Returning Our History

Repatriation of Peruvian Cultural Patrimony

It was August 2017 and I had just become the General Director in Defense of Cultural Patrimony in the Peruvian Ministry of Culture. An e-mail from a special Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) agent specialized in crimes against cultural patrimony suddenly came across my desk. The message was very clear. One of the colonial-era canvases, which Peru had reported as stolen, had been located not internationally, but in Peru itself.

The message advised me that the FBI would not get involved, that it was the Peruvian state as the owner of the nation’s cultural rights that would have to take action.

A Little History

Since the arrival of the Spanish in 1532, Peru has been one of the territories most affected by looting and plunder of the various cultures in these lands, the imposition of Spanish religion and customs for more than three centuries, resulting in new ways of life and an ample cultural mixing of races, giving birth to the country we have today.

Our pre-Hispanic cultures go back to at least 3,000 years BC with a diversity of knowledge that permitted the creation of innumerable objects—decorative, utilitarian and religious and that today, perhaps, can be found at some sale or auction or as part of important collections overseas.

Since the Conquest to our independence in 1821, indigenous peoples with their productive hands also understood and adapted their abilities to the art and culture of the foreigners, while leaving their own stamp. The process of evangelization during colonial times sought to eliminate the Andean cosmovision, their beliefs, customs and values handed down by the ancestors. The communities and peoples also kept objects inherited from their forebears such as little statues, figures, amulets, idols, in and of themselves, objects that they worshipped and that were important to them as indigenous peoples.

In the midst of clashes between Royalists (Spaniards) and patriots, José de San Martín, the Argentine considered to be the liberator of Peru, issued decree N° 89 on April 2, 1822, banning the export of archaeological patrimony. More recently, in 1931, a similar restriction was placed on historical patrimony. Despite these edicts, our patrimony is still coveted, maintaining illegal contraband routes that continue to diminish our heritage.

During the Conquest, evangelization was crucial: Catholic churches were constructed over important pre-Hispanic buildings (huacas), incorporating murals, altars elaborated in gold and silver, wood carvings, canvases painted by indigenous hands, creating this symbiosis, syncretism and mixing of the races in cultural expressions.

The Reaction

After we received the news that the painting had been found, we immediately organized a trip to the southern part of the country, and, together with experts, we decided that the first priority was to confirm that the painting was indeed the original we were looking for. To achieve this, one of the art historians traveled undercover to the place the canvas had been found to authenticate it. It was in a well-known and exclusive hotel in one of Peru’s most touristic cities.

The canvas, “Cain building the city of Enoch,” was indeed an original work of art in good condition. After the visit, we decided to talk to the representative of the hotel union in the region to express the necessity to remove the painting from the hotel lobby and to place it in the custody of the Peruvian state.

We thought about almost all the possibilities, including the use of police force; however, that was not necessary. When we commented on the history of the canvas to the hotel administrators, we were met with an open attitude, and they put themselves at the disposition of the experts, as well as the authorities. I must admit I was pleasantly surprised.

Origin of the Canvas and the Series

The canvas found in 2017 belonged to a series of twenty paintings called “The Creation Until the Flood,” which depicted Biblical scenes about the creation of the world from the Old Testament, and is a reinterpretation made by a disciple of the Cuzco master painter Diego Quispe Tito (1611-1681), eminent representative of the 17th-century Cuzco School, with inspiration from the engravings of Flemish artist Johan Wierix (1549-1620).

