My Queerness is an Asymptote

“Se casaron las brujas” by @Tropiwhat

I was born and raised in north-central Florida—no, not Orlando—spending summers visiting family in Puerto Rico. Although the summers were hot and punctuated by ensuing eczema, I adored going. Tears welled up every time we landed amid the applause of Boricuas returning and spilled over every time I saw the coastline shrink as the plane flew back to a land that was home but did not feel like it. I remember the beaches, celebrating my quince at my grandparents’ house, bathing in bug spray in a fleeting attempt to deter mosquitos, drinking Tres Monjitas orange juice, the song of coquís and, above all, church.

I spent innumerable hours at church as a child and teen. I wholeheartedly believed in Jesus, the Bible and everything I was taught. I witnessed how Christianity, specifically the evangelical Protestant type, can be both a comfort and source of empowering community, especially for Puerto Ricans living in the diaspora. We created our own spaces via church—from support groups for divorced Latina single mothers to Latine Bible Study gatherings. Churches in the United States, despite their pitfalls, can unite and uplift Puerto Ricans and other Latines far from home.

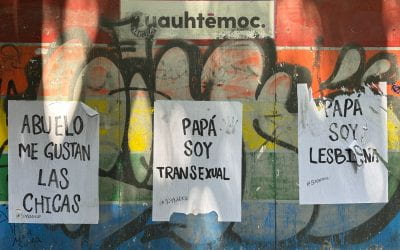

But I want better for us. As I became aware of my queerness and other facets of my identity, I began to view church and religion through a different lens. I do not wish to see our communities fractured by religious fanaticism or solely dependent on Christian institutions for support. It is difficult to leave these insular congregations when it appears there is no other recourse. This can create a toxic loop of dependency and cult-like thinking. I believe people are at liberty to subscribe to whatever resonates most with them as long as they do not inflict harm. I do not believe religious people are evil. Their beliefs, however, can harm others—including and sometimes in particular those within their own religious faction. I resent the version of evangelical Christianity that was relentlessly spoon-fed to me, mutilating my perception of queerness in a seemingly irrevocable way. I mourn the difficulty of disentangling my Christian upbringing from my Puerto Rican identity, memories in Puerto Rico and my own queerness.

I wish the people around me, especially the adults, had critically engaged with their own actions and beliefs before telling me—at as early as 12 years old and usually unprompted—that being “in relations with women” is a sin, that being queer is a choice and a temptation from the Devil, and that homosexuality is something God can “cure.” When the Covid-19 pandemic began in 2020, I, like so many other college students, was obligated to evacuate my campus in New York City and go back home. I dreamt my first nightmare in years three nights after I returned. In the dream, I came out to a family member. Suddenly they were yelling and I was pushed to the ground. Before their fist could meet my cheek, I was awoken by the sound of my own gasp as I screamed “No!”.

A year later, when I was confronted with skepticism over my sexuality during the ongoing pandemic, meaning I had no other place to run to or hide in, I had no choice but to come out as bisexual—a label of which I was unsure but felt I needed to offer to placate others. I was met with statements asserting my queerness stems from having grown up outside of Puerto Rico in a secular country—something I find astonishingly ironic given the United States, especially the Bible Belt, are predominantly Christian—and that this “lifestyle” is, at most, temporary and a divinely ordained test of my faith. At least it was an emotional punch and not a physical one. When I compare childhood conversations to the ones I encountered after coming out, I find they revolve around the same diagnoses. “You are going to hell.” “You are living in sin.” “You are far away from God.” It is as if the Christian adults around me are in a state of arrested development. The monologue has not changed—even more than 15 years later.

Being separated from my extended family by an entire ocean augments the sting and severity of their anti-queer ideology. I cannot spend Christmas with my cousins, share the same meals or have a close relationship with my grandparents because of the distance. Perhaps my family will never consider a different paradigm. They have adhered to an ideology justified by Christianity, or a sect of it, for generations. I am not sure I could ever persuade them to change their minds, although a piece of me will invariably yearn to do so. While I understand that letting go of decades-long indoctrination is painfully onerous and accompanied by potential losses to identity and community, I cannot accept the fact that the people who have seen me grow up and, allegedly, loved me unconditionally espouse queerphobia so carelessly. Between a pious belief and an action resides a choice. Instead of choosing to open themselves to a world of possibilities, my loved ones have chosen to condemn and ostracize queer people for supposed eternal salvation. They claim to be doing this for my own salvation. And at the same time, contend they must do this because God will ask them how they mitigated the sin of homosexuality on judgment day. When confronted with this reasoning, another question arises: Who and what are they truly serving?

Christianity—when framed abstractly and outside of its institutionalization—could be considered radical. Christianity, however, has not existed in a vacuum and its adherents must reckon with this reality. Christianity is not indigenous to Puerto Rico. It was originally a colonialist export used to justify genocide and conquest. The religion itself is rooted in a gospel of expansionism; of taking the word of God to all corners of the Earth with the moral imperative of “saving” every creature. Because of its imposition, central philosophy and enduring catastrophic consequences, I cannot divorce Christianity and colonialism from the abhorrent attacks on the lives of queer people in Puerto Rico and beyond. The effects of centuries-long Spanish colonization and ongoing United States occupation (i.e. lack of infrastructure, extractivist and dependency economics, lack of career growth, etc.) have forced my parents and countless other Boricuas to leave. I, like millions of Puerto Ricans, long to be in the archipelago, but cannot due to socioeconomic limitations. Concurrently, I know that if I ever return permanently, I will be surrounded by a family who may never completely accept my queerness because of their Christian identity. My sexual orientation, something so intimately mine and immutable, has been debated publicly and made out to be incompatible with my heritage, something I cannot and would not change.

