The Odalisque in Red Pants

A Museum as National Metaphor

The location, characters and what was about to happen are worthy of a thriller: in a room in the luxurious Hotel Loews in Miami, two supposed art dealers, Pedro Antonio Marcuello Guzmán and María Martha Elisa Ornelas Lazo, waited for some potential art buyers for something huge they had been offering for a while: nothing less than one of the odalisques painted by French artist Henri Matisse, valued at three million dollars. They’ve been offering the artwork in a somewhat discreet fashion for a while, but they haven’t been able to find anyone sufficiently rich, and, at the same time, sufficiently trusting or devoid of scruples, to accept their business proposition. To encounter these dealers like clandestine lovers in a hotel room suggests anything but a normal transaction. The buyers arrived. We do not know what happened in the next few minutes, but it must have been chaotic. Surely, the buyers asked to see the Odalisque with Red Pants. Surely, they studied it closely to make sure it was an original and then, perhaps with a gesture appropriate to Hollywood, showed their FBI credentials, revealed themselves as undercover agents and arrested the two dealers.

That was the climax of a story with many other cinematographic moments. To commission a forgery of the Odalisque with Red Pants good enough to keep the curators of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas from immediately discovering the robbery; to find the precise moment to remove the true canvas and substitute the forgery, to smuggle the work out of Venezuela and somehow introduce it into the European market, must have taken months of planning and suggests a wide network of accomplices. Although there has already been at least one long article about this heist, sooner or later, some novelist or screenwriter is going to put the plot to good use.

This incident serves as a starting point to portray not only the fate of Venezuelan museums during the past half century, but in general what happened with a country that had a museum unimaginable in Latin America at the beginning of the 1970’s, and that 40 years later, one of its emblematic works of art would be stolen in the context of a decline that, at its lowest point, practically resulted in the museum’s technical closure. What happened with the Odalisque and with the Museum of Contemporary Art is a metaphor for a Venezuela that believed that a future of development and prosperity was at hand, maybe by the year 2000, and later, when at last, the 21st century arrived, it felt as if that future had been left behind or had never come at all. Let’s take a glimpse at this bewildering situation through the lens of the museum and its promoter, Sofía Imber (1924-2017).

Sofía Imber, Romanian-born Venezuelan journalist and the founder of the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas. Photo courtesy of Macsi.org.

The Future That Wasn’t

In 1973, with the eruption of the energy crisis, oil prices began climbing and, in eight years, tripled. In few places in the world did it have as far-reaching and long-lasting consequences as in Venezuela. The country, which had for several decades been the first oil exporter and second producer in the world, saw on the horizon a boom of petrodollars greater than in the 1920s and during the 1956 Suez Canal crisis, indeed a boom greater than the dreams of the most optimistic Venezuelans. So much money arrived like a tornado on the horizon that the sensation was “now or never.” Carlos Andrés Pérez, the Social Democrat candidate who swept the presidential elections, named his project “the Great Venezuela,” foreseeing a developed country, owner of its resources (the oil and iron industries were in the hands of foreigners, most of them U.S. companies, leading him to propose nationalization.) According to his plans, these dreams would be realized by the year 2000.

Besides the petrodollars, other reasons for optimism existed: Venezuela had been a democratic country for 15 years with four consecutive free presidential elections, something that had never been experienced before in its history; the last great civil war had ended 70 years earlier, in 1903; in spite of the efforts of the Communist bloc to support Venezuelan guerrillas, and all the military and terrorist action these groups carried out, they were defeated in six years and did not alter the country’s progress. In the Latin American panorama, Venezuela was an example of stability, liberty and progressive politics. No one was denying a plethora of problems and contradictions, but compared to the region and to the country itself before the 1930’s, the balance resulted favorable. No wonder Venezuelans were not very nostalgic about the past.

If anything characterized those years, it was the accelerated and sometimes violent change in the urban landscape. Everywhere possible, the state and private investors tore down colonial architecture, seen as a sign of backwardness: in many sites, the most emblematic dwellings were two centuries old, and those who dwelled in such buildings were looked down upon. Today we see it quite differently, but from 1940 to the mid-80s, as in many European cities in the 19th century, to destroy the historical past to construct something new was a process many have compared to a palimpsest—those pieces of parchment in the Middle Ages in which writing was always erased to make room for writing something new. Caracas was transformed into a great laboratory for urban and architectural modernity, but the rest of the cities, each of them at their own scale, did what they could in that respect. If something could bring the future closer, it was architecture—which created the illusion in 1950 or 1970 of being in the imagined space of the year 2000.

The urbanistic complex of Central Park is the epitome of that dream. As José Balza wrote ecstatically in a 1982 chronicle, in effect, with this architectural feat, “everything belongs to the year 2000.” That is, 2000, as imagined in 1982. Although similar projects had been tried, nothing had been done on this scale. An entire urbanization from the 1930s was demolished (in Caracas of those days, 40 years was considered old for an urbanization) and a group of skyscrapers for the growing professional middle class was constructed with all the necessary services to create an ultra-modern city within the city. Two office towers, destined to be the tallest in South America.The project was begun in 1970, before the oil boom. As a matter of fact, the price of oil was going down at the time. If under these circumstances, a project like this could be undertaken, it is easy to imagine how things would develop when income from one year to another was fourfold.

Inside the Central Park complex, one could find everything or almost everything. Movie theatres, supermarkets, an abundance of shops and restaurants, a convention center. The only thing that was missing was a museum of modern art, or at least that’s what some personalities of the Caracas cultural milieu thought. Since 1917, the city had a Museum of Fine Arts that was in the process of expanding and modernizing. But its name clearly indicated what could be found in its exhibition halls: primarily 19th-century beaux arts grand masters. The new city literally being erected on the ruins of the old one needed something more in tune with the times.

Thus, in 1971 the Parque Central planners thought about a Museum of Modern Art, soon changed in name to Contemporary Art, perhaps with the same sense of era like that of beaux arts: the contemporary, a new history period beginning in 1960 that had erupted in Western thinking. The intellectual elite was reading the English historian Geoffrey Barraclough, who declared the landing of man on the moon and recent social upheavals were the beginning of a new historical era, and they were very certain (dangerously certain) and proud (dangerously proud) of beginning that new era. This new period was to be made felt in its artistic forms within Central Park, the heart of the new city, of the new Venezuela. In 1973, a new mandatory subject was assigned in all the high schools: the Contemporary History of Venezuela. And likewise, the Museum of Contemporary Art Foundation was created, headed by journalist Sofía Imber. If anyone could get us to that year 2000, it would be her.

Sculptures decorating the gardens that lead to the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

Carlos and Sofía

In the intellectual world, Carlos Rangel and Sofía Imber were the couple of the moment. Loved and hated with equal intensity. Their morning talk show, broadcast since 1969, transformed Venezuelan television at the time. For more than 30 years, no politician or artist was considered sufficiently renowned, if they had not been on the show. Both were already very famous in the world of journalism, when their romance became a subject of abundant gossip. They both left their respective partners (in the case of Sofía, no one less than the famous writer Guillermo Meneses), to live together. Sofía, whose irreverent chronicles (for years, she had a much-read column in El Nacional called “I, the Uncomprising One”), already much discussed, became the fodder for conversation.