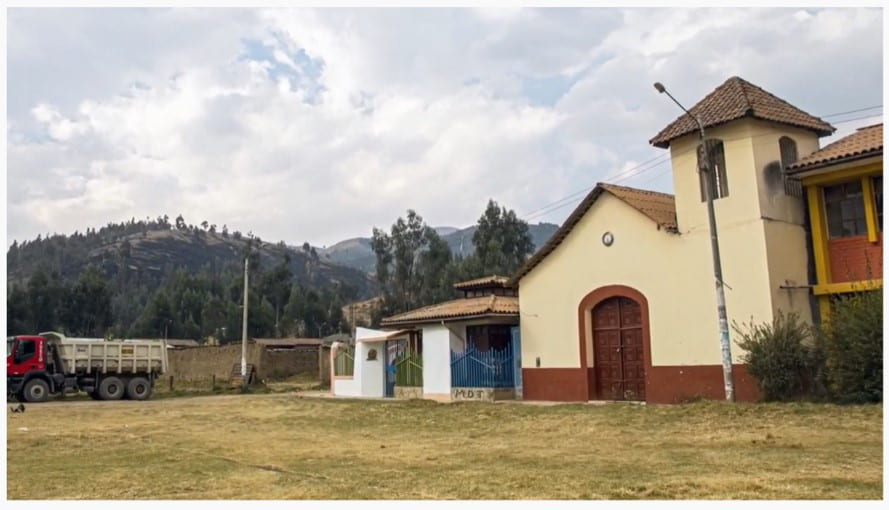

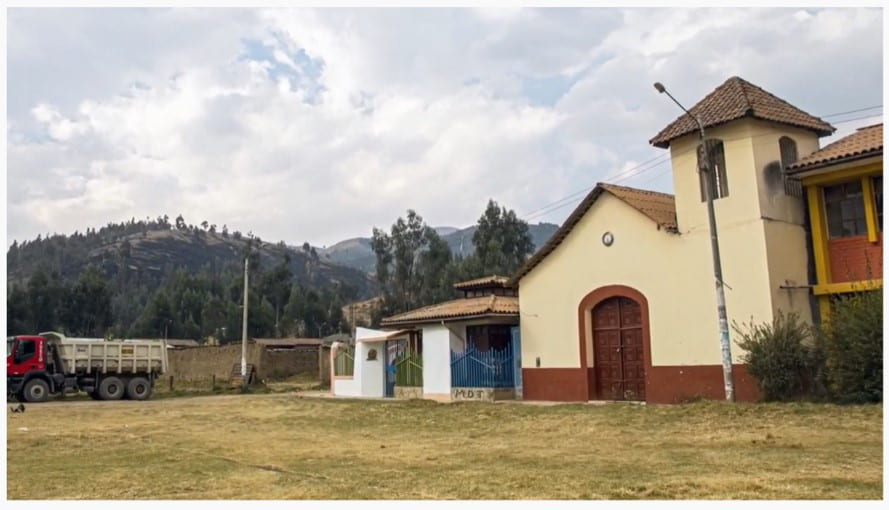

The series was hung on the walls of the Chapel of the Virgen del Rosario in Hualahoyo, a town on the outskirts of Huancayo in Junín, in the center of Peru. All the artwork has been systematically robbed or disappeared since the 1980’s.

Part of this series has been recovered. For example, three canvases were seized by the Chilean authorities in the year 2000; two were returned voluntarily by a U.S. citizen and another was recuperated while it was being sold at a famous auction.

How did that last painting get to the hotel? It happens that, most of the time, attention is focused outside the country because the illegal traffic of cultural goods has developed international circuits with their own dynamic, crossing border and after a certain amount of time, with luck, we see this patrimony in a private collection or at some auction. This particular canvas was in Peru and that made it particularly important and shocking.

Peruvian Efforts

As we’ve seen, the objects and goods produced in this territory have in one way or another been removed, leaving only collective memories, yearning for customs and a long-ago past, both the tangible and the intangible.

Despite the complicated, long and expensive legal processes to repatriate cultural patrimony, the Peruvian state has been making notable efforts to recuperate and bring back its cultural legacy. It is one of the countries that has recovered the most patrimony in recent years.

When a piece that belongs to Peru’s patrimony is found in some part of the world in an illicit fashion, one of the most complex difficulties is to demonstrate that the piece in question is Peruvian. In many cases, the articles have not been previously registered or inventoried, a process that would verify their provenance—particularly in the case of preHispanic and archaeological pieces—precisely because they were huaqueados, looted from sacred places or ceremonial sites although export of these pieces without permission has been prohibited for more than 200 years.

Does that mean that the legal export of Peruvian cultural patrimony is possible? Yes, indeed. Law No. 28296, the General Law of Cultural Patrimony of Peru, declares there are only three cases in which cultural patrimony can leave the country temporarily: a) for exhibitions b) for specialized studies or restoration that cannot be performed within the country and c) as property of a diplomatic mission. The law prohibits without exceptions the permanent export of cultural patrimony.

