My Time

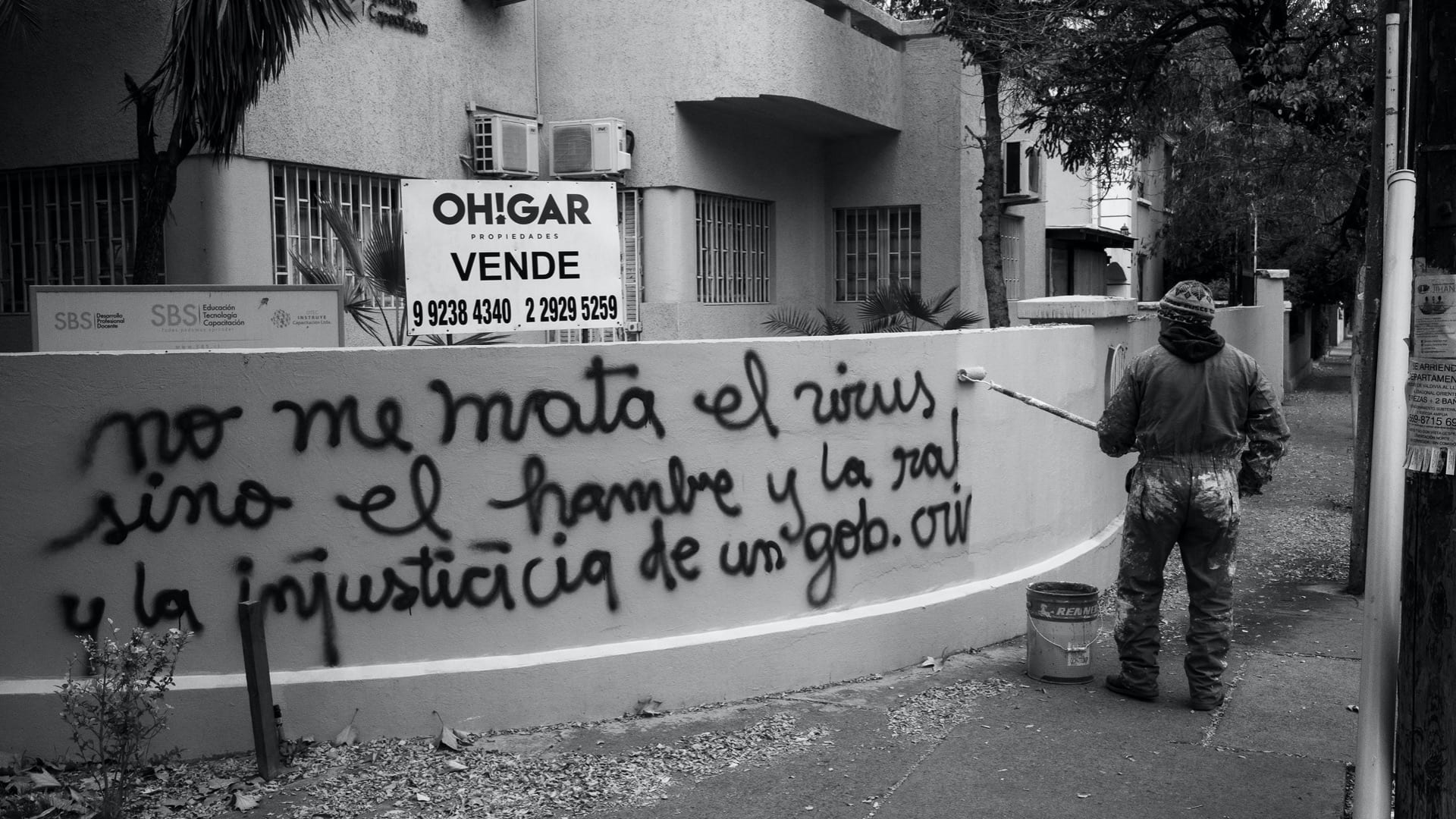

The three top photos included in this article are from the digital exhibition “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America,” curated in collaboration with ReVista and the Art, Culture, and Film program at Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS.)