But Caracas society very quickly got used to seeing Carlos and Sofía together and forgot about gossip. Leftist intellectuals—and the great majority of intellectuals were leftist—did not forgive as easily because in their eyes the couple had committed a much greater sin than their romance: not only were they not Communists, but they were the clearest and most prominent anti-Communist voices in the intellectual world. As Carlos and Sofía saw it, the country was basically opposed to the guerrilla and took as their idols two of the most fervent enemies of the left, Romulo Betancourt and Carlos Andrés Pérez; this was not a problem for the average Venezuelan. But in the world of arts, literature, the universities, the situation was diametrically opposed. In 1976, Carlos Rangel published Del Buen Salvaje al Buen Revolucionario [From Good Savage to Good Revolutionary], with a prologue by the famous French philosopher Jean-François Revel. The book immediately became a Latin American best seller. It became an anti-[Eduardo] Galeano tome, putting the blame for the problems in the region on Latin Americans themselves, unlike Galeano, who blamed U.S. imperialism.

Even worse, Sofía was a “White Russian.” Although she was only six years old when she arrived in Venezuela with her parents and always felt her roots in Venezuela, in the beginning, she was seen as a Russian and dubbed “the little Russian,” a term both of affection and distancing. In reality, she was not a Russian, but from Moldavia, but since the country had only become independent a short time before she was born and previously was part of the Russian empire, then Rumania and finally, the Soviet Union again, the term “Russian” was not that far off-base: if she had remained in Moldovia, she would have been a Soviet citizen for a great part of her life. However, practically no one in Venezuela knew of the existence of a country called Moldovia. Fleeing political turmoil and the pogroms (the Imbers were Jewish), her parents embarked for the faraway and unknown Venezuela. Like so many other immigrants from central and Eastern Europe, they were successful, so much so that their daughters made history. The eldest daughter, Lya Imber became the first woman to graduate medical school in Venezuela. Sofía preferred journalism.

Her biography from her journalistic beginnings in the 1940’s until the founding of the museum is the embodiment of modernity in the West. The “little Russian,” who was at first confined to reporting for the social pages, appropriate for a señorita, especially a refined European señorita, over time became one of the most important voices of cultural and political journalism in the country. Then came her discovery of modern art and the birth of the idea of the museum. All the modernization she had experienced in her own life was channeled into this institutional and transcendent project.

A sculpture by Alexander Calder hanging in the vaults of the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

The Museum of Caracas is Born in Paris

The Museum of Contemporary Art’s amazing collection cannot be separated from its immediate predecessor, the University City of Caracas, constructed between 1942 and 1954 (although many of its parts were finished afterwards). Designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva, it is, along with Brasilia, probably the most important touchstone of 20th-century modern architecture in Latin America. UNESCO declared it Patrimony of Humanity.

Several fortunate circumstances aligned around the design and construction of the University City: the ever-expanding state budget, the conviction of all the governments of the era to make the leap to the future, and therefore to prioritize the country’s main university, and last, but not least, the enormous talent of Villanueva, his deep knowledge of the vanguards of the beginning of the century, as well as his friendship with many of its principal representatives. The result was the “integration of the arts,” which Villanueva achieved with works by Jean Arp, Férnand Léger and Alexander Calder, among many others. It is possible to imagine him at the beginning of the 1950s as the emissary of a faraway and very rich tropical country, as sort of an actual emirate, with an unlimited budget to commission works. And Villanueva was not the only one. Venezuela builders contracted architects, engineers and artists for their projects in quantity—a fact that did not go unnoticed in the media. Venezuelans were quite popular. In this context, the “little Russian” Sofía Imber arrived in Paris with her husband, the much-honored writer Meneses. The circumstances were somewhat polemic: the military dictatorship had appointed him to a diplomatic position—the same military dictatorship that he disparaged in 1948 with his essay on democracy begun three years earlier. And it was not just any position—nothing less than First Secretary of the embassy.

But Meneses is just as irreverent as his young wife, and he had already caused several scandals with his stories in the 1930’s and soon with La Mano junto al muro (The Hand by the Wall), which would be attacked by many, including the church. The work marked a “before” and “after” in Venezuelan literature. Imber and Meneses were very much the self-assured, modern, cultured couple in Paris, which still was viewed in great part as the world capital of the arts. There they met Villanueva, who frequently went back and forth from Venezuela. Sofía, inquisitive and with much time in Paris, met Jean Arp and Henri Laurens through Villanueva. She made friends with Picasso. The Hungarian-French painter Víctor Vasarely became a member of her inner circle, and their close relationship fed a lot of gossip (Sofía insisted that they were only friends, and while she took lovers, he was not one of them, she said).

Gossip apart, the fact is that when the couple returns to Venezuela, Sofía was erudite in modern art with a network of relations that, in a few years, would be enormously useful for the country. As she recounted to her biographer, Diego Arroyo Gil, it was she who, seeing the development of Central Park, proposed the creation of the museum to the president of Centro Simón Bolívar, the construction company spearheading the project. She also asserts that she was responsible for the shift from “modern” to “contemporary.” Both assertions surely have nuances, but there seems to be no doubt that she had important participation in both decisions. In one way or another, when in 1973, the Foundation was established and locations chosen within Central Park (spaces that were not initially thought of as a museum and that she gradually took over for other projects), the moment came to look for artwork. She was given a limited budget, surely less than that Villanueva had 20 years earlier, although one that would have been impossible for any other Latin American country in those years: US$60,000. With this, she went to Europe to seek out friends, renew contacts and to buy the best possible artwork.

In a short time, a collection began to arrive in Caracas that everyone viewed with amazement: Duchamp, Kandinsky, Klee, Chagall, Gris, Picasso, a lot of Picasso. In those packages and wrapped works, it seemed, like never before, that the year 2000 was beginning to become reality.

A sculpture by James Mathison in the vaults. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

Sofía’s Museum

The museum—”Sofía’s museum,” as her friends called it—became a reference point throughout Latin America and a source of pride for Venezuela. Caracas residents and those who visited the city could enjoy the ample collection of work by Picasso, Léger, Mondrian, Braque, Miró, Kandinsky, Warhol, among many others, very unusual in the Third World. They could attend workshops and conferences in the museum space and visit its well-stocked library. Respect for Sofía and her capacity to negotiate permitted budgets to acquire artwork even when the economic situation began to go downhill. Her contacts helped her get donations. The now famous Odalisque with Red Pants was purchased in 1981 in the Marlborough Gallery in New York for US$480,000. She acted as always: going to the gallery to see what was new, she saw the painting, somewhat expensive for her budget, but she got the money together in one way or another and bought the painting. With this endeavor, she put together a first-class task force and created workshops, an extraordinary art library and a gift shop and restaurant. She expanded the museum as much as Central Park would permit, reaching 66,000 square feet. In 1990, the museum began to call itself the Sofía Imber Museum of Contemporary Art (MACSI), a homage in life that stirred up polemic.

But increasingly, it was a bubble inside of a Central Park in the midst of a country that had taken a different path. A country that was growing poorer, dirtier, breaking down, withering, losing efficiency. As the year 2000 approached, Central Park demonstrated in every corner, in every hallway, how the promises of the 70’s were not fulfilled. The erstwhile complex to which much of the artistic world of Caracas had moved, was aging and deteriorating like the middle class and the state that administered it. Fountains without water, dark halls, broken elevators, stopped escalators, dirty floors, boutiques and restaurants that had seen better days, frequent stories of robberies, contrasted more and more with a museum that insisted on maintaining itself pristine. The 21st century found Venezuela with 70% poor people and fewer than 10% rich, after having had a large middle class, about 60% in the 1960’s.