Peru has subscribed to bilateral and multilateral agreements and conventions as cooperation mechanisms to achieve the return of its cultural patrimony, for example, the 1970 UNESCO Convention. Vincent Negri, the researcher for the Institute of Social Sciences of Political Affairs at the Superior Normal School of France, observes, “The Convention opened the way for the rights of indigenous peoples to maintain their own cultures and, because of this, it is a legal instrument of great importance to counter the looting and illicit traffic of cultural patrimony.”

In the year 2020, at Peru’s initiative, the Andean Community of Nations (CAN) approved Decision 861, a norm that would substantially improve the safeguards for the integrity and curbing illicit traffic of cultural patrimony from Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru, mainly in what is referred to as the “burden of proof,” which obligates the person who possesses the cultural good to accredit the legality of its title.

One of the most important and effective bilateral treaties is the Memorandum of Understanding with the United States, signed in 1997 and renewed every five years. This memorandum prohibits the entry into U.S. territory Peruvian cultural patrimony that does not have the necessary authorization from the Peruvian state, that is, a ministerial resolution signed by the head of the culture ministry. In the last renewal in 2017, documents as cultural goods were also included. This year, the Peruvian state, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Culture Ministries are taking the necessary steps to renew the Memorandum.

In this constant work, Peru, through the web platform Consulta de Robos de Bienes Culturales, publishes the pre-Hispanic, colonial, republican and contemporary objects that unfortunately have been robbed, lost or otherwise unaccounted for. It is a webpage in which the greatest amount of information is entered to convoke all interested parties to collaborate and help in this feat of finding the lost objects and attempting their return.

“Visa” for the Return

There are several ways to return an object of cultural patrimony. The diplomatic option has been and continues to be fundamental for successful restitutions; with its own times and processes, it has come to give very good results in the return or surrendering of cultural patrimony.

The voluntary return is another path used by individuals or organizations, private collections in favor of the communities that have in some way have awaited the return of an important piece, part of their heritage. This demonstration of good will is a shift in paradigms.

Those who take this path do it from their generosity and with a great sense of ethics; they have understood that the correct thing is to return these objects to their true heirs; these actions are transformed into examples to be followed worldwide.

The Exhibition

After recovering the painting, in 2019, in coordination with the Peruvian Foreign Ministry, an exhibit entitled “From the Creation to the Flood: The Hualahoyo Canvases” took place in the Torre Tagle Palace in Lima’s historic center, open to the public until September 2022. The exhibit is still available online, urging those who know anything about the other missing paintings in the series to collaborate in their recovery.

Virgen del Rosario Chapel in Hualahoyo

Constant Work and Work to be Done

Although we still have much cultural patrimony to recover, articles taken out of the country without authorization that are still in legal processes between different countries, articles that have been at auctions or lawsuits for actual losses. The Peruvian state is clearly making valiant efforts to combat illegal trafficking, including the fact that points of revision or verification now exist in some airports and border regions, but it is not enough.

A negative aspect of that positive measure is that some visitors have a very rough time when after having had a lovely touristic experience, they have to cope with police authorities at the airport who revise their luggage thoroughly because some huaco or “Chancay doll,” a souvenir of their visit, has shown up on the scanner. Many of them had not been informed that such items cannot leave the country.

Canvas “Caín construye la ciudad de Enoc”

Another challenge is that up until now there are few museum-like spaces in conditions to receive the articles returned to the communities or indigenous peoples from which they had been plundered. Nevertheless, in 2021, Peru opened the doors of the National Museum of Peru (MUNA), a building set up to make known and demonstrate with pride our great heritage.

Another pending aspect is the continual work with the state so that the voluntary return of cultural patrimony becomes more frequent and that these pieces be returned and exhibited, either in a museum space to which we can all have access and learn more about or culture or by taking advantage of technology, as in the case of the exhibit Exposición Virtual “Patrimonio Recuperado, Bienes de nuestra Identidad Cultural,” promoted by the Recovery Unit of the Ministry of Culture in Peru, to which we all have been invited.

