The Erotics of Play

An Asexual Reading of the Poetic Work of José María Eguren

José María Eguren seems to have had no interest in sexual activity. A renowned professor of contemporary poetry told us when he introduced this prominent Peruvian poet of the twentieth century. Ten years have passed, but I still remember his musings and reformulations as he tried to convince us of what he had just stated.

From that day on, Eguren caused me an enormous feeling of resemblance and empathy. At that time, I did not share his hobbies, so the reason for such identification was a mystery to me. At least it was until a few years later when I discovered what it was to be asexual and identified as one. However, it never ceases to amaze me how such a simple statement could be controversial enough to require justification.

My professor compared Eguren to César Moro, another poet whose vigorous libido and busy sexual activity were widely present in his romantic poetry. He then turned to biographical evidence: Eguren never married, had no known romantic partners, and lived with his sisters and their children. In addition to being a genius poet, he was known for being a nature lover, fond of photography and oil and watercolor painting.

Self-portrait Oil painting. Cardboard canvas. Eguren, José María, comp. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden. Obra Plástica. Biblioteca Abraham Valdelomar, 2017.

The reason for his lack of sexual interest was not explicitly stated, but the underlying message was that Eguren had a pure and childlike soul. This apparent explanation only raised more questions for me: what is the link between purity, childhood and lack of sexual interest, is there a failure or lack in life or in poetry if one has no sexual interest, how does this relate to asexuality?

The Asexual Visibility and Education Network defines asexuality as the sexual orientation of those who possess little or no sexual attraction. It can also be understood as the lack of sexual desire. Like all dissident sexual orientations, asexuality also receives its share of ignorance, misunderstanding and discrimination. Usually asexual people are not validated, are pathologized or infantilized.

Most of the theoretical or cultural production on asexuality in Spanish-speaking countries comes from Spain, Mexico and Argentina. In Latin American countries it is particularly difficult to establish asexual communities, since, in addition to ignorance and discrimination, there are the stereotypes of Latin sexuality as exuberant. In the case of Peru, I found that the production of knowledge on the subject is practically non-existent and the asexual community is currently inactive.

Let’s go back to our poet in question. Eguren is considered by many scholars as one of the first representatives of Peruvian children’s literature. His work is full of fantasy worlds and characters. Hence his best known poetry books are called Symbolics and The Song of the Figures. In addition, his poetry was clearly influenced by French symbolism. It was not necessarily addressed to children but it did capture or draw on children’s imagination.

In his work, the children’s characters are usually female. The Egurenian woman is defined as an idealized being, similar to the donna angelicata or femme fragile. She may possess sensual characteristics, but not sexual ones. Hence, the poetic voice remains distant and contemplative. In the words of literary critic Jorge Basadre, “she is not the female and she is not the lady. The thrill of the flesh, of sex, never appears here” (Aproximaciones y Perspectivas, 1977) (translation by Estef Calderón).

Consequently, other critics such as the poet Xavier Abril conclude that Eguren was not a poet of passions because “he did not know how and could not express, through his poetry, the mature and overwhelming passion of vital resonances” (Eguren, El Obscuro: El Simbolismo En América, 1970) (translation by Estef Calderón). However, I know that no one can say that the poet’s “immature passion” is caused by a childish mentality or puerile motivations, for Eguren dealt with the bitterness of life and human misery with the same genius with which he treated feerical fantasies.

What, then, is going on with the poet’s passion? To answer this, I consider it necessary to make a clear distinction between sexuality and eroticism. These terms do not mean the same thing. From the Greek tradition, eros is one form of love, among many others, that is not limited to sexual passion.

Today, asexual critique takes this notion and raises a new way of understanding eroticism. Illinois State University professor Ela Przybylo, in her book Asexual Erotics: Intimate Readings of Compulsory Sexuality, posits that erotics are the various forms of intimacy that are not narrowed down to sex and sexuality. This proposal challenges the Freudian tradition that limits eros to “the sexual” and fixes it as the vital force and libidinal energy “behind all human progress, action, and ‘civilization’ itself” (August, 2019).

The term erotics comes from a lesbian feminist and anti-racist lineage. Przybylo draws on writer Audre Lorde’s essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power (1978)” to argue that deep intimacy “is not reliant only on sex and sexuality for meaning but that it finds satisfaction in a myriad of other activities and relationships to the self and to others” (August, 2019).

Erotics is an umbrella term that can include different forms of pleasure. Sex would be one of them, but not the only or most important one. Other equally valid forms would be the pleasure of bonding in non-sexual ways with others, being able to create joy for ourselves and for others, knowing ourselves, and engaging in activities that are mundane but exciting or meaningful to us, from writing poetry to being part of a fandom.