That is, in this world that shriveled the rest of Central Park, with these people who had moved to a spot in which “everything belongs to the year 2000,” who now find themselves waiting in line for one of the few working elevators, those boutique owners who struggled not to shut their doors, those government employees, it was impossible not to look askance at this museum with its Picassos, its Warhols, its Matisse…we are not specifically talking about Central Park, but of the entire society that believed that in the year 2000, the country would be modern and prosperous, and instead found it poor and crushed. It was a society that had overwhelmingly voted for Hugo Chávez in the series of elections that gave him full power between 1999 and 2006. A museum so firmly ensconced in the fundamental lines of the country’s development, so organic, so existentially Venezuelan, could not be removed for much time from all this. Parodying Balza a bit, one could say that in the year 2000, in Central Park, everything seemed to be 1970.

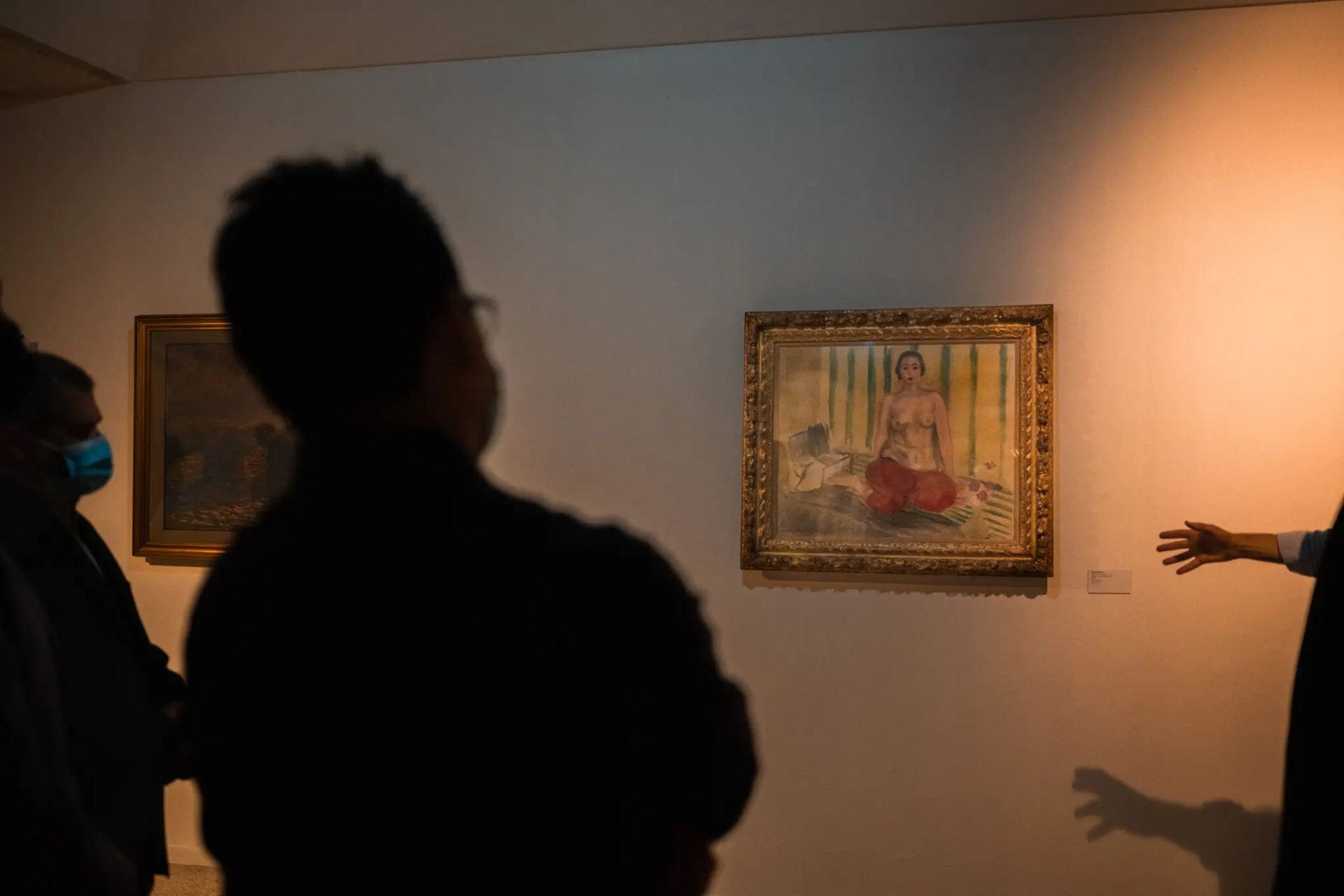

Visitors looking at a Picasso painting shortly after the partial reopening of the museum. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

After the Future

By 2001 Chávez had already taken firm steps to demolish the old regime. The anti-Communist Sofía could hardly survive the change. This emblematic modernizing woman of the “fourth republic,” as the previous regime was dubbed to distinguish it from his “fifth republic,” was one of the many symbols that had to be gotten rid of. Moreover, one must remember that she was always loved and hated with intensity. Naturally, many of those who hated her were those leftwing artists and intellectuals who were now grouped around Chávez. Some of her critics were right, of course: 30 years at the head of a public institution could translate into a type of feud; the name of the museum denoted personalism, which many accused her of in the management of the museum; this idea of “Sofía’s museum” would not necessarily be a virtue. Although personalism and the desire for perpetuity in power very soon became characteristics of Chavismo, in 2001, this was not clear to many, or if it was clear, at any rate, it provided a way to get rid of Sofía.

She was perfectly aware she would have no place in the Chavista state. She was convinced that the moment had come to resign, but Chávez, as he often did, speeded up the process. In his Sunday program on January 21, 2002, he declared, “How difficult is this world of culture! How it has been managed!” immediately charging, “Culture has been made elite, managed by the elites, as Manuel Espinoza has said: a princedom…. Princes, kings, heirs, families, they take charge of institutions, of premises that have cost the state thousands of millions of bolivars [the Venezuelan currency].” Then he fired her. Her dismissal was applauded by many, with smiles of satisfaction. In 2006, the name of the museum was erased; now it is called the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas. To depersonalize the museum and to attribute it to the entire city also made its democratic point.

However, very quickly, the way things were going made people long for the “days of Sofía.” A year and a half after Sofía’s removal, in December 2002, the Miami-based Venezuelan marchand d’art and gallery owner Genaro Ambrosino was contacted about a sensational Matisse painting up for sale. It was difficult to imagine that a Venezuelan gallery owner did not have a pretty clear idea it was one of the masterpieces of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas. He immediately knew and decided to write some warning emails. When the Venezuelan cultural media received the news, they pointed to what Ambrosino had feared: the painting in the museum was a forgery that somehow had been exchanged for the original. Even before, in February 2001, Wanda de Guebriant, curator of the Matisse Archives, had reached the same conclusion when she was contacted in France by a possible buyer who asked her to examine the painting. The sellers had presented other forgeries: some documents of purchase, signed by Sofía Imber. De Guebriant didn’t believe anything and decided to call Sofía directly. The superficial part of the plot had been discovered, although there was a lot to figure out (see Marielena Balbi’s El rapto de la odalisca, edited in Caracas, 2009).