El retorno de nuestra historia

La repatriación de los bienes culturales peruanos

Era agosto del 2017 y acababa de asumir el puesto como Directora General de Defensa del Patrimonio Cultural en el Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. De repente, un correo electrónico enviado por una agente especial del Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), especializada en crímenes contra los bienes culturales, llega a mi buzón de entrada. El mensaje era clarísimo. Uno de los lienzos de nuestra época colonial, que el Perú había reportado como robado, había sido ubicado no fuera, sino dentro del país.

Me avisaban que no podían intervenir, era el Estado Peruano como titular de los derechos culturales de la Nación, quien debía tomar acciones.

Un poco de historia

Desde la llegada de los españoles en 1532, el Perú ha sido uno de los territorios más afectados por los saqueos y expolios contra las distintas culturas que se desarrollaron en estas tierras. La imposición de la religión y los modos de vida españolas que se asentaron por más de tres centurias, trajeron como consecuencia nuevas costumbres y un amplio mestizaje cultural, dando como resultado el país que hoy tenemos.

Nuestras culturas prehispánicas se remontan a por lo menos 3000 años antes de cristo; con una diversidad de saberes que permitieron crear un sinfín de objetos decorativos, utilitarios, de culto o adoración y que hoy, de , son encontrados en alguna venta o subasta o como parte de importantes colecciones en otras latitudes.

Desde la conquista hasta nuestra independencia en 1821, los indígenas con sus manos productivas también aprehendieron y adaptaron sus capacidades a las artes y la cultura de los foráneos, sin dejar de tener una impronta especial. El proceso de evangelización durante la colonia tuvo como uno de sus objetivos la eliminación de la cosmovisión andina, sus creencias, costumbres y valores que se habían mantenido ancestralmente. Las comunidades y pueblos mantenían también objetos heredados de sus antepasados como estatuillas, figurinas, amuletos, ídolos, en sí, objetos a los que aún se les rendía culto y seguían siendo importantes para los naturales.

En medio aún de los enfrentamientos entre realistas (españoles) y patriotas, el libertador del Perú, el argentino don José de San Martín emitió el Decreto Supremo N° 89 del 2 de abril de 1822, prohibiendo la exportación de bienes culturales arqueológicos. Recién en 1931 se daba la misma restricción para los bienes históricos. Pese a ello, nuestros bienes culturales siguen siendo codiciados, manteniéndose rutas ilegales que siguen menguando nuestra herencia.

En efecto, durante la conquista, la evangelización fue crucial: las iglesias católicas fueron construidas sobre los edificios prehispánicos importantes (huacas), incorporando murales, altares trabajados en oro y plata, tallas de madera, lienzos hechos por manos indígenas, generando esa simbiosis, sincretismo y mestizaje también en las expresiones culturales.

La reacción

Luego de la noticia de la ubicación del lienzo, de inmediato organizamos un viaje al sur del país y, junto a los expertos, resolvimos que lo primero era confirmar que el cuadro ubicado era en realidad el original que estábamos buscando. Por eso, uno de los historiadores del arte se apersonó de incógnito al lugar para su verificación. Era un conocido y exclusivo hotel de una de las ciudades más turísticas del Perú.

El “Caín construyendo la ciudad de Enoch” era original y se encontraba en buen estado. Tras la visita, se tomó la decisión de conversar con el representante del gremio de los hoteles de la zona, considerando que lo que correspondía era retirar el bien del living donde se encontraba y ponerlo bajo la custodia del Estado.

Pensamos en casi todas las posibilidades, incluso el uso de la fuerza policial; sin embargo, ello no fue necesario. Al comentar sobre la historia del lienzo a los administradores del hotel, recibimos la máxima apertura, poniéndose a disposición tanto de los expertos como de las autoridades. Debo confesar que me sorprendí gratamente.

Origen del lienzo y la serie

El lienzo encontrado en el 2017 pertenece a una serie de veinte lienzos denominada “La Creación hasta el Diluvio” que representa escenas bíblicas del antiguo testamento sobre la creación del mundo, y es una reinterpretación realizada por manos de un discípulo del maestro cusqueño Diego Quispe Tito (1611-1681), eximio representante de la escuela cusqueña del siglo XVII a partir de grabados del artista flamenco Johan Wierix (1549-1620).