The exhibition, based on an Open Call for Photography launched in July 2020, aims to create a critical visual record of our unprecedented times so they can be remembered by future generations. 2020 will be remembered as a watershed year in which a pandemic laid bare the inequalities and fissures within our society. It has also underscored the importance of living and participating in communities even while experiencing the pandemic in isolation. The exhibition seeks to promote a regional perspective from Latin America and the Caribbean of the collective isolation imposed by Covid-19.

A few days before the mandatory quarantine was declared in Chile, I thought it was best to leave Santiago. We knew the situation was very serious, but we did not know how the pandemic would actually be experienced. I know how to live with an earthquake; as a historian, I know about the effect of the ancient plagues. But a pandemic, and especially a global one, was so very unknown. I also didn’t know that no one else knew. I didn’t prepare anything to leave. I just took my medical kit (at my age, medicines are indispensable) and my computer, even more indispensable. That was all. However, and even now I don’t know how, my intuition was this would be very long. So I packed all my research material, three years of archives from remote places in the Chilean south, Berlin, Paris and long research trips to Rome. I set off on the already crowded highways. Could it be that all of us were getting out of Santiago? As if one could really get out of the pandemic! Like me, they were going to shelter themselves.

I have a small house on a family property very close to Santiago. It is in a beautiful valley with just houses on the side of the road and many small stores that all sell the same things. In the valley, there are no coffee beans. That’s the only staple I brought with me. I could leave behind the trips to the supermarket, filled with frenetic shoppers. The panic of others produces panic in me. I was not afraid of the virus. I’m from the countryside and I spent my childhood around cow and horse dung, fruit that we never washed, stuck in ditches. My parents considered that was the best vaccine and life has proven them right. To keep myself isolated was not a great effort. I had to set up “rural Internet,” which resulted magnificent because the signal frequently failed.

Installed in this strange experience, the beginning came from the news. It was a dull fear. Our health system struggled to avoid having “the last bed taken,” a reality that came closer and closer. Behind these images of the world’s great cities in solitude and silence appeared the indisputable text that the world was changing. I have lived through this solitude and silence only once before: September 11, 2001, in Washington DC. The night before, I had taken the train from New York, the last night. The next afternoon I spent walking with my sister every place that security permitted. And it was a lot of walking. In this silence and solitude not shown on television, I felt that if we children of the Cold War felt that its end was our victory and the almost definitive salvation of democracy, terrorist fundamentalism showed us other forms of violence that paved the way to new wars and new discriminatory behaviors. The silence. I took the plane back to Chile the first day Reagan Airport reopened. No one spoke a word. The lines of passengers, judging by their clothing, appeared to be Arabs. We foreigners all appeared suspicious and we will keep on appearing that way in this so beloved country.

Returning to today’s situation, the syndrome of the last bed was accompanied the syndrome of the last job. The economy was collapsing and unemployment increasing. Serious economists tell us that it will take 15 years to recover the pre-Covid level, which was not very good either. We were suffering not only with the victims, but with this devastating poverty and the phantom of returning to be as poor as we have been historically, rather than emerging as a tenuous middle-class country. I remembered how, as a quite young woman, I experienced that other September 11, that of 1973: a failure. A failure that for me was not the demise of a popular revolution, but the destruction of Chilean democracy. On September 11, a project was buried that had possibly begun in 1964 with a democratic election, of an inclusive modernization in the context of a genuine participatory democracy.

I was shaped intellectually in the dictatorship. I do not have to comment on that horror. The conquest of democracy and the transition were really difficult. All of us are generals after the battle, but what is certain is that those who criticized the transition at the end of the 90s did so with unprecedented disdain and maximalism. But at the end of the day, it was an attack on politics in and of itself, that is, the necessity to lead and negotiate. If politics does not negotiate, then the most probable thing is that it is a dictatorship. Later, a significant sector of the Concertacion—the alliance of left-leaning and centrist political parties—began to vilify their own works, ashamed that the youthful students mobilized in 2011 denounced them as “neoliberals” and continuers of the dictatorship. The lack of confidence in institutions, as happened all over the world, grew and grew; economic development was stagnating and this enormous population that had left poverty behind, and these new middle classes, rightfully felt that they had done their part with great individual effort and that the state had not kept up its end of the bargain with first-rate public services. Discontent was evident. Politicians and analysts seem to have been ignoring the evident not to have anticipated the social explosion of October 18, 2019. But that is a fallacy. The ruptures were not forseeable. There are moments when structure and context converge and they acquire their own dynamics. I was thinking about all this as I drove from the city to the countryside.