Everything indicates that Odalisque was removed between 1997, when it was exhibited in Spain, and 2001. Many think that the robbers took advantage of the trip to Spain. But the media talk about an audit ordered by the museum in 2001 that, according to its new director, Rita Salvestrini, discovered 14 artworks missing: Relaciones amarillo y plata (1964), Dos grandes barras (1971) y Escritura (1980), by Jesús Soto; Sketchbook 1980-A y Sketchbook 1980-B (sin fecha), by Henry Moore; Broom (1975), by Jasper Johns; Señas de identidad 1 y Señas de identidad 2 (1996), by Guido Anderloni; Untitled (no date), by Luis Barba; Untitled (1997), by Fernando Canovas; Untitled (1998), by Lucho Farías; Untitled (1998), by Antonio Murado; a series of drawings “Sin novedad en el frente Occidental” (1929), by Eugene Biel Bienne; and Tiempo y memoria (1995-1999), de Antonio Moya.

Salvestrini cautioned that some of the works could have been mislaid in the storage area or might be found in other branches of the museum. But 20 years later, there is no more information. If these works have been definitely lost, it’s just the tip of the iceberg and would indicate that the deterioration around the museum, and in the country at large, had managed to affect the museum since the 90’s more than we thought. Of course, what happened after 2001, as in all the institutions which left the control of the “fourth republic” that year, is an extreme case of the revolutionary “creative destruction” (more destructive than revolutionary). The last years of Sofía Imber were a bittersweet combination: the part of society that had detested her ceased to do so while those who loved her felt revindicated, transforming her into a civic heroine. But with all this came an exhausting decline of her physical capacity that did not impede her delight in life; and above all, her greatest sorrow, the long agony of her museum. “What is a museum without people, but a cadaver?” she asked in 2015, not long before she died.

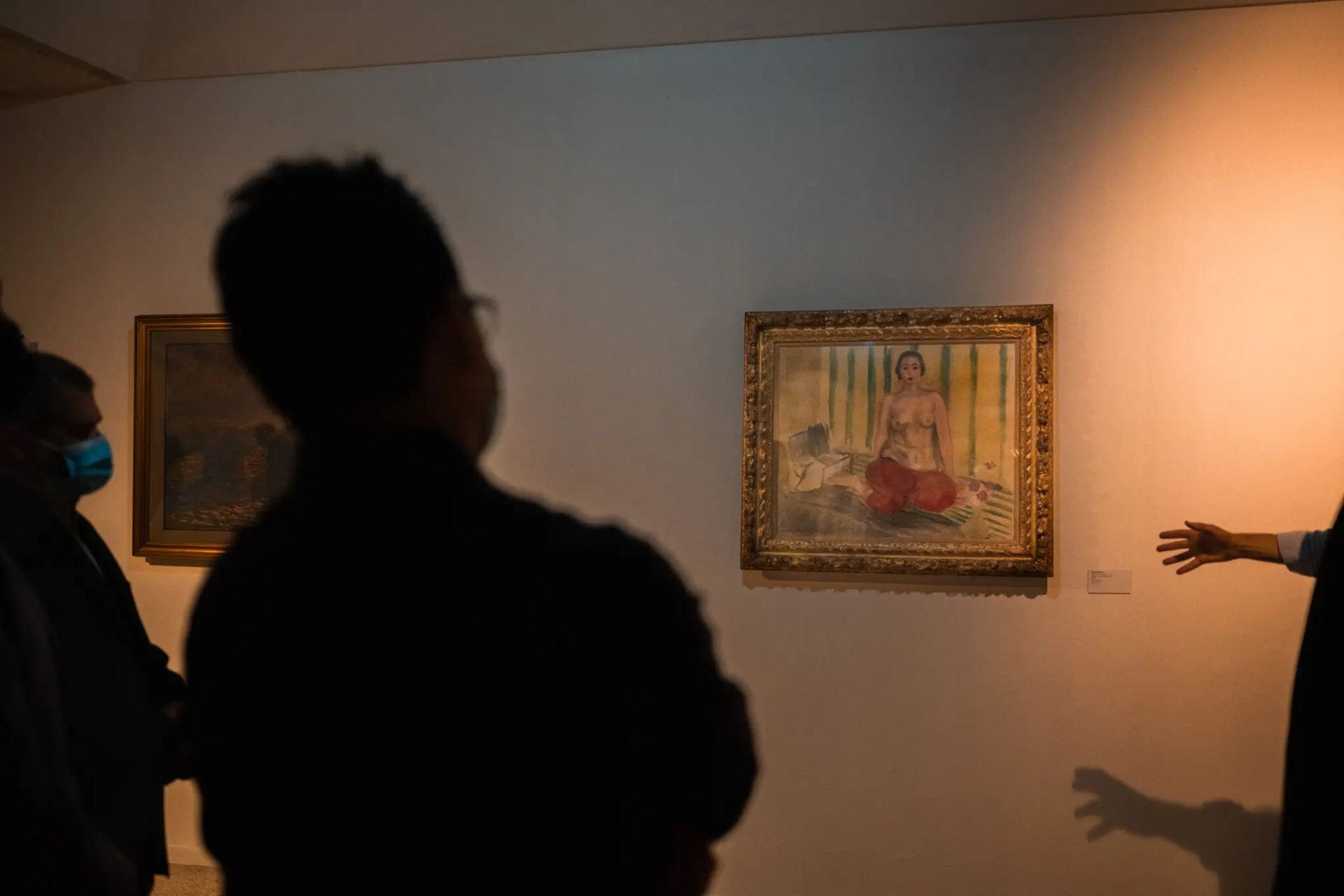

The Odalisque in Red Pants by Henri Matisse on display. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

The Moral of the Corpse

The cadaver had been very resistant to dying and could continue to walk around like a zombie–or perhaps like a golem, a clay creature brought magically to life that Sofía might have heard about in Jewish family stories—until the end of 2021. Going to the museum was painful, with its empty exhibition halls that were quite often closed. Without air-conditioning, subjecting the works of art to the humidity of the tropics. Almost without workers (although some stayed on out of love and stubbornness). With the fear that what had happened to Odalisque had been repeated with many other artworks. Finally, it just couldn’t survive, and the museum closed. Then the fear was that it would never reopen, although the Culture Ministry insisted that the closure had to do with major repairs. Against the worst presentiments, it kept its word and the museum reopened in February 2022.

If up until now, the history of the museum has been a metaphor for Venezuelan life since the 1950s, what can we say about its reopening? It’s difficult to know, but perhaps there are some indications. First, the scandal generated by the Odalisque and a true national crusade that in some way brought together the government of Nicolás Maduro and the opposition to recover the painting put the museum and how much it is appreciated in the spotlight. After the painting was finally returned in 2014, attention diminished, but some media reports about the state of the installations such as the much read and widely distributed articles by the journalist Sergio Monsalve, described a sufficiently bleak panorama that made the Culture Ministry respond. If something spurred the renovations and reopening, it was journalistic pressure.

