Learning Inside and Outside School

Strengthening Early Childhood Education in Maranhão

2019 was already an unusual year for Laboratório de Educação, the non-profit organization I lead along with Beatriz Cardoso and Andrea Guida. In the five years since I joined this inter-generational team, aligned around a common sense of purpose and a determination to transform knowledge into action, we have confronted technical, financial and ethical challenges that threatened the very existence of our young initiative.

It’s not usual for an independent NGO of our size (with fewer than 10 collaborators) to produce research-based content and strategies that inform professional development opportunities available to educators. Yet, in Brazil, as in many other Latin American countries, few schools of education have organized pre-service training curricula that integrate pedagogical theory as a lens through which to guide and improve practice, rather than solely separate concept from method. As a result, little is known about what makes an effective methodology to equip teachers with the necessary knowledge and tools for professional judgment and action in the ever-changing contexts of Brazilian public schools.

Laboratório de Educação was founded to fill this gap through program development, implementation and research. However, we soon realized that mission did not fit clearly within the available funding boxes for social organizations. Effective communication, flexibility and persistence were some of the ingredients that enabled us to diversify our pool of resources and establish the building blocks for a “proof of concept” back in 2013. We needed to demonstrate, starting with the design of small-scale interventions, how to make research-based practices applicable and teachable to diverse groups of educators with different levels of preparation for their roles within the school system.

Two years later, we piloted an in-service training program to help teachers, pedagogical supervisors, principals and technical staff in municipal departments of education support early language acquisition. Each of these individuals got to play a different role in creating a school environment where children develop language skills at an early age. For instance, principals made sure quality children’s books were available for teachers to use in their classes, while pedagogical supervisors began to lead collaborative planning sessions to ensure those same books were read aloud to spark richer conversations. Midway through the initial implementation cycles, we embarked on a design and piloting process aimed at creating materials and strategies for these same teachers and school personnel to engage parents and guardians of young children in recognizing themselves as educators and strengthening the much-needed school-family relationship.

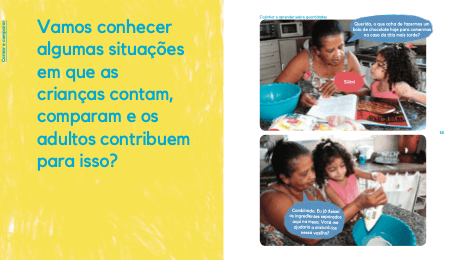

Sample materials developed as part of mobilization strategy to engage parents and caregivers in supporting early childhood education outside the school context: “In what everyday situations do children get to count and compare quantities? How can adults help?”

After working with 1,714 educators, responsible for 26,097 children enrolled in public nurseries and pre-schools in three heavily urban municipalities bordering São Paulo city, we got an opportunity to adapt this methodology to the predominantly rural northeastern state of Maranhão, in partnership with Eneva, an energy company interested in giving back to the communities in which it operates.

2019 gifted us with the time, funding and technical autonomy to immerse ourselves in the challenges facing early childhood education in five municipalities: Santo Antônio dos Lopes, Lima Campos, Pedreiras, Capinzal do Norte and Trizidela do Vale. Our team interviewed a variety of stakeholders, from teachers all the way up to district administrators, ran focus groups with future participants, and conducted school visits and classroom observations. When Andrea, Beatriz and I sat down for dinner after our last on-site meeting in November, we knew the next two years would not be easy: the socioeconomic inequalities between rural and urban schools were rampant, and seemed to have been normalized in response to structural barriers that made even small gains seemingly impossible to achieve.

The rural landscape between Pedreiras and Trizidela do Vale (MA), captured during the research and planning stages of Laboratório de Educação’s early childhood intervention.