With this in mind, I claim that the Eugurenian poetic voice does sustain an erotic bond with the female figures present in the poems, but the pleasure it derives through them is not sexual. It finds pleasure in the activities of contemplation and play, for these generate introspection, joy, and the experience of engaging in mundane activities of enjoyment; it is a form of asexual erotic pleasure.

Let’s explain this further. I agree with many critics in identifying the girl as the most interesting and recurrent character in the poems. The poems whose main character is the girl are eminently fresh, candorous and fanciful. The universe in which she is immersed is a childish one in which everything that happens is part of the imagination, of play.

Dream Watercolor Eguren, José María, comp. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden. Acuarelas: Un Álbum de José María Eguren. Biblioteca Nacional Del Perú, 2021.

Poems that meet these characteristics are The Duke, A marionnette’s funeral march and The dummy, among others. In them the protagonist is a girl and the stories told are the games she plays. In a fragment of The duke, we read:

Today marries Duke Chestnut;

comes the cantor, comes the judge

and with the pennants in scarlet

a flowery cavalcade;

at a one, at a two, at a ten;

that gets married the Duke primrose

with the daughter of Spicy Clove.

(…)

but the Duke he doesn’t come;…

Paquita has eaten him.

In this poem, the girl named Paquita describes how she plays with her dessert. She imagines a medieval palace scene in which elements of her food take on the role of characters in her fantasy. The play is animistic and naturistic, as these are qualities characteristic of children’s fantasy.

In this way, I argue that the Egurenian girl lives in a perpetual state of playfulness and finds her greatest pleasure in play. I also observe that this activity generates in the poetic voice the same erotic pleasure, since it is conceived as a vital creative force. In Eguren’s own words:

The child awakens to curiosity, follows its colorful race, every detail is a surprise, an enchanted story, whose memory will lead him to imitation and creation. But the child is a creator in moments; every game, every inventiveness, every mischief is a living art. The child is a movement of art, an aesthetic dynamism. As aesthetics is the science of the heart, the heart of the child must be cultivated in the path of energy, freedom and nobility; in the field of beauty that refines the soul and exalts man. For the child it is necessary to live in beauty; because it gives him an optimistic concept of life, which constitutes a force (Obra poética. Motivos, 2005) (translation by Estef Calderón).

For Eguren, then, play is positioned as a form of asexual erotic pleasure that, like Freudian sexual pleasure, provides a vital force and libidinal energy. Through play, a dynamic, creative and aesthetic force is obtained which, if cultivated, provides the individual with energy, freedom and nobility.

Andrew Grossman, in his essay “‘Why Didn’t You Tell Me That I Love You?’ Asexuality, Polymorphous Perversity, and The Liberation of the Cinematix Clown”, suggests using the term polymorphous sexuality to understand other forms of pleasure that were canceled after growing up and “outgrowing” the oral, anal, and phallic stages of psychosexual development.

According to Grossman, “civilization must annihilate the freely roaming, unprejudiced perversities we enjoy as children to make way for an adulthood of linear goals and progress, even if that process obliges us to lose a more innocent, diverse, and playful hedonism” (Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives, 2016). Thus, in the process of children’s socialization, reproductive sexuality is determined as the correct one, unconventional sexualities are pathologized, and asexual pleasures are identified as childish.

Therefore, “mature” erotic pleasure is limited to reproductive sexual pleasure centered on genitality, while other forms of asexual erotics are qualified as immature. Hence, the egurenian infantile fantasy is considered as intrusive and sabotaging because it cancels the development of a sexual erotic. Thus, the hedonism achieved only through the girl’s play is considered a flaw in his poetic work.

However, I believe that claiming this implies a huge inconsistency, since our most pleasurable adult fantasies are, in fact, non-sexual. As Grossman himself warns, they correspond to the “realm of everyday “play”, daydreaming, and poetic flights of whimsy-all commonly regarded as “intrusions” into the narrow, industrious mandates of adulthood and masculinity” (Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives, 2016).

Within the asexual community, asexual men are usually the most invalidated, since the social pressure to perform hypersexuality to reaffirm their identity falls much more on them than on women. The lack of sexual interest or practice of sexual activities are qualities better accepted in women as they are associated with innocence and purity, qualities traditionally valued in the female gender performance.

Therefore, it does not seem strange to me that Eguren found in ladies, princesses and girls the ideal subject to explore more freely the asexual erotics. The adults in his work are usually men. They are portrayed in opposition to the girl and are described as dark, malicious and deadly figures, as they threaten to put an end to her asexual pleasure by imposing their own sexual pleasure.