As with so many other institutions with which Venezuela wanted to skip ahead to a dreamed-of year 2000 that never arrived, the museum never managed to change the destiny of the country, not even of Central Park, at least not in the form imagined. But it did sow something. All the controversy around Odalisque, the polemics about the museum’s closure and its reopening, its capacity for survival, although in a diminished form, suggests that the goal of the museum as a dynamic renovating force was not lost, not completely. Perhaps it’s a matter of waiting a little longer and the year 2000 will finally arrive, although delayed many years. It would be promising since, perhaps like nothing else, the museum is a metaphor for the country. In its high and low points, its moments of bonanza and scarcity and in its death and resurrection.

La Odalisca con Pantalón Rojo

Un Museo como Metáfora Nacional

Por Tómas Straka

La locación, los personajes y lo que está por suceder son propios de una novela negra: en una habitación del lujoso Hotel Loews de Miami, Pedro Antonio Marcuello Guzmán y María Martha Elisa Ornelas Lazo, esperan a los que creen los potenciales compradores de algo muy grande: nada menos que una de las odaliscas pintadas por pintor francés Henri Matisse, valorada en tres millones de dólares. Llevaban tiempo ofreciéndola de manera más o menos discreta, pero no habían hallado personas lo suficientemente ricas y, al mismo tiempo, confiadas o carentes de escrúpulos, como para aceptar una negociación como la que proponían. Encontrarse como amantes subrepticios en la habitación de un hotel auguraba cualquier cosa, menos una negociación normal. Llegaron los compradores. A partir de ahí no sabemos bien qué pasó en los minutos siguientes, pero debieron ser trepidantes. Seguramente pidieron ver la Odalisca con pantalón rojo, la estudiaron para cerciorarse de que se trataba de una obra original y, tal vez con un gesto propio de Hollywood, mostrar sus credenciales del FBI, revelarse como agentes encubiertos y arrestar a los dos vendedores.

Aquello fue el clímax de una historia en la que hubo muchos otros momentos cinematográficos. Encargar una falsificación de la Odalisca con pantalón rojo lo suficientemente buena como para que los curadores del Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Caracas no descubrieran de inmediato el robo; hallar el momento justo para sustraer el lienzo verdadero, colocar en su sitio a la falsificación, sacar de Venezuela a la obra e introducirla de algún modo en el mercado europeo, debió llevar meses de planificación e implicar a una amplia red de cómplices. Aunque ya hay al menos un largo reportaje sobre el hecho, tarde o temprano algún novelista o guionista sabrá darle buen uso a una trama tan rica.

El incidente sirve de eje para retratar no sólo el destino de los museos venezolanos durante el último medio siglo, sino en general lo que pasó con un país que a inicios de la década de 1970 pudo tener un museo inimaginable en América Latina, y que 40 años después, ve como una de sus obras emblemáticas es robada en medio de un declive que, en su punto más bajo, llevó prácticamente al cierre técnico del museo. Lo que pasó con la Odalisca y con el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo es una metáfora de la Venezuela que se creyó muy cerca de un futuro de desarrollo y prosperidad, que la imaginación ubicaba hacia el año 2000, y después, cuando por fin llegó el siglo XXI, sintió que ese futuro había quedado atrás, o había pasado de largo. Vamos a hacer un recorrido por ese periplo a través del museo y de su promotora principal, Sofía Imber (1924-2017).

Sofía Imber, Romanian-born Venezuelan journalist and the founder of the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas. Photo courtesy of Macsi.org.

El futuro que no fue

En 1973 estalla la crisis energética, los precios del petróleo inician una espiral ascendente que en cosa de ocho años los multiplicará por tres. En pocas partes han tenido un alcance y una permanencia como Venezuela. El país que por varias décadas había sido el primer exportador y el segundo productor mundial de petróleo, vio en el horizonte un boom de petrodólares mayor a los que ya había experimentado en la década de 1920 y con la crisis del Canal de Suez en 1956, incluso mayor al de los sueños de los venezolanos más optimistas. Era tanto el dinero que se atisbaba como un tornado en el horizonte, que la sensación fue de “ahora o nunca”. Carlos Andrés Pérez, candidato socialdemócrata que ese año arrasó en las elecciones presidenciales, le puso nombre al proyecto: la Gran Venezuela, desarrollada, dueña de sus recursos (las industrias del petróleo y el hierro estaban en manos extranjeras, sobre todo norteamericanas, por lo que se propuso nacionalizarlas) y próspera. Según sus planes, se llegaría a esta meta en el 2000.

Además de los petrodólares, había otras razones para el optimismo: Venezuela llevaba quince años de democracia, cuatro elecciones presidenciales libres consecutivas, cosa nunca antes vista en su historia; la última gran guerra civil había terminado setenta años atrás, en 1903; pese al esfuerzo hecho por todo el bloque comunista apoyando a la guerrilla venezolana, y a todas sus acciones bélicas y terroristas que llevó a cabo, ésta fue derrotada en seis años y no logró alterar la marcha del país. En medio del panorama latinoamericano, Venezuela era un ejemplo de estabilidad, libertad y políticas progresistas. Nadie negaba la persistencia de un montón de problemas, pero de cara a la región y a lo que el país había sido antes de la década de 1930, cualquier balance resultaba favorable. No en vano los venezolanos mostraban muy poca nostalgia por el pasado.

Por ejemplo, si algo caracterizó a aquellos años fue el cambio acelerado y a veces hasta violento del paisaje urbano. En todas las localidades en que fue posible, el Estado y los inversores privados echaron abajo la arquitectura colonial, cuya persistencia era vista como un signo de atraso. Hoy lo veríamos distinto, pero de 1940 hasta, al menos, mediados de los ochentas, se decidió lo mismo que ya habían decidido muchas ciudades europeas en el siglo XIX: demoler el pasado histórico para construir encima algo nuevo, en un proceso que algunos han comparado con el palimpsesto, esas piezas de pergamino a las que en la Edad Media se les borraba lo escrito para volver a escribir sobre ellas cosas nuevas. Caracas se convirtió así en un gran laboratorio de la modernidad urbanística y arquitectónica, pero el resto de las ciudades, cada una a su escala, hizo cuanto pudo al respecto. Si algo podía acercar el futuro, como quien estira tanto como puede su brazo y toma algo para llevar algo hacia sí, era la arquitectura, que habría de ponernos un escenario del 2000 (o de lo que se creyó iba a ser el 2000).

El complejo urbanístico de Parque Central es el epítome de aquel sueño. Como escribió, extasiado, José Balza en un relato de 1982, en él, en efecto, “todo pertenece al 2000”. Es decir, aquel 2000 soñado de 1982. Aunque ya se habían ensayado cosas similares, nunca algo de esa escala. Se trataba de demoler toda una urbanización de la década de 1930 (en aquella Caracas, cuarenta años ya hacían vieja a una urbanización) y sobre ella levantar un conjunto de rascacielos para la creciente clase media profesional, con todos los servicios para hacer como una especie de ultramoderna ciudad dentro de la ciudad. Se diseñaron también dos torres de oficinas, destinadas a ser las más altas de Sudamérica. El proyecto comenzó a construirse en 1970, antes del boom de los precios petroleros. De hecho, en un momento en el barril estaba a la baja. Si en esas circunstancias las cuentas daban para un proyecto así, es fácil imaginarse cómo se pusieron las cosas cuando los ingresos de un año a otro se multiplicaron por tres.