In light of these circumstances, we understood that our research efforts had to adopt a formative perspective. We began a collaborative process aimed at compiling data that would help us develop a more accurate picture of the educational reality of these locations. We turned a negative into a positive. The lack of information surrounding multi-year classes in rural schools made a potential opportunity visible to the parties involved. We could design our program in a way that would target schools whose needs had always taken a back seat. We would, of course, not be able to circumvent all of these problems, but after the first month of training in 2020 we felt confident in the path we had chosen to make our support “present” even in spite of the limited amount of professional development time afforded to teachers and school leaders.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit Brazil, two of the five municipalities had suffered from heavy flooding and an outbreak of H1N1, commonly known as swine flu. Schools had been converted into temporary shelters for displaced families, with no end in sight. City governments decided to break early for midyear vacation and, just like that, our partners were in the middle of a humanitarian crisis.

Painfully aware of the limited resources at the municipalities’ disposal, we sought to communicate openly with local administrators to make ourselves available without creating additional burdens to institutions already stretched beyond their means.

Before the public health crisis, we had designed a professional development process that intended to carefully and gradually unpack some of the myths that tend to drive schools and families apart. In these vulnerable communities, we had witnessed how prejudice affects not only the way teachers and principals relate to families, but also influences their beliefs and expectations about children’s potential. We were aware that these attitudes would not change overnight so we invited families into schools to hear what they had to say about their children. Our theory of change was that by modeling and “scaffolding” these kinds of experiences, teachers and principals would begin to establish closer ties with students’ families, while incorporating new strategies into their professional toolbox.

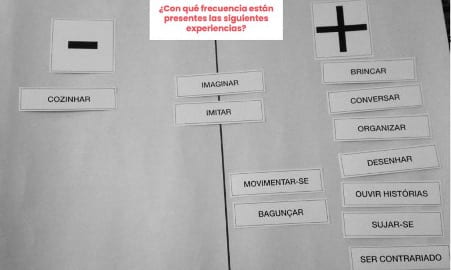

Reflection exercise conducted with school principals and families with the goal of identifying experiences that contribute to children’s learning, as well as how frequently they are part of their everyday routine at home. During our professional development sessions, we encourage principals to develop strategies to communicate to families why and how they may incorporate simple activities such as cooking together to support informal learning.

Whereas in regular times we would put action into educators’ own hands, under these new circumstances, our in-person mediation was out of the question. In addition, with most teachers officially on vacation, it would take a while for districts to come up strategies of their own.

Our efforts to move quickly were motivated by our desire to ensure that no children would be left behind, as well as by a sense of institutional responsibility towards our team and funders. Prior experience with arbitrarily suspended contractual payments reinforced the importance of being proactive and developing plausible scenarios to address the concerns of our partners in both the public and private sectors. We had to navigate uncertainty with rigorous planning that considered everything from a scenario in which we had the means to keep helping the five municipalities, to one in which our sponsors diverted their financial support to immediate local public health needs. All options were on the table.

In this context, we had to be creative and flexible in imagining different courses of action, allowing ourselves to temporarily let go of our “business-as-usual” premise that we would not “do things for” but “with” educators. In other words, we would have to speak directly to families, despite knowing from our earlier pilots that even basic forms of mediation around our content was key to its impact on day-to-day practices.

Given the years that we had invested in our research and development model, we had a structured methodology to lean on, including a book and an app with concrete suggestions for parents and caregivers to encourage child learning by interacting with them during daily routines and household tasks. This approach provided alternatives to continue to educate young children without leaving one’s home or requiring special resources. We could leverage existing tools to respond as quickly as the situation warranted, as long as we identified the right channels.

Months of relationship-building enabled us to approach the Maranhão State Secretariat of Education with a genuine desire to identify points of convergence. We discovered that our five municipalities were not the only ones that had been caught off guard by the present challenge, and that lacked the operational, technical and financial resources to confront them right away.

Social media launch of the state-level collaboration: inviting families of young children throughout Maranhão to access the project’s content.

As the pandemic raged, we chose to strengthen local responses by developing a regional strategy. As a result, in under three weeks, we adapted our family engagement strategies to the Secretariat’s technical requirements for multimedia content delivery through social media, public radio and television channels. The State Secretariat and the Maranhão branch of the National Union of Municipal Education Officers (UNDIME) decided to make Laboratório de Educaçãothe main source of early childhood education content and rapidly managed to convene all 217 municipal administrators to devise targeted plans for outreach to families with limited access to technology.