The Spirit of the Night Watercolor Eguren, José María, comp. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden. Acuarelas: Un Álbum de José María Eguren. Biblioteca Nacional Del Perú, 2021.

In poems such as Nora or Blazon, the girl is or runs the risk of being harassed by men who want to satisfy their sexual desires with her. The scenario is described as a painful tragedy, as the imposition of male sexual pleasure consumes and suppresses the girl’s asexual vital force.

However, I find that not every interaction with a male subject ends in tragedy. The poem The girl of the lamplight blue is the most emblematic of Eguren’s work, as it reflects the poet’s leitmotif. Here the girl appears again as the protagonist, but it is she who approaches and offers to guide the male poetic voice. In a fragment we read:

With voice childish and melodious

in fresh aroma of birch shrub,

talks of a life miraculous

the girl of the lamplight blue.

With warm eyes of sweetness

and kisses of matutine love,

the beautiful creature offers me

a magic and celestial road.

Of incantation in a splurge,

rives elated, vaporous tulle;

and across the night she guides me

the girl of the lamplight blue.

Like the literary critic, I identify this male poetic voice with Eguren himself, since it is he who explores this marvelous, magical and celestial path in all his literary and plastic work. At the same time, I find that the girl is the body and the identity that allow such exploration, for she embodies the playful pleasure of asexual erotics.

Thinking about Eguren’s work leaves me with a tender nostalgia and some bitterness. In poetry, the fantasy of play makes its triumphant way. However, in reality, it is flanked. It has a place in childhood, but is questioned or rejected in adulthood as it is considered immature or damaged.

Sexuality is also a social construct and biopower device that can be used to invalidate, discriminate and pathologize individuals. I hope that talking about erotics will allow us to understand and explore different forms of sexual and asexual pleasure without labeling them as mature or immature, normal or deviant, superior or inferior. It makes no sense to feel shame or guilt for enjoying them. Immature passions simply do not exist.

La erótica del juego

Una lectura asexual de la obra poética de José María Eguren

Por Estef Calderón Villón

José María Eguren parece no haber tenido interés en la actividad sexual. Nos dijo un reconocido profesor de lírica contemporánea cuando introdujo a este destacado poeta peruano del siglo XX. Han pasado ya diez años, pero todavía recuerdo sus cavilaciones y reformulaciones al intentar convencernos de lo que acababa de afirmar.

Desde ese día, Eguren me causa un enorme sentimiento de semejanza y empatía. En aquel momento, no compartía sus hobbies, así que la razón de tal identificación fue un misterio para mí. Al menos lo fue hasta unos años después cuando descubrí lo que era ser asexual y me identifiqué como tal. Sin embargo, no deja de sorprenderme cómo una afirmación tan simple podía ser lo suficientemente polémica como para exigir una justificación.

Mi profesor comparó a Eguren con César Moro, otro poeta cuya vigorosa libido y ocupada actividad sexual sí se encontraban ampliamente presentes en su poesía amorosa. Luego recurrió a la evidencia biográfica: Eguren nunca se casó, no se le conocieron parejas sentimentales y vivió con sus hermanas y los hijos de estas. Además de genio poeta, fue conocido por ser amante de la naturaleza, aficionado a la fotografía y la pintura al óleo y acuarelas.

Autoretrato Óleo. Tela adherida sobre cartón. Eguren, José María, comp. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden. Obra Plástica. Biblioteca Abraham Valdelomar, 2017.

La razón de su falta de interés sexual no fue formulada explícitamente, pero el mensaje subyacente fue que Eguren tenía un alma pura e infantil. Esta aparente explicación solo me generó más preguntas: ¿Cuál es la relación entre la pureza, la infancia y la falta de interés sexual?, ¿existe una falla o carencia en la vida o en la poesía si no se tiene interés sexual?, ¿cómo se relaciona esto con la asexualidad?

The Asexual Visibility and Education Network define a la asexualidad como la orientación sexual de aquellos que poseen poca o ninguna atracción sexual. También puede ser entendida como la falta de deseo sexual. Como toda orientación sexual disidente, la asexualidad también recibe una porción de desconocimiento, incomprensión y discriminación. Usualmente no se valida, se patologiza o se infantiliza a las personas asexuales.

La mayoría de producción teórica o cultural sobre la asexualidad en habla hispana proviene de España, México y Argentina. En los países latinoamericanos es particularmente difícil establecer comunidades asexuales, puesto que, además del desconocimiento y la discriminación, están los estereotipos de la sexualidad latina como desbordante. En el caso de Perú, encontré que la producción de conocimiento sobre el tema es prácticamente inexistente y la comunidad asexual se encuentra actualmente inactiva.