The explosion of October 18 was made up of very diverse groups. The million and a half Santiago residents that took to the streets are distinct from the youthful groups who persisted in violence that in turn had distinct profiles. One more political and the other of vandalism. But they shared a visceral rejection of all forms of power. I live squarely in the “zero zone.” I could see how the protesters operated in a more organic form than it appeared, but in a horizontal fashion, without leadership. The police officers—known in Chile as “carabineros”—showed not only a gross strategic ignorance but, what was even worse, returned to a violation of human rights. Finally, there was an important political channeling through Parliament for a new constitution. These youth—it was learned that the majority of them were highly educated—cried out with angry slogans against the last decades. “It’s not 30 pesos [the subway hike that set off the explosion]; it’s 30 years.”

If at the tender age of 18, I had felt the collective failure of democracy’s destruction, in October, I felt the personl defeat of my generation, that had fought against the dictatorship and had participated in democratic reconstruction. At the end, it was a cultural defeat. “Neoliberalism” was a concept that marked the continuity between dictatorship and democracy. My God, this was a blow!

And now the pandemic. While the weeks passed, reflections about how the world would change proliferated and I followed them with genuine interest. I couldn’t stop thinking about the black plague. Between 30 and 50% of the European and Asian population died then. Today the deaths have not reached 1%. And the world feels each death as its own. Life matters a lot more to us now than in those times when it was easier to die than live. The Black Plague was also one of the causes of the end of feudalism. The analogy gives me a certain optimism. Not because capitalism is going to fall, but because the illustrated logic of progress, that of time only as mechanical, in which “more” is always equivalent to “better” has entered into a crisis, made evident by the pandemic.

One morning I went to visit my neighbor Claudio Carrasco. His father had received a parcel of land during the agrarian reform. He had inherited two hectares that he worked with care. He was a talented carpenter. He had a mare, Lolita, he loaned me now and then. As he brushed her down, he commented to me how life had changed. “People behave themselves better now in the parties and birthday festivities and on Sundays,” he told me. “They drink less and because there are fewer people, we converse more now.” I think he caught my look, which was somewhere between surprised and moved. “People converse more now?” I asked him. He kept brushing his mare, making her beautiful, and replied, “There’s more time.”

That night I had to participate in a television interview. The question about the significance of the pandemic for future was obvious. Breaking the silence that was a mixture of defeat and fear, I answered with a voice that was more clear than strong:

“Time, the value of time, the sense of time.”

Mi tiempo

Por Sol Serrano

Las tres primeras fotos utilizadas en este artículo provienen de la exposición digital “Documentando el impacto de Covid-19 a través de la fotografía: Aislamiento colectivo en Latinoamérica,” curada por ReVista y el Art, Culture, and Film program del David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS) de Harvard.

La exposición, resultado de un concurso de fotografía anunciado en Julio 2020, busca crear un registro visual de estos tiempos sin precedentes y contribuir a nuestra futura memoria histórica. 2020 será recordado como una año decisivo en el que una pandemia dejó al descubierto las desigualdades y fisuras dentro de nuestra sociedad y la relevancia de vivir y participar de la vida en comunidad incluso mientras se vive la pandemia de forma aislada. La muestra procura promover una perspectiva regional del aislamiento colectivo impuesto por el Covid-19 desde América Latina y el Caribe.