Dentro de Parque Central había de todo, o casi todo. Cine, supermercados, infinidad de locales comerciales, restaurantes, salas de convenciones. Sólo faltaba un museo de arte moderno, o al menos eso pensaron algunas figuras del mundo cultural caraqueño. Desde 1917 la ciudad tenía un Museo de Bellas Artes, que entonces, la verdad, estaba en franca expansión y modernización. Pero su nombre indicaba claramente lo que se hallaba en sus salas: sobre todo los grandes maestros de las beaux arts decimonónicas. La nueva ciudad literalmente que se estaba erigiendo sobre los escombros de la vieja requería algo más acorde con los tiempos. Así, en 1971 los planificadores de Parque Central piensan en un Museo de Arte Moderno, al que pronto se le cambia el nombre por Arte Contemporáneo, acaso con un espíritu epocal similar al de beaux arts: la contemporaneidad, como un nuevo período histórico que arrancaba en la década de 1960, había irrumpido en el pensamiento de Occidente. La intelectualidad estaba leyendo al historiador inglés Geoffrey Barraclough, quien declaró que con la llegada del hombre a la luna y los recientes cambios sociales estaba comenzando una nueva era histórica, y se sentían muy seguros (peligrosamente seguros) y orgullosos (también peligrosamente orgullosos) de arrancar un nuevo tiempo. Esta nueva era habría de vibrar en sus formas artísticas dentro de Parque Central, el corazón de la nueva ciudad, de la nueva Venezuela. En 1973 se establece una nueva asignatura en el bachillerato: la Historia Contemporánea de Venezuela. Y se crea, también, la Fundación Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, a cuya cabeza es nombrada la periodista Sofía Ímber. Si alguien podía llevarnos a ese año 2000 habría de ser ella.

Sculptures decorating the gardens that lead to the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

Carlos y Sofía

En el mundo intelectual, Carlos Rangel y Sofía Imber eran la pareja del momento. Amados y odiados con igual intensidad. Su programa de entrevistas matutino, que empezó a transmitirse en 1969, en su momento cambió a la televisión venezolana. Por más de 30 años ningún político o artista podía considerarse lo suficientemente consagrado, si no era auscultado por ellos. Ambos eran ya muy famosos en el mundo del periodismo, cuando sus amores fueron motivo de un abundante cotilleo. Los dos dejaron a sus respectivas parejas (que en el caso de Sofía era nada menos que el famoso escritor Guillermo Meneses), para vivir juntos. Sofía, cuyas crónicas irreverentes (por años tuvo una muy leída columna en El Nacional titulada “Yo, la intransigente”), ya daban de qué hablar, subió un par de decibeles las comidillas a su alrededor.

Pero la sociedad caraqueña muy rápido se acostumbró a ver a Carlos y a Sofía juntos, y se olvidó del chisme. Quienes no la perdonaron tan fácil fueron los intelectuales de izquierda, que entonces eran una abrumadora mayoría. Carlos y Sofía tenían a sus ojos un pecado mucho mayor al que cualquier beato pudo haber visto en sus amores: no sólo no eran comunistas, sino que eran las dos voces más claras y prominentes del anticomunismo en el mundo intelectual. Comoquiera que el país básicamente se había opuesto a la guerrilla y tenía entre sus ídolos a dos de sus más severos enemigos, Rómulo Betancourt y Carlos Andrés Pérez, eso no era un problema para el venezolano común. Pero en el mundo de las artes, la literatura, las universidades, la situación era diametralmente opuesta. En 1976 Carlos Rangel publicó Del Buen Salvaje al Buen Revolucionario, con un prólogo del filósofo francés muy reconocido Jean-François Revel y que de inmediato se convirtió en un best seller latinoamericano. El libro ha pasado a ser una especie de anti-[Eduardo] Galeano, señalando que los problemas de la región son, básicamente, culpa de los mismos latinoamericanos, no—como decía Galeano—de los imperialistas yanquís.

Para colmo, Sofía era una rusa blanca. Aunque llegó a Venezuela con sus padres cuando tenía seis años y siempre se sintió raigalmente venezolana, en sus primeros años se le vio como rusa, la “rusita”. En realidad no era rusa, sino de Moldavia, pero como país había sido independiente sólo u breve tiempo antes de su nacimiento, y antes fue parte del Imperio Ruso, después de Rumania y finalmente volvió a la Unión Sovietica, lo de rusa no estaba tan desencaminado: de haberse quedado en su tierra, habría sido ciudadana soviética la mayor parte de su vida. Además, básicamente ningún venezolano sabía de la existencia de Moldavia. Huyendo de las tormentas políticas y de los pogromos (los Imber eran judíos) su padres embarcaron hacia la lejana y desconocida Venezuela. Como a tantos otros inmigrantes de Europa central y oriental, les fue muy bien, tanto que sus hijas harían historia. La mayor, Lya Imber tuvo el mérito de ser la primera mujer en graduarse de médico en Venezuela. Sofía prefirió el periodismo.

Su biografía desde aquellos inicios reporteriles en los cuarenta hasta la fundación del museo es la encarnación de la modernidad en Occidente. La “rusita” a la que al principio sólo se le dejaban crónicas sociales, espacio propio para una señorita, sobre todo una refinada señorita europea, se volvió con el tiempo en una de las más importantes voces del periodismo cultural y político del país. Toda la modernización que había practicado con su propia vida, halló en su descubrimiento del arte moderno y la idea del museo un cauce institucional y trascendente.

A sculpture by Alexander Calder hanging in the vaults of the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

El museo de Caracas nace en París

La asombrosa colección del Museo de Arte Contemporáneo no puede desligarse de su antecedente inmediato: la Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, construida entre 1942 y 1954 (aunque muchas de sus partes se terminaron después). Diseñada por Carlos Raúl Villanueva es, con Brasilia, probablemente el referente de arquitectura moderna del siglo XX más importante de América Latina. La UNESCO la declaró Patrimonio de la Humanidad.

En el diseño y construcción de la Ciudad Universitaria confluyeron varias cosas afortunadas: los presupuestos cada vez más abultados del Estado, la convicción de todos los gobiernos que se sucedieron en aquella época de saltar al futuro, y de que eso habría de verse, antes que nada, en la principal universidad del país; y, por último pero no menos importante, el enorme talento de Villanueva, su conocimiento profundo de las vanguardias de principios de siglo, así como su amistad con muchos de sus principales representantes. El resultado fue la “integración de las artes” que logró Villanueva con obras de Jean Arp, Férnand Léger y Alexander Calder, entre muchos otros. Es posible imaginarlo a principios de los años 50s como el emisario de un lejano y riquísimo país tropical, como una especie de emirato actual, con un presupuesto al parecer ilimitado para encargar obras. Además, no era el único, constructores venezolanos contrataban arquitectos, ingenieros y artistas para sus proyectos en cantidades que no debieron pasar desapercibidas en el medio. Los venezolanos debieron ser bastante populares entonces. Pues bien, a ese París llega la “rusita” Sofía Imber con su esposo, el ya laureado escritor Meneses. Las circunstancias no dejan de ser polémicas: a Meneses lo había nombrado diplomático la dictadura militar que en 1948 dio al traste con el ensayo democrático iniciado tres años antes. Y no un cargo cualquiera: nada menos que Primer Secretario de la embajada.