More than 150 districts regularly distributed our content through schools’ WhatsApp groups, as well as three radio stations and one television network. Over the course of three months, our videos containing book read-alouds and suggestions for parent-child interaction reached over 1.1 million people through social media. In a state where 55% of adults have not completed elementary school and 16% do not have basic literacy skills, our remote learning strategy provided the opportunity for children to hear at least two books each week. Although unexpected, we had found an effective way to achieve one of our long term pre-Covid goals: to democratize access to literature and invite parents to share reading experiences with their children, regardless of their own schooling trajectories.

Example of read-aloud video distributed through the Maranhão State Government’s channels and viewed by a student in her house.

Furthermore, the activities we proposed to transform daily tasks such as cooking and cleaning into opportunities for children to learn about their surroundings have sparked their curiosity and interest, while also contributing to parents’ engagement. We received numerous stories of caregivers sharing favorite recipes with their children or exploring the shapes they can make with shadows before going to bed. Unlike the read-aloud videos (in which the books take center stage), these ideas require parents’ undivided attention and initiative. While we understand the videos are only a starting point, we have seen in practice that, cumulatively, these interactions helped parents and guardians feel more confident as educational agents who can promote informal learning even after the pandemic.

Now that teachers, supervisors and principals have returned to their (now remote) activities and taken an active role in mediating communication with families, our next step has been to foster the very sense of responsibility we had sought to instill through in-person activities. By the end of 2020, we had transitioned to focusing on practice, in order to shift educators’ perspectives towards understanding families as partners they have to work to engage and support, rather than antagonize when expectations are not fulfilled. Part of our intervention in the five municipalities still consists of modeling how to solicit and incorporate feedback from parents about how they and their children have felt as they try out our proposals. We alternate between recording what children have to say and giving room for parents to share their own stories, expectations and preferences—asking, for instance, “How did it feel to teach your child about that game you used to play when you were little?” or “Did you learn anything new about her or him while observing the shapes and colors of the sky today?

Thanks to the knowledge we gathered about the local context and the trust we developed with municipal leaders over the past year and a half, we have been able to celebrate our progress while also examining our limitations with honesty and resolve. Although these conversations are not easy, we need them to remind us that the work will not be completed until the most vulnerable children in each district are served adequately by our actions.

By the same token, we proposed that municipal administrators estimate the number students they had yet to reach in the 2021 school term. Just as in 2019, these research and monitoring tools may shed light on a key dimension of our challenge: to ensure that students whose zip codes do not appear on the map do not fall through the cracks. In the five cities where we support operations more directly, 973 new families began to receive printed materials that also encourage active interaction and exploration of children’s surroundings, but that can be disseminated in villages without internet access.

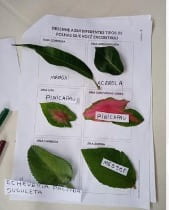

A child from rural village in Lima Campos (MA) organized the leaves she collected on a walk in her neighborhood. One of her parents helped write the names of the trees the leaves came from.

Throughout this process, communicating across such a vast territory using digital tools has proved to be an ongoing learning experience. As we coordinate subsequent actions, we recognize that even seemingly routine operations must adopt a formative perspective that is necessary to achieve our shared objectives.

Finally, as partners in this endeavor, we consider ourselves accountable not just in times of “success.” Looking forward, we hope that through honest and open collaboration we will continue to expand our view of what is possible, so that, regardless of their socioeconomic conditions, every child has access to rich learning environments for the remainder of this crisis and beyond.

Nicole Paulet Piedra holds an Ed. M. in International Education Policy from the Harvard Graduate School of Education and a B.A. in Social Studies from Harvard College. She currently serves as Director of Content at Laboratório de Educação, where she supervises the implementation of professional development programs for public school teachers and administrators.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...