Ecuador and Beyond

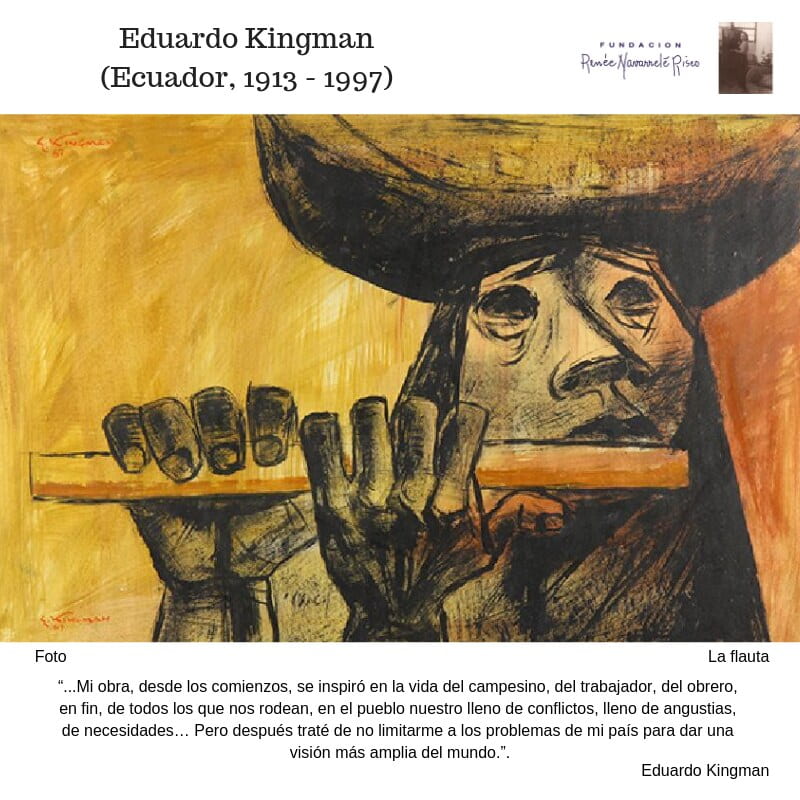

As a study abroad student in Quito, Ecuador, about ten years ago, I wandered through the living spaces of Eduardo Kingman (1913-1997), an influential modernist painter. The rustic old house, which had once been a bakery, sat perched upon a hilltop in Quito among lush trees and bushes. Kingman’s paintings adorned the walls, depicting various landscapes and stylized figures. Especially striking to me were his iconic paintings of indigenous laborers, whose muscular arms, narrow wrists, broad palms and curved, modular fingers— focal points of his compositions—foregrounded the excruciating and exploitative nature of manual labor to which they had been subjected both during and after colonial rule.

Kingman was a contested yet eventually celebrated Ecuadorian artist in the mid-20th century, often called the “painter of hands” and a leading figure in Ecuador’s “Pictorial Indigenist” movement. His masterpieces still hang in major museums both in Ecuador and abroad. The particular museum I visited, however, was striking in that it presented the intimate spaces that Kingman had occupied for thirty years of his life, including his bedroom, studio, dining rooms and kitchen, and alongside his modernist paintings, it displayed Kingman’s personal collection of colonial art, including nude sculptures from the 17th century and gilded religious icons; paintings by other Ecuadorian and international artists; his antique furniture; musical instruments; personal photographs; a collection of pens, brushes, an easel and other art supplies; and various sketches, watercolor paintings and oil paintings that he had left unfinished. The museum offered a glimpse into the private life of and diverse influences on a public figure whose work is now often considered canonical to Ecuadorian national culture.

Eduardo Kingman, Galeria Kingman Vanessa Espinel/DiseñoFotografico/LaMetro Flikr

Museums, like the Eduardo Kingman House Museum, are important sites where visitors learn about cultural objects, and through those objects, about people and nations. By displaying some objects but not others, allocating them to spaces with varying levels of visibility and prominence, situating them in clusters, labeling them with titles and captions, managing how light and shadows move around them and using various other strategies, museum curators and managers construct narratives that give meaning to these artefacts and the communities they represent. Such exhibitions have been particularly important tools used to consolidate national identities, values and aspirations. According to sociologist Peggy Levitt, throughout history, “museums not only created nations but also justified their imperialist projects” (Artefacts and Allegiances, 2015, p. 7). They have done so by representing both national “insiders,” with whom citizens are expected to identify, and “outsiders,” who may be cast as allies, enemies or exotic “others.”