Regresando a nuestro poeta en cuestión, Eguren es considerado por muchos académicos como uno de los primeros representantes de la literatura infantil peruana. Su obra está plagada de mundos y personajes fantasiosos. De ahí que sus poemarios más conocidos se llamen Simbólicas y Canción de las figuras. Al mismo tiempo su poesía estaba claramente influenciada por el simbolismo francés. No estaba necesariamente dirigida a niños pero sí capturaba o se nutría de la imaginación infantil.

En su obra, los personajes infantiles son usualmente femeninos. La mujer egureniana es definida como un ser idealizado, similar a la donna angelicata o femme fragile. Puede poseer características sensuales, pero no sexuales. De ahí que la voz poética se mantenga distante y en actitud contemplativa. En palabras del crítico literario, Jorge Basadre, “ella no es la hembra y no es la dama. El estremecimiento de la carne, del sexo, no aparecen nunca aquí” (Aproximaciones y Perspectivas, 1977).

En consecuencia, otros críticos como el poeta Xavier Abril concluyen que Eguren no fue un poeta de pasiones pues “no supo ni pudo expresar, a través de su poesía, la pasión madura, avasalladora de resonancias vitales” (Eguren, El Obscuro: El Simbolismo En América, 1970). Sin embargo, sé que nadie podrá decir que la “pasión inmadura” del poeta es causada por una mentalidad infantil o motivaciones pueriles, pues Eguren trató sobre la amargura de la vida y miseria humana con la misma genialidad con la que trató las fantasías feéricas.

¿Qué sudece entonces con la pasión del poeta? Para responder esto, considero necesario plantear una clara distinción entre sexualidad y erotismo. Estos términos no significan lo mismo. Desde la tradición griega, eros es una forma de amor, entre muchas otras, que no está limitada a la pasión sexual.

Actualmente, la crítica asexual toma esta noción y plantea una nueva forma de entender la erótica. La profesora de Illinois State University Ela Przybylo, en su libro Asexual Erotics: Intimate Readings of Compulsory Sexuality, plantea que las eróticas son las distintas formas de intimidad que no se reducen al sexo y a la sexualidad. Esta propuesta desafía la tradición freudiana que limita al eros a “lo sexual” y lo posiciona como la fuerza vital y energía libidinal “behind all human progress, action, and “civilization” itself” (agosto, 2019).

El término erotics proviene de un linaje feminista lésbico y antiracista. Przybylo se basa en el ensayo de la escritora Audre Lorde Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power (1978) para plantear que la intimidad profunda “is not reliant only on sex and sexuality for meaning but that finds satisfaction in a myriad of other activities and relationships to the self and to others” (agosto, 2019).

La erótica es un término paraguas que puede incluir diferentes formas de placer. El sexo sería una de ellas, pero no la única o la más importante. Otras formas igualmente válidas serían el placer de vincularnos de forma no sexual con otros, el ser capaz de generar y generarnos alegría, el conocernos a nosotros mismos y el realizar actividades mundanas pero emocionantes o significativas para nosotros, desde escribir poesía hasta pertenecer a un fandom.

Teniendo esto en cuenta, planteo que la voz poética egureniana sí sostiene un vínculo erótico con las figuras femeninas presentes en los poemas, pero el placer que obtiene a través de ellas no es sexual. Ella encuentra placer en las actividades de contemplación y juego, pues estas generan introspección, alegría y la experiencia de realizar actividades mundanas de disfrute; se trata de una forma de placer erótico asexual.

Expliquemos mejor esto. Coincido con muchos críticos en identificar a la niña como el personaje egureniano más interesante y recurrente. Los poemas que tienen por personaje protagónico a la niña son eminentemente frescos, candorosos y fantasiosos. El universo en el que está inmersa es uno infantil en el que todo lo que ocurre es parte de la imaginación, del juego.

Sueño Acuarela Eguren, José María, comp. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden. Acuarelas: Un Álbum de José María Eguren. Biblioteca Nacional Del Perú, 2021.

Poemas que cumplen con estas características son El duque, Marcha fúnebre de una marionnette y El pelele, entre otros. En ellos la protagonista es una niña y las historias contadas se tratan de juegos creados por ella. En un fragmento de El duque, se lee:

Hoy se casa el Duque Nuez;

viene el chantre, viene el juez

y con pendones escarlata

florida cabalgata;

a la una, a las dos, a las diez;

que se casa el Duque primor

con la hija de Clavo de Olor.