Pocos días antes de que se declarara la cuarentena obligatoria, pensé que era mejor partir Santiago. Sabíamos que era grave, pero no sabíamos cómo se vive una pandemia. Se vivir un terremoto; como historiadora, se cómo fueron las pestes antiguas. Pero una pandemia, y más encima global era tan, tan desconocido. Tampoco sabía que nadie lo sabía. No prepare nada para partir. Solo mi botiquín (a mi edad los remedios son indispensables) y mi computador, más indispensable aun. Eso era todo. Sin embargo, hasta ahora no sé porque, tuve la intuición de que sería largo. Entonces empaque todo el material de mi investigación, tres años de archivos en remotos lugares del sur de Chile, Berlín, Paris y largas estadías en Roma. Emprendí camino por carreteras ya atestadas. ¿Estábamos todos arrancando de Santiago? ¡Como si de esto se pudiera arrancar de la pandemia! Iban a guarecerse, como yo.

Tengo una pequeña casa en el campo familiar muy cerca de Santiago. Es un hermoso valle con solo casas en la orilla del camino y muchas pequeñas almacenes que venden todas lo mismo. En el valle no hay café de grano. Fue lo único elemento básico que lleve. Podría saltarme la ida al supermercado, repletos de compradores frenéticos. El pánico ajeno me produce pánico. No le tenía miedo al virus. Soy de campo y pase mi infancia entre bostas de vacas y de caballos, frutas que nunca lavamos, metida en las acequias. Mis padres consideraban que esa era la mejor vacuna y la vida les había dado la razón. Mantenerse aislado no era ningún esfuerzo. Tuve que poner “internet rural” que resulto magnifica porque la señal se cae con frecuencia.

Instalada en esta extraña experiencia, al comienzo arranque de las noticias. Era un miedo sordo. Nuestro sistema de salud luchaba por no llegar al horror de la “última cama” que se acercaba más y más. Detrás de esas imágenes de las grandes ciudades del mundo en soledad y silencio aparecía el texto irrefutable que el mundo cambiaba. Yo había vivido ese silencio y esa soledad una sola vez antes: el 11 de septiembre del 2001 en Washington DC. La noche anterior tome el tren desde Nueva York, su última noche. La tarde siguiente caminaba con mi hermana todo lo que la seguridad nos permitió. Y fue mucho. En ese silencio y en esa soledad que la tv nunca mostro, sentí que si los hijos de la Guerra Fría creíamos que su fin era nuestro triunfo y la salvaguardia casi definitiva de la democracia , el fundamentalismo terrorista nos mostraba otras formas de violencia que le daban alfombra roja a nuevas guerras y a nuevas discriminaciones. El silencio. Tome el avión de vuelta a Chile el primer día que abrió el aeropuerto de Reagan. Nadie hablaba una palabra. Las colas de pasajeros, por sus indumentarias, parecían ser árabes. Todos extranjeros parecíamos sospechosos y lo seguimos pareciendo en ese país tan querido.

Regresando a la situación de hoy, junto al síndrome de la última cama estaba el síndrome del último empleo. La economía se desmoronaba y la cesantía crecía. Economistas serios decían que nos demoraría unos 15 años recuperar el nivel pre-Covid, que no era muy bueno tampoco. Fuimos sufriendo no solo con las victimas sino con la horrorosa pobreza y el fantasma de volver a ser tan pobres como históricamente habíamos sido, en vez de emergir como un país tenuo de clase media. Me volvió aquello que, siendo muy joven, sentí el otro 11 de septiembre, el de 1973: el fracaso. Un fracaso que en lo personal no era el de la revolución popular sino el de la destrucción de la democracia chilena. Allí se enterró un proyecto que había empezado posiblemente con la elección de Eduardo Frei en 1964, de una modernización inclusiva en el marco de una genuina participación democrática.