Campamento Morton in Puerto Rico. Credit: Campamento Morton Facebook

Although I lament, to an extent, the once-close relationship I had to most of my family both in and outside of Puerto Rico, what I long for most is a proximity to my heritage. I feel it will take years and an intentional effort to cultivate a connection between my queerness and Boricuaness. Christianity barred me from secular Puerto Rican popular culture. Most, if not all, activities that did not revolve around God or church were deemed sinful. These systems of oppression, in conjunction with many others, propagate the racist settler-colonialist argument that anything derived from traditions outside of modern Europe and/or Christianity is sinful. This rhetoric, deployed by a large portion of the Christian community in the archipelago and diaspora, excluded me from experiencing connections to a place from which I already felt partially disconnected due to my Floridian upbringing. Coupled with Christianity-endorsed queerphobia, my Boricuaness feels imaginary, untethered, rife for self-inflicted gaslighting. My family has given me the impression that my sexuality is a product manufactured by the “end times” (the period of time leading up to the Second Coming of Christ, or the Rapture) and characteristically estadounidense. I have no frame of reference, no queer Puerto Rican women from before my time, in whose existence I can find consolation and the assurance that I am not some zeitgeisty anomaly of the 21st century, but rather one of many queer Puerto Rican women spanning centuries.

Recently, particularly within the context of Villano Antillano and Young Miko’s rise to fame, I have begun to learn more about Puerto Rican queer cultures and communities. We have always been here and we will always be here. What I have seen queer people construct, against all odds, is what numerous churches have failed to create with far more capital, access and social approval. Queer people have created collectives rooted in mutual aid and community-centered spaces despite insufficient resources and overwhelming discrimination. I do not believe in heaven or hell, but I pity Christians who have created hell on earth because they cannot fathom unconditional romantic love existing beyond a relationship between a cisgender man and woman. They may sincerely believe posting Instagram Reels of people claiming the demon Beezlebub was exorcized out of a supposedly ex-queer person is fulfilling God’s will. They may sincerely believe reciting condemnations as if they were prayers is a show of faith. They may die sincerely believing they have carried out God’s will when all they have done is deny themselves and others the gifts of joy, family bonds, community and love. If what my family and others have told me is true and I am on a bullet train to Satan’s headquarters, I prefer hell over a heaven full of bigots.

I hope someday Christians harboring anti-queer convictions understand how they contribute to a machista, heteronormative Puerto Rican society that has, at its deplorable extremes, led to the murder of queer people. I hope they understand the gravity of their words and actions even if they fall short of murder. I hope the realization of how much pain they have caused does not crush them. It would certainly destroy me. I simultaneously recognize the systemic factors that lead large swathes of people to condone queerphobia and seek to hold those individuals accountable for their actions—primarily the adults. Above all, I pray for the fall of the christo-colonial project that continues to subjugate, martyrize and divide Puerto Ricans in a manner that only benefits the pocketbooks and political interests of a few.

Though my queerness, gender and Puerto Rican identity have presented challenges, I still possess the privileges of a cis white woman because of my appearance. As such, I have been sheltered from experiencing forms of violence originating from systemic oppression that targets multiple identities and their intersections. I recognize my experiences are not entirely universal and I do not wish to speak on behalf of all queer people. I am committed to ceding space, redistributing wealth and uplifting other voices to achieve collective liberation. I am especially grateful for the collective of people who have supported me throughout my life. Without friendship, love and my siblings—my first experience of unconditional love—I would not be alive. I could have died a literal and figurative death; one in which you reluctantly drift through a life others have imposed, hoping one day soon becomes your last.

Despite everything, I have lived a life. I have remained steadfast in my commitment to being myself. I have often witnessed queer people sacrifice their inalienable right to self expression and authenticity to appease others—a trope of which I have been guilty for more than a decade—or for safety. We all deserve better. I used to believe I should artificially accelerate the process of healing by letting go of resentment for my loved ones’ sake. But why should I? I no longer want to repress my grief and outrage towards incidents of queerphobia and harm. I no longer wish to suppress my agony as I laboriously detangle Christian hate from my cultural background. Each day, the schism between my family and I grows larger, and with it the schism between Puerto Rico and me. I am entitled to grief and frustration. I am entitled to taking the time I need. I am comfortable sitting with these emotions and reactions because I know love abounds within me and around me. Love will rebuild the burned bridges and help decipher which are, lovingly, not worth rebuilding.

My queerness is an asymptote. It is forever reaching, approximating, expanding, but never crossing an axis, never arriving at a final destination. Perhaps other people desire a clearer definition from me—but I cannot give them one. I love whom I love. If a specific label feels right to me someday, I will use it. For now, “queer” works. It spans English and Spanish, the secular and the Christian, the United States and Puerto Rico. For now, “queer” contains the multitudes within me and how they traverse different borders, languages and identities. I am forever arriving, approaching, growing. I am riding this joyful asymptote into the eternity it was meant to span.

Darinelle Merced-Calderon is a Program Coordinator at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. She holds a BA in Economics – Political Science with a Concentration in Hispanic Studies from Columbia University.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.