La serie estuvo en las paredes de la Capilla Virgen del Rosario de Hualahoyo, un pueblo a las afueras de Huancayo en Junín, en el centro del Perú. Todos robados o sistemáticamente desde los años ochenta.

Parte de esta serie ha sido recuperada. Por ejemplo, tres lienzos fueron incautados por las autoridades chilenas en el año 2000, dos lienzos fueron devueltos de manera voluntaria por una ciudadana estadounidense y uno más se pudo recuperar al paralizar una venta en una subasta famosa.

¿Cómo había llegado el cuadro a un hotel dentro de Perú? Sucede que, la mayoría de las veces, la atención está fuera del país porque el tráfico ilícito de bienes culturales ha desarrollado rutas internacionales con su propia dinámica, atravesando fronteras y luego de mucho tiempo y con suerte, volvemos a ver los bienes en una muestra privada o en alguna subasta. Este lienzo estaba en el Perú y eso lo hacía especialmente importante e impactante.

Los esfuerzos peruanos

Como vemos, los objetos y bienes producidos en este territorio de una u otra forma han ido trasladándose y dejando solo recuerdos en las memorias colectivas, añorando costumbres y un pasado milenario, tanto de lo tangible y de lo .

A pesar de los complicados, largos y costosos procesos judiciales con el fin de repatriar sus bienes, el Estado Peruano ha venido haciendo notables esfuerzos por recuperar y traer de vuelta su legado cultural, siendo uno de los países que más patrimonio ha conseguido recuperar durante los últimos años.

Cuando una pieza perteneciente al patrimonio del Perú se encuentra de manera ilícita en algún lugar del mundo, una de las dificultades más complejas es demostrar que la pieza es peruana y es que no se cuenta con un registro o inventario previo en el cual se verifique esa condición, sobre todo los bienes arqueológicos o prehispánicos, por haber sido “huaqueados” (por la acción de excavar en las huacas o centros ceremoniales) a pesar de que hace más de 200 años se prohibió su salida sin un permiso que así lo autorice.

¿Significa que es posible una salida lícita de los bienes culturales peruanos? Así es, la Ley N° 28296, Ley General de Patrimonio Cultural del Perú, dispone que existen solo tres casos en que se puede autorizar la salida temporal de los bienes culturales: a) por motivos de exhibición, b) por estudios especializados o restauración que no pueda realizarse en el país y c) como propiedad de una misión diplomática; y se prohíbe de manera taxativa la salida del país de bienes culturales de manera definitiva.

El Perú ha suscrito convenios bilaterales, multilaterales y Convenciones, como mecanismos de cooperación para lograr el retorno de sus bienes; por ejemplo, la Convención de 1970 de UNESCO. Señala el investigador del Instituto de Ciencias Sociales del Ámbito Político de la Escuela Normal Superior de Francia, Vincent Negri que “(…) la Convención abrió la vía al derecho de los pueblos a disponer de sus propias culturas y, por eso, es un instrumento jurídico de gran importancia para contrarrestar el saqueo y el tráfico ilícito de los bienes culturales”.

En el año 2020, a iniciativa de Perú, la Comunidad Andina de Naciones (CAN) aprobó la Decisión 861, norma que dispone mejoras sustanciales en relación a la salvaguarda de la integridad y no circulación ilícita de bienes patrimoniales de Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia y Perú, principalmente en lo referido a la “carga de la prueba” que obliga al poseedor del bien cultural a acreditar la legalidad de su titularidad.

Uno de los tratados bilaterales más importantes y eficaces es el Memorando de Entendimiento con los Estados Unidos, suscrito en 1997 y que se renueva cada cinco años. Este MoU prohíbe el ingreso al territorio estadounidense de bienes culturales peruanos que no cuenten con la debida autorización emitida por el Estado Peruano, es decir, una Resolución Ministerial firmada por el titular del sector . En su última renovación, en el año 2017 se incluyeron los bienes de carácter documental. Durante este año 2022, el Estado Peruano, a través de la Cancillería y el Ministerio de Cultura, realiza las gestiones necesarias para su renovación.

