Making Queerness Ordinary

Santa Muerte and Queer Religious Leadership

I first learned about Santa Muerte one tranquil Sunday evening in Mexico City. Like most Sunday evenings, I was sitting around the kitchen table with my host, taking a break from my work at an education non-profit through the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies’ summer internship program. A friendly Lebanese-Mexican woman in her late sixties, she was sharing carne asada with me when she suddenly mentioned with poignant disdain a cult of people, many of them narcotraffickers, who worship death and on occasion ritually killed adults and children as offerings. On her phone she pulled up an image of a skeletal figure dressed in a cloak with a scythe in hand looking similar to the grim reaper. Her tone heavy and serious, she warned me that devotion to Santa Muerte was growing in Mexico and that with it came violence and criminality.

This figure is called Santa Muerte, a name which translates roughly to Saint Death or Holy Death, depending on who you ask. While this initial introduction to Santa Muerte might have turned most people away from thinking more about Santa Muerte, let alone spending the following summer meeting and interviewing her devotees, I left this conversation fascinated. As a student concentrating in the Comparative Study of Religion, this brief and startling introduction to Santa Muerte left me wondering if there were more to the story than what my host had told me. What really drew people to worshiping a saint who embodies death? Who were the people who worshiped her?

Later that evening, I pulled up the Wikipedia page on Santa Muerte and was surprised to find a section specifically on queer devotion to Santa Muerte. How could it be that the apparently violent and criminal Santa Muerte my host had described also had a large queer following? Was there more to the story of devotion to Santa Muerte than what my host had described?

If my host’s startling description of a violent cult worshiping death is what originally caught my attention, it was queer devotion to Santa Muerte that sustained my interest. Questions at the intersection of queerness and faith had been central to my interest in the study of religion. As a queer person myself who has been a member of religious communities that marginalized queer identities and pushed queer people out of leadership, I abandoned these communities to intentionally seek out queer-affirming faith-based communities. I am intrigued by how people negotiate queerness within religious spaces and how people understand the intersection of these two identities. And so, these questions about Santa Muerte lingered in the back of my mind as I left Mexico City and returned to campus to start junior year.

As deadlines for thesis funding applications drew nearer and I searched for a meaningful research topic, these questions about queer devotion to Santa Muerte resurfaced, and I learned about a community of devotees to Santa Muerte in Queens, New York led by Arely Vázquez, a transgender woman originally from Mexico, who held regular worship services and organized an annual weekend-long celebration to Santa Muerte. I was eager to capture what everyday devotion to Santa Muerte looked like in this Spanish-speaking community of devotees composed mostly of working class immigrants from Mexico with a particular focus on Vázquez and other queer devotees.

I looked into coverage of Santa Muerte in media and academia, discovering that her narcotrafficking following was sensationalized. While this segment of her devotees did sometimes inflict violence in her honor, most followers were women, poor people and queer people—a fact the media and academia generally overlooked. I sought to complicate the narrative that Santa Muerte was only a narcosaint and explore ordinary devotion to Santa Muerte.

One of the most surprising aspects of my research was just how little many of these devotees seemed to think about how queerness impacted their devotion to Santa Muerte. This is not to say that my interviewees never thought about this, but for many there was no need to justify the integration of their queer and religious beliefs. There was little to no need to justify why Santa Muerte would bless queer relationships or why a trans woman should be respected as the leader of this community of devotees.

Vázquez welcoming devotees during the opening ceremony of a weekend long celebration to Santa Muerte that attracts devotees from across the United States.

The equalizing power of veneration to Santa Muerte, as the personification of death, is that death is something none of us can avoid. As a result, her devotees often see her as an amoral figure who will grant requests and protect people without moral judgment about the request or the devotees. This is often cited as an explanation for why Santa Muerte has become a popular figure among narcotraffickers whose requests might receive moral judgements from other saints or Catholic officials. This belief in her support and protection free from moral judgment makes her appealing to an even wider group of people than narcotraffickers, particularly people such as women, queer people and poor people who have felt pushed out of the Catholic institution . The belief that Santa Muerte, as the arbiter of death, can protect people from death or decide when it is time to die, creates a compelling reason for groups like women and queer people who have been repeatedly subjected to higher levels of violence and marginalization within the Catholic church, the mainstream religious institution in Latin America, to follow Santa Muerte.

Devotion to Santa Muerte is not only a source of protection for many of these devotees but also a space where their voices are uplifted and welcomed without needing to qualify them. Unlike queer people in religious communities that are not queer affirming or have only recently shifted towards being queer affirming, many of the queer devotees I talked to told me they did not have to justify their place as a queer person within this devotional community. The inclusion of queer people, along with other historically marginzalied groups, was built in to the theology surrounding devotion to Santa Muerte.

In some ways, this made my research more challenging. I was hoping to tap into an explicit conversation on the intersection of queerness and devotion to Santa Muerte, but I learned that these conversations were farther and fewer between than I had expected because there was no need to defend queerness and devotion to Santa Muerte.

IMG_6437.HEIC- Altar to Santa Muerte at Vázquez’s altar in Queens New York.

At a Fall 2022 event organized by queer students in response to the Harvard Undergraduate Faith and Action’s DOXA service titled “What’s the Good News for my LGBTQ Neighbor” which encouraged queer people to remain celibate or enter mixed-orientation marriages, queer clergy from the Cambridge area gathered to offer a different perspective affirming the full integration of queerness and religious identities. One pastor from the area spoke about how he used to speak at churches and give a defense of why Christianity is not opposed to queerness. But, tired of constantly giving these defenses of queerness, he started to just be queer and religious. He asked students what it might mean to just be queer in religious spaces rather than constantly defining your right to be there in the first place, to imagine what it might look like to make queerness, queer love, queer gender expression, queer leadership ordinary.

In my time with this community of devotees to Santa Muerte led by Arely Vázquez in Queens, New York, I no longer needed to imagine what this might look like. This summer I had the opportunity to observe a community where queerness was not only accepted, but ordinary.

Vázquez leading a procession of devotees from her public altar to a banquet hall during a weekend long celebration to Santa Muerte in Queens New York.

Breda Page Violette is a senior at Harvard College concentrating in the Comparative Study of Religion. Outside of classes, she spends most of her time working as the Administrative Director at the Harvard Square Homeless Shelter and is passionate about creating a world that uplifts the dignity inherent in all people.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

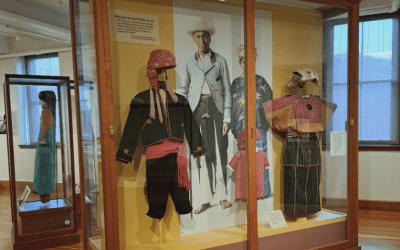

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

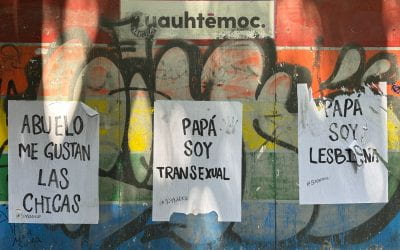

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.