At the time when Kingman was working, questions pertaining to national heritage and belonging, especially in the aftermath of colonialism, were salient in Ecuador and throughout many other parts of the world. In the 1930s, the rise in fascism caused a shift in international alliances in the Americas and beyond. Kingman was among those Latin American artists who sought to differentiate their work from European models that had long dominated the local art world. He was heavily influenced by the Group de Guayaquil, a Marxist collective of artists and writers based in the coastal Ecuadorian city, and looked to developments in the Americas, such as the Mexican muralist movement, for inspiration.

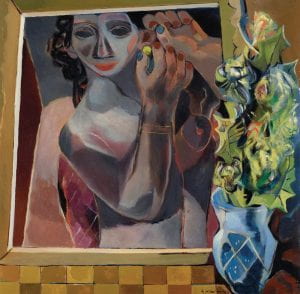

Eduardo Kingman – El espejo (1946) Flikr

Yet, as art historian Michele Greet explains in Beyond National Identity (2009), Kingman engaged with the themes of indigeneity and post-colonial national identity somewhat differently than the influential Mexican muralist Diego Rivera and other Ecuadorian artists such as Camilo Egas working in this tradition. Whereas Rivera and Egas tended to depict pre-industrial, pre-Columbian scenes in a utopian light, using indigenous motifs to foreground an ethnic heritage and inspire national pride, Kingman foregrounded these people’s current exploitation. Greet writes, “By revealing contemporary social circumstances, Kingman therefore challenges the elite’s claim to the pre-Conquest past—in its efforts to construct a unified national identity—without first taking responsibility for the present” (113).

What struck me most about the Eduardo Kingman House Museum is that instead of partitioning artists and their work into discrete eras and art movements, as many museums do, it highlighted the continuities between them. It depicted Kingman as a man with a liberatory, postcolonial vision for the Ecuadorian nation, yet living among and shaped by the remnants of a long colonial history. Rather than celebrating Ecuadorian nationhood, the museum celebrates the life a man who grieved, loved, critiqued, embodied and sought to transform the multifaceted society he called home.

Eduardo Kingman – La Flauta Jose Botto/Flikr

Museums deal with colonial histories in diverse ways, sometimes resisting and deconstructing colonial models and at other times upholding them. They construct visions of national unity on diverse grounds—such as ethnic ancestry, residence in a geographic territory or shared civic values. Museums are, in other words, ideological spaces. They tell stories to shape identities in politically motivated ways. As such, they can be tools of resistance or subjugation. To understand what they do, and how, it is important to understand the motives of the people who control them. The same strategies can be used towards different ends in different contexts. And the meanings that people derive from the objects displayed in museums are not so easy to control. Paintings, sculptures and other cultural objects can be read in diverse ways and sometimes take on a life of their own.

Consider an example from my own research, which is based in the former Soviet Union—specifically Lithuania, a Baltic state that now forms part of the eastern border of the European Union. When I studied abroad in Ecuador and first encountered Kingman’s art years ago, I didn’t notice the similarities between Kingman’s figures and the many mosaics, murals and sculptures designed in the social realist style which, to this day, adorn some public spaces throughout Lithuania. You see, my grandparents fled Lithuania during the Second World War, so the language, stories, images and traditions that they carried from their homeland and fostered in my family life harked back to a pre-Soviet time. But during the approximately five decades when Lithuania was under Soviet rule, different narratives and aesthetic norms came to dominate public life in Vilnius. When I arrived in Lithuania in 2018 to study representations of historical narratives in urban public spaces, I became fascinated by these remnants of the Soviet era.

To offer me a glimpse into this unfamiliar time, my uncle Antanas (pseudonym assigned to protect his anonymity) took me to Gruto Parkas – an open-air museum established to display Soviet monuments, propaganda posters, paintings and other cultural objects that had been removed from public spaces when a Lithuanian sovereignty movement gained traction and independence was finally restored (1991). I should mention that Antanas is not really my uncle. He is technically my grandmother’s cousin’s son, her last remaining relative in the country her family fled when she was about seven years old. Around the same time, Antanas’ parents were deported to Siberia, where he was born and lived until Stalin’s death. Together, we meandered between monuments to Lenin, Stalin, Marx, Lithuanian communist leaders and dozens of anonymous Soviet soldiers, workers and youth as he shared memories from another time. We listened to Russian music broadcast through loudspeakers, perused propaganda posters and banners in an indoor exhibit, observed one of the many multi-colored metal playgrounds that had been installed throughout the Soviet Union and reminisced about my family’s first visit to Lithuania in 2001, when I had played in one of the “European-style” playgrounds built to replace these Soviet structures.