En este constante trabajo, el Perú, a través del portal web Consulta de Robos de Bienes Culturales publica los objetos prehispánicos, coloniales, republicanos y contemporáneos que, lamentablemente han sido robados, perdidos o se encuentran como no habidos. Se trata de una página en la que se intenta colocar la mayor información con la que se cuenta a fin de convocar a todos los interesados en colaborar y ayudar en esta hazaña de encontrar lo perdido e intentar su devolución.

“Visa” para el retorno

El retorno tiene varias vías. La vía diplomática ha sido y sigue siendo fundamental para restituciones exitosas; con sus propios tiempos y procesos, han llegado a dar muy buenos resultados en la devolución o entregas de los bienes culturales.

La devolución voluntaria, es otra vía utilizada por personas naturales o entidades, colecciones privadas a favor de las comunidades que de alguna manera han esperado el retorno de una pieza importante, parte de su herencia. Esta manifestación de voluntad es un cambio de paradigma.

Quienes toman este camino, lo hacen desde su liberalidad y con un gran sentido ético, han entendido que lo correcto es retornar estos objetos a sus reales herederos; y estas acciones se convierten en ejemplos a seguir a nivel mundial.

La muestra

Luego de la recuperación del lienzo, en coordinación con la cancillería peruana en el año 2019 se realizó una exposición en el Palacio Torre Tagle en el Centro Histórico de Lima llamada “De la Creación al Diluvio. Los lienzos de Hualahoyo”, abierta al público hasta septiembre de ese año. Aún es posible tener acceso a los cuadros a través de este enlace manteniendo el llamado para que quienes los conozcan colaboren en su recuperación.

Capilla Virgen del Rosario de Hualahoyo

Trabajo constante y pendiente

Aún tenemos mucho por recuperar, bienes que salieron irregularmente, que aún están bajo un proceso judicial entre Estados, bienes que son subastados o denuncias por pérdidas actuales. Es claro que desde el Estado Peruano se realizan valerosos esfuerzos para combatir el tráfico ilícito, incluso existen puntos de revisión o verificación en algunos aeropuertos y zonas de frontera, pero no es suficiente.

Un aspecto negativo de esa medida positiva es que algunos visitantes se llevan muy malos ratos cuando luego de pasar una grata experiencia turística, deben además pasar por el pésimo momento en el aeropuerto, con autoridades policiales, quienes revisan su equipaje porque apareció en el escáner un “huaco” o “muñeca Chancay”, tipo “souvenir” o “recuerdo” de su visita al país. Muchos de ellos no fueron informados sobre la prohibición de su salida por lo que hay que difundir más esta medida. mas.

Lienzo “Caín construye la ciudad de Enoc”

Hasta ahora son muy pocos los espacios museales acondicionados para que los bienes que retornan al país sean devueltos a las comunidades o pueblos en donde estuvieron antes de ser expoliados. No obstante, en el año 2021, el Perú ha abierto las puertas del gran Museo Nacional del Perú (MUNA), un edificio adecuado para conocer y mostrar con orgullo, el gran legado que tenemos.

Otro aspecto pendiente es seguir trabajando con los Estados para que las devoluciones voluntarias sean cada vez más frecuentes, y que estas piezas retornen y sean expuestas, sea en un espacio museal donde todos podamos tener acceso y conocer más sobre nuestra cultura o aprovechando la tecnología, como en el caso de la Exposición Virtual “Patrimonio Recuperado, Bienes de nuestra Identidad Cultural” que promueve la Dirección de Recuperaciones del Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, a la que todos estamos invitados.

Leslie Carol Urteaga Peña is a lawyer from the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos-UNMSM, former director general of the Defense of Cultural Patrimony and Cultural Industries of the Peruvian Culture Ministry (2020-2021), and former Vice Minister of Cultural Patrimony and Cultural Industries.

lesurteaga@gmail.com @LeslieUrteaga

Leslie Carol Urteaga Peña es abogada por la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos-UNMSM, exdirectora General de Defensa del Patrimonio Cultural y exviceministra de Patrimonio Cultural e Industrias Culturales del Ministerio de Cultura del Perú (2020-2021).

lesurteaga@gmail.com @LeslieUrteaga

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.