Pero Meneses es tan irreverente como su joven esposa, ya había causado varios escándalos con sus cuentos en los treintas y pronto, con La Mano junto al muro, no sólo recibiría la arremetida de muchos, incluyendo la Iglesia, sino que marcaría un antes y un después en la literatura venezolana. Se trata, pues, de una pareja desenfadada, moderna, culta, en un París al que aún le quedaba mucho de capital mundial de las artes. Allí entran en contacto con Villanueva, que iba y venía desde Venezuela con frecuencia. Una Sofía curiosa y con bastante tiempo en París, a través de Villanueva conoció a Jean Arp y Henri Laurens. Hizo amistad con Picasso. Pronto entró a su corro Víctor Vasarely, cuya relación ha dado bastante material para el chismorreo (Sofía insistió en que sólo fueron amigos, que si bien se permitió algunos amantes, en este caso no fue así).

Chismes aparte, el hecho es que cuando la pareja retorna a Venezuela, ya Sofía venía como una erudita en arte moderno y una red de relaciones que, en pocos años, sería enormemente útil para el país. Según contó en una entrevista a su biógrafo, Diego Arroyo Gil, fue ella la que, al ver el desarrollo de Parque Central, le propuso al presidente del Centro Simón Bolívar (la compañía constructora del Estado que llevaba el proyecto) la creación del museo. También asegura que el paso de “moderno” a “contemporáneo” se debió a ella. Ambas cosas seguramente pueden ser matizadas, pero no parece haber duda en que tuvo participación importante en las dos decisiones. De un modo u otro, cuando en 1973 queda establecida la Fundación y escogidos los espacios en Parque Central (espacios que inicialmente no estaban pensados para un museo y que ella poco a poco arrebató a otros proyectos), llegó el momento de buscar las obras. Se le dio un presupuesto limitado, seguramente muy inferior a los manejados por Villanueva veinte años atrás, aunque con todo aún imposible para casi cualquier otro país latinoamericano en aquellos años: US$60.000. Con eso partió a Europa a buscar amigos, retomar contactos, encontrar otros nuevos y comprar las mejores obras posibles.

Al poco tiempo empezó a llegar a Caracas una colección que dejó a todos boquiabiertos: Duchamp, Kandinsky, Klee, Chagall, Gris, Picasso, mucho Picasso. En aquellos paquetes y obras envueltas, parecía, como nunca, que definitivamente el 2000 comenzaba a hacerse realidad.

A sculpture by James Mathison in the vaults. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

El museo de Sofía

El museo—el “museo de Sofía”, como lo llamaban sus amigos—se convirtió en una referencia en América Latina y en un orgullo para Venezuela. Los caraqueños y quienes visitaban la ciudad, podían apreciar una amplia colección de Picasso, Léger, Mondrian, Braque, Miró, Kandisnky, Warhol, entre muchos otros, poco común en el Tercer Mundo. El respeto y la capacidad de negociación de Sofía permitieron presupuestos para adquirir obras incluso cuando la situación económica comenzó a ser adversa. Sus contactos la ayudaron a conseguir donaciones, ya que no todo era comprado. La hoy famosa Odalisca con pantalón rojo fue comprada en 1981 en la Galería Marlborough de Nueva York, por US$480.000. Actuó como siempre: fue a la galería a ver qué había de nuevo, vio el cuadro, algo caro para su presupuesto, pero reunió de un modo u otro el dinero, y lo compró. Con ese empeño estructuró un equipo de trabajo de primera calidad, creó talleres, una estupenda biblioteca de arte, una tienda, un restaurant e hizo crecer el museo tanto como Parque Central lo permitió, hasta llegar a los 20.000 metros cuadrados. En 1990 el museo comenzó a llamarse Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Sofía Ímber (MACSI), homenaje en vida que no dejó de causar polémicas.

Pero cada vez más era una especie de burbuja en medio de un Parque Central, en general en medio de un país que había tomado otro camino. Un país que se estaba empobreciendo, ensuciando, desvencijando, marchitando A medida que se acercaba al 2000 Parque Central demostraba, en cada esquina, en cada pasillo, cómo las promesas de los setentas no se pudieron cumplir. El otrora conjunto al que se mudó mucho del mundo artístico caraqueño, fue envejeciendo y deteriorándose como la clase media que lo habitaba y como el Estado que administraba todo el conjunto urbanístico. Fuentes sin agua, pasillos oscuros, ascensores que no funcionaban, escaleras mecánicas detenidas, pisos más bien sucios, boutiques y restaurantes que demostraban haber tenido tiempos mejores, cada vez más historias de robos, contrastaban cada vez más con un museo que insistía en mantenerse reluciente. El siglo XXI encontró a Venezuela con un 70% de pobres y algo menos de un 10% de ricos, después de haber tenido una amplia capa media, de alrededor del 60% en los años setenta.

Es decir, ese mundo que ajado del resto de Parque Central, esas personas que se habían mudado a un sitio en el que “todo pertenece al 2000”, y ahora debían hacer colas para tomar los pocos ascensores en funcionamiento, los dueños de esas boutiques que luchaban por no cerrar, los empleados de los ministerios era imposible que no viera de reojo al museo con sus obras de Picasso, Warhol, Matisse… No hablamos en sí de Parque Central, sino de toda la sociedad que creyó que en el 2000 iba a ser moderna y próspera, y se encontró pobre y escacharrada. Fue la sociedad que votó mayoritariamente por Hugo Chávez en la seguidilla de elecciones que les dieron todo el poder entre 1999 y 2006. Un museo tan firmemente enraizado en las líneas fundamentales de desarrollo del país, tan orgánica, existencialmente venezolano, no podía sustraerse por demasiado tiempo de todo esto. Parodiando un poco a Balza, puede decirse que en el 2000 en Parque Central todo parecía de 1970.

Visitors looking at a Picasso painting shortly after the partial reopening of the museum. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

Después del futuro

Para 2001 ya Chávez había dado pasos muy firmes en la demolición del régimen anterior. La anticomunista Sofía difícilmente podía sobrevivir al cambio. La emblemática modernizadora de la “cuarta república”, como llamó al régimen anterior para diferenciarlo del suyo (“quinta república”), era uno de los tantos símbolos que había que echar abajo. Además, hay que recordar que siempre fue amada y odiada con intensidad. Muchos de los que la odiaban, naturalmente, eran aquellos artistas y académicos izquierdistas que ahora se nucleaban en torno a Chávez. Algunas de sus críticas tenían sentido, naturalmente: treinta años a la cabeza de una institución pública pueden traducirse en una especie de feudo; el nombre del museo denotaba personalismo, que muchos acusaban en su gerencia: eso de “el museo de Sofía” podía no ser necesariamente una virtud. Aunque el personalismo y el deseo de perpetuidad en el poder pronto se hicieron propios del chavismo, eso en 2001 no estaba claro para muchos, o de estarlo, de todos modos no obstaba para encontrar, por fin, algo con que deshacerse de Sofía.

