“Travestis in Command of the Nation”

Black Travesti Temporalities and Utopian Horizons in Brazil

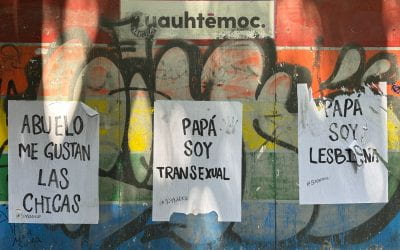

Black travesti activists and artists in Brazil constantly play with notions of time as they build utopian horizons. They look to the past for ongoing forms of historical resistance, they look to the present for stories of resilience among trans elders, and they look to the future with unbridled optimism about potential other worlds. Photos by Carmen Alvaro Jarrin

These temporalities challenge the linear and flat timelines of civilizational thinking and replace them with moebius temporal strips that blur the distinctions between past, present and future. Following the work of Columbia professor Jack Halberstam, we can consider how these travesti temporalities queer the “reproductive temporality” associated with heterosexual inheritance, respectability and nation-building (2005). Travesti temporalities, in contrast to reproductive temporalities, are messier, non-linear and upend notions of respectability. Let’s look at each temporal strategy—past, present, and future—and then use these insights to muse on why utopian horizons matter for political mobilizations based on gender identity.

Let’s start with the past, for the sake of a chronological account that is legible to audiences in the Global North. To be clear, a chronological account is not how travestis would necessarily tell this story. For example, when travestis speak of Xica Manicongo, claimed by the movement as the first travesti in recorded Brazilian history, they invoke her as a return of a violently repressed past.

In an essay titled “Xica Manicongo: Transness Takes the Floor,” the transfeminist scholar and activist Jacqueline Gomes de Jesus reads the historical record against the grain, to recover Francisco/Francisca/Xica from the Inquisition archives that accused her of “sodomy” in 1591, due to her cross-dressing and sexual activities in Salvador de Bahia. As an enslaved, Black person, Xica was obliged to comply in order to survive, and she remained a historical footnote until anthropologists like Luiz Mott and historians of gender and sexuality began writing about her Inquisition case in the 1990s, but mostly wrote about her as a man who had sex with other men.

In the early 2000s, the Black travesti activist Majorie Marchi reclaimed Xica Manicongo as the first travesti in Brazilian recorded history, christened her Xica (since the archives just call her Francisco), and the movement began to celebrate her as a symbol of historical resistance, naming prizes, plays and collectives after her. Gomes de Jesus reflects on the “appropriation and resignification of the historical figure of Xica Manicongo, particularly in the 21st century, as a moment of inflexion for the trans population in relation to their own history” (2019). The memorialization of Xica Manicongo matters because it allowed activists and scholars to reclaim the national past for themselves, occupying history with ongoing Black and trans resistance.

Xica, however, is not simply a historical figure, but a transcestor that still makes herself present among us. In the song “Xica Manicongo,” written by the Black travesti artist Bixarte, Xica is presented as an ancestor worthy of worship:

Xica Manicongo shall be worshipped with gold, frankincense and myrrh,

Xica Manicongo shall be adorned with gold, frankincense and myrhh…

A snowball knows how to move forward without looking back,

Remember that during each fall who saved you was your ancestors,

Vera Verão, Xica Manicongo showed me I am capable,

Clean the dirt off your feet, get out of the bed bicha(sissy)

The reference to gold, frankincense and myrrh compares Xica Manicongo to Jesus and thus describes her as divine as well. She is an ancestor and saint or orixá who lifts up today’s travestis and pushes them to persist despite their difficulties (symbolized by the dirt on their feet). The reference to Vera Verão points towards visible Black queer representation as well, because she was a popular drag character interpreted by the actor Jorge Laffond in several Brazilian comedy shows during the 1980s and 1990s. Today, there are dozens of positive queer and trans Black figures in Brazilian popular culture, but Bixarte reminds her listeners that this was not always the case. She claims it is only white folks who can move forward in history without looking back, creating a more linear temporality (white folks are described in the lyrics as “a snowball”—since most of Brazil never sees snow, it is associated with whiteness and the Global North). Black trans and queer temporalities require the worship and recognition of transcestors to inspire contemporary actions, no matter whether they lived fairly recently (as is the case with Vera Verão) or long ago (as is the case with Xica Manicongo). This rhetoric connects present-day resistance to ongoing historical resistance, threading one into the other.