Me forme intelectualmente en dictadura. Sobre ese horror no tendré que referirme. La conquista de la democracia y la transición fueron realmente difíciles. Todos somos generales después de la batalla, pero lo cierto es que los críticos de la transición a fines de los 90 lo hicieron con un inusitado desdén y maximalismo. Pero fue un ataque finalmente a la política en sí misma, es decir, la necesidad de conducir y negociar. Si la política no tiene que negociar, lo más probable es que sea una dictadura. Luego, un sector no menor de la Concertación—la alianza de partidos izquierdistas y centristas— empezó a denostar su propia obra, avergonzado porque los jóvenes estudiantes movilizados en 2011 les gritaban que eran “neo liberales” y continuadores de la dictadura. La desconfianza hacia las instituciones, como en todas partes, crecía y crecía, el desarrollo económico estaba estancado y esa enorme población que había salido de la pobreza, y esas clases medias nuevas sentían y con razón que ellos habían cumplido su parte del trato con gran esfuerzo individual, pero que el Estado no cumplía el suyo con servicios públicos de calidad. El malestar ya se sabía. Políticos y analistas se toman la cabeza a dos manos de no haber previsto el estallido social del 18 de octubre, 2019. Pero es una falacia. Las rupturas no son previsible. Son momentos en que converge lo estructural y lo coyuntural y que adquieren su dinámica propia. En eso pensaba cuando maneje de la ciudad al campo.

El 18 de octubre comprende muy diversos grupos. El millón y medio de santiaguinos que salió a las calles es diferenciables de los grupos jóvenes que persistieron en una violencia que a su vez tenía distintos perfiles. Uno más político y otro más vandálico. Compartían un rechazo visceral a toda forma de poder. Vivo exactamente en la “zona cero”. Pude ver como operaban de una forma más orgánica de lo que parecía pero horizontal, sin liderazgos. .Carabineros probó no solo una supina ignorancia estratégica sino, lo peor, que volvía a la violación de los derechos humanos. Finalmente, hubo una importante canalización política a través del Parlamento para una nueva constitución. Esos jóvenes –se ha sabido que en su mayoría son bastante educados- voceaban con rabia lemas en contra de las últimas décadas. “No son 30 pesos [el alza del metro que prendió la llama] son 30 años”.

Si a los 18 años había sentido el fracaso colectivo de la destrucción de la democracia, en octubre sentí la derrota personal de mi generación, la que había luchado contra la dictadura y había participado en la reconstrucción democrática. Al final, era una derrota cultural. El “neo liberalismo” era el concepto que marcaba la continuidad entre dictadura y democracia. ¡Dios mío, ese sí que era un puñal!

Y ahora la pandemia. Mientras pasaban las semanas brotaron las reflexiones sobre cuanto cambiaría el mundo y las seguí con genuino interés. No podía dejar de pensar en la Peste Negra. Entonces murió entre un 30 y 50% de la población europea y asiática. Hoy las muertes no llegan al 1%. Y el mundo siente cada muerte como propia. Cuanto más nos importa la vida ahora que en esos tiempos en los cuales era más fácil morir que vivir. La Peste Negra también fue una de las causas del final del feudalismo. La analogía me daba cierto optimismo. No porque fuera a caer el capitalismo sino porque la lógica ilustrada del progreso, la del tiempo solo mecánico, en el que “mas” es siempre sinónimo de “mejor” , había entrado en una crisis que la pandemia hacia evidente.

Una mañana visite a mi vecino Claudio Carrasco. Su padre recibió una parcela durante la reforma agraria. El heredo dos hectáreas que trabaja con esmero. Es un hábil carpintero. Tiene una yegua, Lolita, que me presta de vez en cuando. Mientras la rasqueteaba, me comento como la vida había cambiado. “La gente se porta mejor ahora en las fiestas y los cumpleaños y los domingos, me dijo, se toma menos, y como somos pocos, entonces ahora conversamos”. Creo que capto mi mirada entre asombrada y conmovida. “¿Ahora se conversa más?”, le pregunte. Dudo de su respuesta y mientras seguía con la rasqueta hermoseando a su yegua, solo me dijo: “hay más tiempo”.

Esa noche tenía que participar en un programa de TV. La pregunta sobre el efecto de la pandemia sobre el futuro era obvia. Rompiendo el silencio amalgamado con la derrota y el miedo, respondí con voz más clara que fuerte:

“El tiempo, el valor del tiempo, el sentido del tiempo”.

Sol Serrano, historiadora y ex vicerectora de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, fue 2008-09 Luksic Visiting Scholar en el Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos David Rockefeller de Harvard. Ella fue la primera mujer a ganar el Premio Nacional Chileno de Historia en 2018.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...