Ella estaba perfectamente consciente de que no podía tener un lugar en el Estado chavista. De hecho, estaba convencida de que había llegado el momento de renunciar, pero Chávez, como solía hacer, se adelantó a los hechos. En su programa dominical del 21 de enero de 2001 proclamó: “¡qué difícil es este mundo de la cultura! ¡Cómo se ha manejado!”, disparando de inmediato: “la cultura se vino elitizando, manejada por élites, como dijo [el pintor venezolano] Manuel Espinoza: un principado…. Príncipes, reyes, herederos, familias, se adueñaron de instituciones, de instalaciones que les cuestan miles de millones de bolívares al Estado”. Acto seguido, la despidió. Su destitución fue aplaudida por muchos, con sonrisa de satisfacción. En 2006 se eliminó su nombre del museo, que ahora se llama Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Caracas. Despersonalizar al museo y adscribirlo a toda la ciudad, tienen también su punto democrático.

Sin embargo, muy rápidamente las cosas hicieron suspirar por los días en que fue “de Sofía”. Un año y medio después de la destitución, en diciembre de 2002, al marchand d’art y galerista venezolano Genaro Ambrosino, radicado en Miami, fue contactado acerca de un sensacional cuadro de Matisse que estaba a la venta. Era difícil que un galerista venezolano no tuviera una idea bastante clara de una de las masterpieces del Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Caracas. Inmediatamente supo de qué se trataba y decidió escribir varios emails para dar la señal de alerta. Cuando la noticia llegó a los medios culturales venezolanos, apuntaló lo que se temía: que el cuadro que estaba en el museo era una falsificación, que de alguna manera había sido cambiado por el original. Ya antes, en febrero del 2001, Wanda de Guebriant, curadora de los Archivos Matisse, había llegado a la misma conclusión cuando fue contactada en Francia por un posible comprador que le pidió que examinara el cuadro. Lo reconoció de inmediato y preguntó cómo había llegado hasta allá. Le presentaron otras falsificaciones: unos documentos de compra, firmados por Sofía Imber. De Guebriant no creyó nada, y decidió llamar directamente a Sofía. La parte superficial de la trama se había puesto al descubierto, aunque aún queda mucho más por resolver (vea El rapto de la odalisca, de Marielena Balbi, editado en Caracas en 2009).

Todo apunta a que la Odalisca había sustraída en algún momento entre 1997, cuando fue expuesta en España, y 2001. Muchos piensan en que el viaje a España fue aprovechado para el hurto. Pero los medios hablan de una auditoría ordenada por el museo en el mismo 2001, que, según señaló su nueva directora, Rita Salvestrini, arrojó catorce obras desaparecidas: Relaciones amarillo y plata (1964), Dos grandes barras (1971) y Escritura (1980), de Jesús Soto; Sketchbook 1980-A y Sketchbook 1980-B (sin fecha), de Henry Moore; Broom (1975), de Jasper Johns; Señas de identidad 1 y Señas de identidad 2 (1996), de Guido Anderloni; Sin título (sin fecha), de Luis Barba; Sin título (1997), de Fernando Canovas; Sin título (1998), de Lucho Farías; Sin título (1998), de Antonio Murado; la serie de dibujos titulados “Sin novedad en el frente Occidental” (1929), de Eugene Biel Bienne; y Tiempo y memoria (1995-1999), de Antonio Moya.

Salvestrini advirtió que probablemente algunas de las obras estaban mal ubicadas en el depósito, o se encontraban en otras dependencias. A veinte años, en los medios no se halla más información. Pero si se perdieron definitivamente, tal vez estemos ante la punta del iceberg, y haría pensar que el declive que ya se acusaba en los alrededores del museo, y en general en el país, desde los años noventa había logrado salpicarlo más de lo que pensamos. Por supuesto, lo ocurrido después de 2001, como en todas las instituciones en las que en ese año terminan de salir de las manos de la “cuarta república”, es un caso extremo “destrucción creadora” revolucionaria (en realidad más lo primero que lo segundo). Los últimos años de Sofía Imber fueron la combinación agridulce de una mujer a la que, por fin, dejó de odiar la parte de la sociedad que hasta la víspera la detestó, mientras los que siempre la amaron la vieron reivindicada, convirtiéndola en una heroína cívica. Pero todo ello con una agobiante disminución de sus capacidades físicas, que sin embargo no mermó sus ganas de vivir; y sobre todo, su mayor dolor: con la agonía larga de su museo. “¿Qué es un museo sin gente sino un cadáver?”, dijo en 2015, poco antes de ella misma morir.

The Odalisque in Red Pants by Henri Matisse on display. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

La moraleja del cadáver

El cadáver ha sido muy resistente y pudo seguir andando como un zombi –o acaso como un Gólem, figura que a lo mejor oyó Sofía en sus cuentos familiares—hasta finales de 2021. Ir al museo era doloroso, con sus salas vacías y, cada vez más, cerradas. Sin aire acondicionado, sometiendo a las obras a la humedad del trópico. Casi sin empleados (aunque sí con algunos que tenaz y amorosamente se empeñaron en mantenerlo en pie). Con el temor de que lo de la Odalisca se haya repetido con muchas otras obras. Al final, no pudo más, y cerró. Entonces el temor era el de que no volviera a abrir más, por mucho que el Ministerio de Cultura insistió en que se trataba sólo de reparaciones mayores. Contra los peores barruntos, cumplió su palabra y en febrero de 2022 reabrió.

Si hasta el momento la historia del museo ha sido una metáfora de la vida venezolana desde mediados del siglo pasado, ¿qué puede decirnos esta reapertura? Es muy difícil saberlo, pero puede ser útil consignar algunos datos para cerrar. Primero, que el escándalo que generó lo de la Odalisca y la verdadera cruzada nacional, que de algún modo abarcó al gobierno de Nicolás Maduro y a sus opositores, por recuperarla, puso de relieve al museo y demostró cuánto se le apreciaba. Después de que el cuadro finalmente retornó en 2014, la atención bajó, pero algunos reportajes sobre el estado de las instalaciones, como el muy leído y difundido del periodista Sergio Monsalve, ofrecieron un panorama lo suficientemente malo como para que el Ministerio de Cultura se sintiera en la obligación de dar la cara. Si algo acicateó los trabajos y la reapertura, fue esta presión periodística.

Como pasó con tantas otras instituciones con las que Venezuela quiso saltar al 2000 soñado y jamás llegado, el museo no logró cambiar el destino del país, ni siquiera el de Parque Central, al menos no cómo y cuando se pensó. Pero algo sembró. Todo lo de la Odalisca, la polémica por su cierre, la reapertura, su capacidad para sobrevivir, aunque sea muy disminuido, indica que lo que se quiso hacer con él, como dínamo de energía renovadora, no se perdió, siquiera no por completo. Tal vez es cosa de esperar un poco más y el 2000 por fin llegue, aunque sea muchos años después. Sería hasta esperanzador, ya que, como ninguno, su historia demuestra hasta qué punto la historia de un museo es la metáfora de la de todo un país. En sus altas y en sus bajas, en sus momentos de bonanza y de inopia, en su muerte y en su resurrección.

Tomás Straka is a Venezuelan historian and essayist. Director of the Institute of Historical Research at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (Caracas), he is a columnist for several newspapers and websites. He is the author of several works, which include essays, textbooks and monographs.

Tomás Straka es historiador y ensayista venezolano. Director del Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas de la Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (Caracas), el es columnista de varios medios y portales. Es autor de diversos trabajos, que incluyen ensayos, manuales escolares y estudios monográficos.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.