In the music video for her song “Ancestravas [Travesti ancestors],” the Black travesti singer Ayô Tupinambá makes clear how the present and the past blend into one another. The video is simple, showcasing Ayô as she hangs up photographs or drawings (on a light string) of key figures in travesti history, from Xica Manicongo and Madame Satã (a famous icon of urban queer resistance in early 20th– century Rio de Janeiro), to much more recent figures like the singer Lacraia, who died in 2011, and Dandara dos Santos, who was a victim of a transphobic murder in 2017.

Ayô does not stop there, however, and starts hanging up photos of living trans and travesti activists and artists like Neon Cunha, Bruna Benevides, Erika Hilton, Indianarae Siqueira and herself. The video seems to be implying that these activists and artists, recognized as travesti elders by their own community, are also living travesti ancestors making history in the present. The light string on which Ayô hangs up these photographs shows the continuity between the past and the present, and represents each figure as a luminary lighting the way. The end of the video returns to the drawing of Xica Manicongo and the photograph of Madame Satã, suggesting a circular vision of history rather than a linear one.

The lyrics to the song address not only the past and the present, but connect these to the future in an explicit message about hope and resistance:

Travesti ancestors, matriarchs of many nations,

This ancestral body never needed approval to exist,

Today everyone tries to punish us,

And our only option is to resist so we can exist,

Desisting is not an option, no matter your opinion,

Our vengeance is staying alive,

And believing with hope that we will live our lives in abundance

The lyrics talk about all travestis as possessing an “ancestral body,” that is, a body that has the weight of history behind it, but the song laments that today these bodies are criminalized and punished for simply existing. Nonetheless, these bodies resist by staying alive and by hoping for a future where travestis can lead full, abundant and joyful lives. The past, the present and the future are all inextricably linked in this utopian vision grounded in history and in contemporary activism. As Ayô explains in the text accompanying the music video on YouTube, “Ancestravas [Travesti ancestors] is both a fiction and a promise, it means understanding travestis as ancestral beings. We existed and resisted even before colonization, and we are a technology of the future.” Understanding travestis as eternal beings that are simultaneously ancestral and futuristic creates a utopian horizon that looks both forward and backward in time, engaging in a novel travesti temporality.

The lyrics talk about all travestis as possessing an “ancestral body,” that is, a body that has the weight of history behind it, but the song laments that today these bodies are criminalized and punished for simply existing. Nonetheless, these bodies resist by staying alive and by hoping for a future where travestis can lead full, abundant and joyful lives. The past, the present and the future are all inextricably linked in this utopian vision grounded in history and in contemporary activism. As Ayô explains in the text accompanying the music video on YouTube, “Ancestravas [Travesti ancestors] is both a fiction and a promise, it means understanding travestis as ancestral beings. We existed and resisted even before colonization, and we are a technology of the future.” Understanding travestis as eternal beings that are simultaneously ancestral and futuristic creates a utopian horizon that looks both forward and backward in time, engaging in a novel travesti temporality.

Travestis are unafraid of dreaming of a different future—one in which they are powerful rather than powerless, and one where they command respect rather than being discriminated against. No phrase encapsulates that utopian thinking more than “travesti no comando da nação [travestis in command of the nation],” a phrase that imagines and enacts a different political reality and opens up an otherwise (Povinelli 2002) full of potential and possibility. For example, the Black travesti poet and singer Ventura Profana makes a powerful prophecy in her song “Resplandescente [Resplendent],” claiming that a specific travesti will soon become President of Brazil:

Lascivious blades, our ember is a roaring fire

Around me, I feel life similar to a fortune teller predicting the future

In the Planalto [Palace] I prophesize that a nude Jup do Bairro

Is taking the presidential sash

And is rising, resplendent…

Travestis in command of the nation

Together, we throw a curse

In order to depose the macho and have his God transition

The lyrics describes the embers of travesti activism rising up into a roaring fire and consuming the nation, including the patriarchal machismo and religious intolerance that claims travestis have no place in the halls of power. Instead, Ventura Profana prophesizes from the Planalto Palace (the executive seat of government in Brazil), we will soon see a famous travesti like Jup do Bairro becoming President of Brazil and taking the presidential sash, in the nude. I believe Jup do Bairro was a carefully made choice for this prophecy, because she is a Black travesti artist who proudly identifies as fat and embraces a genderqueer performance of self – she is the farthest you can get from the normative and respectable bodies usually associated with Brazilian politics.

The Black travesti singer and poet Bixarte similarly challenges respectability politics in her song, “Travesti no Comando da Nação/ A Nova Era [Travestis in Command of the Nation/ A New Era],” imagining the patriarchal power of the “macho” as replaced by travesti liberation. The lyrics are quite direct in their indictment of machismo:

The macho who thinks he can silence me with his voice,

The macho who hid the history of Black and Indigenous women,

And who also wants to erase me,

The macho with the presidential sash and the genocidal ambitious against us…

The macho who reaches orgasm with a travesti porno in hand,

The macho who takes pictures of me, sleeps with me, desires me on the floor,

Perhaps your time has come…

The macho who beats his wife will burn in the fire of my Holy Inquisition

The macho who was embarrassed of a travesti will show his sins on the screen,

The macho who from now on will serve me

And call me a lady, Lady Travesti

[At this point, Bixarte laughs heartily in the song]

The lyrics point out the hypocrisy of Brazilian politicians who outwardly condemn and silence travestis, and who embrace genocidal policies against travestis, but who secretly sexually desire travestis. Travesti activists like to point out the contradictions between Brazil being the country that most kills trans and travesti folks in the world, and the country that most consumes trans and travesti porn and sex work. Bixarte predicts the downfall of this ruling order, and the rise of a new Holy Inquisition that shames these men’s sexism against both cisgender (whose gender identity is what they were assigned at birth) and trans/travesti women. There is something very powerful in the reversal of fortunes portrayed by the song, where these macho men “serve” travestis and call them ladies, rather than using them for their pleasure. Bixarte laughs in the face of old moral order and engenders a new one.

This radically “new era” is portrayed as perhaps already in motion, rather than far into the future. It connects the past and the present to the utopian horizons already being imagined and implemented by travesti artists and activists, as dreaming begets new realities. Travesti temporalities refuse the ways in which futurity can sometimes defer dreamsforever, or the ways historicity can be dismissed as irrelevant to our contemporary concerns. Past, present and future are fully imbricated with each other within travesti temporalities, in ways that mess up and queer the clean, linear timelines of civilizational thinking.

Queer and trans theorists like Jack Halberstam rightfully critique the “reproductive temporality” required for patriarchal nation-building, and argue that “queer time” refuses those temporal frames (2005). Cuban American academic José Muñoz adds that this utopian, queer temporality is necessary to produce “a kind of potentiality that is open, indeterminate, like the affective contours of hope itself” (2009: 7). Travesti temporalities relish breaking open time and demonstrating that neither the past nor the future have been written yet, but are still being shaped by the present. Once we shatter the linear timelines, we have assumed to be true, we can see that time is a palimpsest or a collage that folds into itself, like a moebius strip, and that travestis have been in command all along.

Carmen Alvaro Jarrin is Associate Professor of Anthropology at College of the Holy Cross. They are the author of The Biopolitics of Beauty: Cosmetic Citizenship and Affective Capital in Brazil (UC Press, 2017), and co-editor of Precarious Democracy: Ethnographies of Hope, Despair and Resistance in Brazil (Rutgers, 2021). They were a 2021-2022 Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard University.

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.