Sexual (Dis)Identities: Beyond Heteronormativity in Brazil

There was a time in Brazil, long ago, when the division between “heterosexuals” and “homosexuals” seemed sufficient to describe sexual orientation. Today, even an alphabet soup of acronymns isn’t enough to encompass all emerging non-normative sexual identities. The proliferation of terms with identity claims can make us grapple with the infamous problem of representation and representativeness. Given this scenario, a research group dedicated to the study of Ethics, Power and Abjection (EPA), based at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Brazil, decided to compile a glossary of “sexual (dis)identification” terms.

Following on homosexuality, distinctions such as lesbians and gays (LG) were made—even though gay did not always refer to “homosexuals” and its use only became popular in the 1960s. Later, lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender (LGBT) and, more recently, acronyms such as LGBTQIAPN+ (lesbian, gay, bi, trans, queer, intersex, asexual/aromantic/agender, pan/poli, non-binary and more) have emerged. However, both more reactionary critics and allies of these minorities question the spraying of non-normative identifications. People constantly complain about research in the area of gender, sexuality and queer studies because even the most general agreement on how to refer to people’s identities seems to be impossible.

Following on homosexuality, distinctions such as lesbians and gays (LG) were made—even though gay did not always refer to “homosexuals” and its use only became popular in the 1960s. Later, lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender (LGBT) and, more recently, acronyms such as LGBTQIAPN+ (lesbian, gay, bi, trans, queer, intersex, asexual/aromantic/agender, pan/poli, non-binary and more) have emerged. However, both more reactionary critics and allies of these minorities question the spraying of non-normative identifications. People constantly complain about research in the area of gender, sexuality and queer studies because even the most general agreement on how to refer to people’s identities seems to be impossible.

The attempt to encompass all non-normative sexual identities using simply the term queer has also been subject to criticism. Gender and sexuality scholars have pointed out that, as a concept, queer can erase the differences between the various groups represented in acronyms such as LGBTQIAPN+. However, authors such as anthropologist Tom Boellstorff argue that rejecting this term for fear of homogenization could lead to an “individualistic atomism,” an enumerative logic by which each person is identified separately. Between the individualistic and additive logic of acronyms and the risk of homogenizing the differences between non-normative identities, there is also the fact that denominations such as gay and queer are not native to the Latin American context. They reflect processes of North American and European (neo)colonial influence. That is, although the term queer could simplify the nomenclature problem, as ReVista has done in this issue, the cost of such a solution would be succumbing to the use of alien categories in Portuguese or Spanish language.

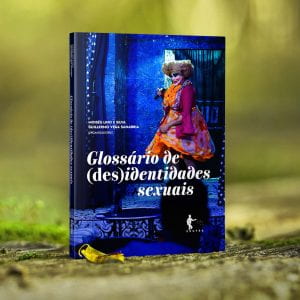

In our recent work, called Glossário de (des)identidades sexuais, we face these analytical, political and methodological challenges through a two-pronged strategy. On the one hand, we respond to the additive logic employed in acronyms (such as LGBTQIAPN+) with a proposal of radicalization ad absurdum. If there is a need to recognize the particularities of each of the emergent non-normative sexual identities, then, they should be analyzed using the logic of a glossary, and not an acronym. On the other hand, objecting to critics who point out that terms such as gay and queer are not “native enough” in Brazil, we argue that all categories normally accepted in identity acronyms should also be questioned in terms of their politics of representation – a lesson we learned, for example, when the feminist movement questioned the universality of very category of “women”. Strictly speaking, all categories of identification, based on gender and sexuality, express, in their own way, the idiosyncrasy of a given collective, an era or a social context. Except, of course, when one intends to elevate any of these categories to the status of “natural,” “normal” or “correct.”

Thinking about contemporary identity issues in an ethnographic way offers an advantage by revealing the complexity of these phenomena in everyday life, beyond what a superficial treatment of theory can sometimes lead to believe. Perhaps this is our modest contribution as anthropologists in this area. Above all, it is about thinking in intensities, degrees, gradations: more or less normative, more or less deviant, more or less collectivist and more or less individualistic. Despite our initial proposal trying to systematize these categories, ethnographic observations suggest that they are not isolated possibilities. In many cases, they intersect and, to different degrees, act in the constitution of different (dis)identities. On the other hand, the marked, deeply situated feature of ethnographic practice also made it difficult for us to reach the level of generalization commonly expected from glossaries and dictionaries. Since the initial conception of the project, the title of “Glossary” was thought of more as an intellectual provocation than, in fact, as an aspiration to produce an exhaustive list of existing (dis)identities and their semantic exhaustion.