Art commissioned and constructed within the Soviet regime was highly regulated and often propagandic in nature, as officials sought to ensure that it upheld narratives consistent with a communist ideology. Interestingly, the sculptures and paintings in Gruto Parkas shared many themes and design qualities with Kingman’s paintings and the art of other modernist Ecuadorian painters working in the mid-20th century. For example, I saw some paintings, mosaics, prints and sculptures illustrating laborers hard at work, rendered using somewhat abstract, stylized forms and exaggerated features. But unlike in Ecuador, where these types of art objects challenged a hegemonic system rooted in a history of Spanish colonialism, here, they had been displayed to bolster a system imposed through violent, imperialistic means. Gruto Parkas depicted social realist art forms as remnants of a painful colonial past—that which was decidedly not Lithuanian.

In these two contexts, displays of social realist art in museums and other public spaces were used towards different political ends. They were deployed in one place to liberate and the other to justify an imperial project. Similarities in the artists’ choices of content and form were not entirely happenstance. In fact, throughout history, there have been many transnational exchanges between Latin American artists and those in Eastern Europe, allowing them to share ideas and inspiration. Museums have played an important role in facilitating these international connections.

For example, exhibitions of Latin American art were common in the former Soviet Union. They were organized to foster identification with an international working class, and to thus construct “global Soviet citizens” throughout the USSR’s constituent republics. According to art historian Laura Petrauskaitė (https://academies.hypotheses.org/9295), these exhibits, as well as exchanges with diasporic artists in Latin America, had a fundamental impact on modernist artists in Lithuania, but not always in ways anticipated by governing officials. Consider, for instance, this reflection offered by Lithuanian sculptor Vladas Vildžiūnas in a 1997 film by directors Juozas Matonis and Vytautas Damaševičius (my translation from Lithuanian, edited for clarity):

When I was already in my fourth year of study, a big exhibition of old Mexican art was brought to Moscow. Art historians in Moscow say that there hasn’t been such an exhibition in two hundred years. Well, it was actually very good, an inspiring exhibition. And what was interesting to me was that there were these huge stone sculptures and an endless amount of small ceramics. What really left an impression on me was how several small sculptures, just a few centimeters tall, were magnified by a hundred times, and so these things looked like monuments. And that helped me to look at the Lithuanian folk sculpture. Then I started making slides and displaying them on the wall, also enlarging them up to a dozen times. And only then I saw what was in that sculpture of our people. And the power of transformation, the power of monumentality, and so on.

A second major influence upon Vildžiūnas’ development as a sculptor, he says, was encountering Henry Moore’s sculptures. He said, “It was also very interesting to me that his point of departure and influence for many years was also the sculptures of old Mexico. His relationship with Mexico, and the relationship between Lithuanian folk sculpture and the old Mexican art, for me, set important points in my own path to understanding and forming an aesthetic program.” For Vildžiūnas, exhibitions of Latin American art and exposure to sculptures influenced by Latin American traditions inspired him to look more closely to an indigenous Lithuanian folk culture, rooting, as opposed to de-territorializing, his conception of citizenship and national belonging.

Vildžiūnas’ reflections, my experiences abroad and work by other scholars suggest that by housing, displaying and interpreting cultural objects, museums influence how we come to see ourselves in relation to others. They tell us who we are and who we are not, shaping both national and transnational identities. They can give space to voices challenging colonial and other hegemonic structures or, on the hand, consolidate the power of empires and elites. Managers of museums have considerable power to shape people’s worldviews. However, their influence reaches a fine limit, as objects can tell their own stories, inspiring onlookers in unexpected ways.

Andreja Siliunas was born in the Chicagoland area, where she grew up immersed in a diasporic Lithuanian community. She attended college in rural Ohio, studied abroad in Ecuador and is currently completing her Ph.D. in Sociology and Social Policy at Harvard University. Her dissertation examines how contested national narratives are represented in public spaces throughout Vilnius, Lithuania, in the form of public art.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.