Our glossary brings together 29 entries with terms that allude to non-normative identifications, called “(des)identidades.” Most of them go beyond consolidated identities, whether heteronormative or more traditional non-normative ones – such as those in the acronym LGBT. Queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz has argued that minority populations create strategies to resist dominant forces and produce their own truths through these processes of (dis)identification. According to Muñoz, (dis)identities produce a “disempowered” posture that challenges the dominant culture, without intending to create or impose new universal identities, but offering lines of flight for certain minorities not to succumb to normative powers.

Among the most evident strategies in the formation of (dis)identities—strictly speaking, tactics —we highlight the following: 1) resignification (new meanings to words), 2) (re)historization, 3) the production of neologisms (the creation of new words) and 4) the use of verb-noun relations (how practices become nouns and identities). In each one of them, there is a latent potential for appreciation or depreciation, that is, the strategies in themselves are not, a priori, a guarantee that there will be a more positive or negative valuation of a given (des)identidade.

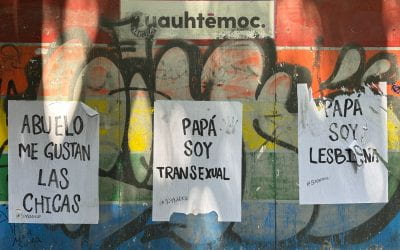

Resignification processes occur with identity categories originally conceived as offensive to different “deviant” groups. For example, among others included in the Glossário, we have: “criança-viada” (“gay-child”) and puto (a naughty male who loves sex). Reframing tactics do not prioritize the creation of new signifiers, on the contrary, they tactically preserve offensive terms and identity categories while actively promoting changes in their meanings. Alteration usually consists of shifting or relocating meaning in a more positive way like has been done in the past with terms such as “queer.” In other cases, however, they are tactics more evidently conceived as practices of militancy, through the political articulation of interest groups. Such movements use various tools to promote reinterpretations, with the Internet being one of the most important contemporary arenas for “semantic clashes” with a large audience.

In other instances, processes of (dis)identification take a markedly historical dimension. In such cases, a broader conceptual apparatus is used, justifying the existence of some categories by pointing to an elsewhere, notably in Africa in the Brazilian case, and to a more or less distant past, invoked in the light of an “ancestry” that allows tracing continuities with terms in the present. In our glossary, some examples are adé (a sexual identity related to Afro-Brazilian religions), cafuçu (men considered atrractive in original refence to racial mixture in Brazil) and mati (used mainly by Black queer women in connection to a slavery past in the Caribbean). This movement of (re)historicization is important not only because it promotes identities previously erased by oppression and repression, but, above all, because it reveals the complex entanglements between ethnic identity, race, gender and sexuality in a more synchronic perspective.

Some (dis)identities have also been associated with neologisms—focused on the invention of new identity terms. Tactics of this type expand the possibilities for subjectivation in certain groups. This is what happens, for example, with Brazilian terms such as bicha-boy, poliamorista and saficrente. Most neologisms discussed in our Glossário arise from combinations of terms. (Dis)identities such as bicha-boy (fag + boy), for example, combine, in a new term, other identities (more or less stable in themselves) to produce (dis)identifications.

Finally, we highlight ways of (dis)identifying that are based on the productive use of verb-noun relations, that is, (dis)identities directly derived from certain actions, practices and performances. This tactic reflects an established discussion in the literature, for example, in the debate presented by Michel Foucault on the historical consolidation of the category of “homosexual” as an identity, a noun and no longer in reference to sexual acts, something that can be performed between people of the same sex. In the light of this “substantivation” process, we have (dis)identities such as escort, camgirl and drag queen, for example, which derive, respectively, from well-known practices such as “accompanying,” “showing oneself via camera” and “doing drag.”

Although many (dis)identities can be considered non-normative, such constructions are indeed not devoid of norms. However, there is an important difference between systems of norms that operate in a group because members adhere to them, that is, identify with the group’s requirements for enjoying a certain identity, and those cases in which identity norms prescribe behaviors and generate a type of demand on people outside the group. Non-normative identities would be those that do not impose their internal identity norms as universal values and, on the contrary, tend to be considered subversive, dirty or dangerous by defenders of more normative identities. They can be considered, non-normative in this sense and manifestations of what a founder figure in gender studies, Gayle Rubin, would critically term “bad sex.”

In certain cases, however, some (dis)identities have more normative tendencies than others. In the organization of the glossary, in fact, we are faced with a certain contradiction. We assumed that the term (dis)identity was quite suggestive and clearly expressed our distance from a prescriptive view of sexuality. We imagined that when talking about (dis)identities we would focus on processes of subjectivation that are difficult to fit into rigid categories, without failing, therefore, to perceive gender, sexuality and emotions as observable forms of the social construction of the individuals. From this point of view, our tendency was to treat all the terms to which the entries in the glossary refer, without exception, as productions that revealed much more about the people who articulate them, their social and cultural contexts, than about sexuality itself.

However, some interlocutors in the research that gave rise to the Glossário (sometimes also the authors of the entries) had a genuine interest in establishing more stable identifications. They sought to differentiate themselves and be recognized through the terms that best served this purpose. Parallels can be made here with theories of ethnicity that emphasize the political character of identifications and have the self-attribution of identities as their central element. This emphasizes the relational dimension of these phenomena. Several studies on ethnicity lead to the understanding that identity is constructed in a situational and contrasting manner. This applies to the production of religious, ethnic or sexual identities, in which the creation of differences and classification systems is central, resulting in distinctive signs that make sense as identities are confronted.

Militant spirit sometimes manifests itself with force, possibly following what postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak calls “strategic essentialism.” However, it is important not to naturalize the militant attitude that publicly claims a specific identity, but to consider that there are spaces in which affirmative discourses about homosexual and similar identities are almost non-existent. In certain situations, physical survival and social integration depend on people’s ability to remain incognito, avoiding assuming or naming certain identities. In the glossary, we find both strongly self-assertive claims of new identities with aspirations for public recognition and expressions of (dis)identity that value secrecy, anonymity and the desire not to be recognized. Furthermore, some (dis)identities, such as those of swingers and polyamorists, incorporate conventional elements and traditional values regarding with whom, how and when sex is possible, and can be as moralizing as more normative sexual identities.

As new words, concepts and practices emerge in this horizon of meaning, it is necessary to pay attention to the predicaments of “individualistic atomism.” Arguments about (dis)identities are sometimes based on oppositions, in such a way that some terms only make sense in contrast to others. For example, sleeping around (puto) contrasts with romance and the antithesis of polyamory is “compulsory monogamy.” Here, the (dis)identity is literal, because, along with identity claims, we also find expectations about what one is not, say, monogamous or romantic. These oppositions coexist with (dis)identities that challenge and assert themselves as “dissidents,” although many of them still transit between traditional notions of masculinity and femininity, which may, in some cases, reinforce some binarism. Despite criticisms of binarism, its logic remains an influential explanatory resource.

The definitions that we offer in our glossary are contextual in an open sense, dependent on the continuous relationships established between the authors and their interlocutors over a time that is not stable. Thus, we recognize that if the same entries were written by other people, the results could be quite different. In line with the aspirations of (dis)identified subjects, our glossary does not claim universal truths. Nonetheless, we aim for the book to be read as a collection that goes beyond the editorial sense, as an entanglement of ethnographic evidence about the existence of a collectivity (dis)identified with the logic of the most well-known and established acronyms of sexual identification.

Guillermo Vega Sanabria is an Associate Professor of Anthropological Theory at The Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), in Brazil. He is the convenor of the Education, Science and Technology Commission for the Brazilian Association of Anthropology.

Moisés Lino e Silva is the author of Minoritarian Liberalism: A Travesti Life in a Brazilian Favela (Chicago, 2022). He is a Visiting Associate Professor in WGS at Harvard University (2023), and an Associate Professor of Anthropological Theory at The Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), in Brazil.

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.