(…)

Pero el Duque no viene;

Se lo ha comido Paquita.

En este poema, la niña de nombre Paquita describe cómo juega con su postre. Ella imagina una escena palaciega medieval en la que elementos de su comida toman el rol de personajes en su fantasía. El juego es animista y naturista, ya que estas son cualidades propias de la fantasía infantil.

De esta forma, establezco que la niña egureniana vive en un perpetuo estado lúdico y encuentra su mayor placer en el juego. Observo también que esta actividad genera en la voz poética el mismo placer erótico, pues lo concibe como una fuerza vital creadora. En palabras del propio Eguren:

El niño despierta a la curiosidad, sigue su carrera de colores, cada detalle es una sorpresa, un cuento encantado, cuyo recuerdo lo llevará a la imitativa y creación. Pero el niño es creador en los momentos; cada juego, cada inventiva, cada travesura es un arte viviente. El niño es un movimiento de arte, un dinamismo estético. Como la estética es la ciencia de corazón, se debe cultivar el corazón del niño en ruta de energía, libertad y nobleza; en el campo de lo bello que afina el alma y enaltece al hombre. Para el niño es necesario vivir en belleza; porque le da un concepto optimista de la vida, que constituye una fuerza (Obra poética. Motivos, 2005).

Para Eguren, entonces, el juego se posiciona como una forma de placer erótico asexual que, al igual que el placer sexual freudiano, proporciona una fuerza vital y energía libidinal. A través del juego, se obtiene una fuerza dinámica, creativa y estética que, si se cultiva, brinda al individuo energía, libertad y nobleza.

Andrew Grossman, en su ensayo “‘Why Didn’t You Tell Me That I Love You?’: Asexuality, Polymorphous Perversity, and The Liberation of the Cinematix Clown”, plantea usar el término polymorphous sexuality para entender otras formas de placer que fueron canceladas luego de crecer y “superar” las etapas oral, anal y fálica del desarrollo psicosexual.

De acuerdo a Grossman, “civilization must annihilate the freely roaming, unprejudiced perversities we enjoy as children to make way for an adulthood of linear goals and progress, even if that process obliges us to lose a more innocent, diverse, and playful hedonism” (Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives, 2016). Por ello, en el proceso de socialización de los niños se determina a la sexualidad reproductiva como la correcta, se patologiza sexualidades no convencionales y se identifica placeres asexuales como infantiles.

De esta forma, el placer erótico “maduro” queda limitado al placer sexual reproductivo centrado en la genitalidad, mientras que otras formas de erotismo asexual son calificadas de inmaduras. Por ello, la fantasía infantil egureniana es considerada como intrusiva y saboteadora pues cancela el desarrollo de una erótica sexual. Es así como el hedonismo logrado únicamente a través del juego de la niña es considerado una falencia en su obra poética.

Sin embargo, considero que afirmar esto implica una enorme inconsistencia, puesto que nuestras fantasías adultas más placenteras son, en realidad, no sexuales. Como Grossman mismo lo advierte, ellas corresponden al “realm of everyday “play”, daydreaming, and poetic flights of whimsy –all commonly regarded as “intrusions” into the narrow, industrious mandates of adulthood and masculinity” (Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives, 2016).

Dentro de la comunidad asexual, los hombres asexuales son usualmente los más invalidados, puesto que la presión social de performar una hipersexualidad para reafirmar su identidad recae mucho más sobre ellos que sobre las mujeres. La falta de interés sexual o práctica de actividades sexuales son cualidades mejor aceptadas en mujeres al estar asociadas con la inocencia y pureza, cualidades tradicionalmente valoradas en la performance del género femenino.

Por eso no me parece extraño que Eguren encontrara en las damas, princesas y niñas el sujeto ideal para explorar más libremente las eróticas asexuales. Los adultos en su obra suelen ser hombres. Estos son construidos en oposición al personaje de la niña y son descritos como figuras oscuras, maliciosas y mortíferas, pues amenazan con darle fin a su placer asexual imponiendo su propio placer sexual.

El Espíritu de la Noche Acuarela Eguren, José María, comp. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden. Acuarelas: Un Álbum de José María Eguren. Biblioteca Nacional Del Perú, 2021.

En poemas como Nora o Blasón, la niña es o corre el riesgo de ser acosada por hombres que quieren satisfacer sus deseos sexuales con ella. El escenario es descrito como una penosa tragedia, pues la imposición del placer sexual masculino consume y anula la fuerza vital asexual de la niña.

Sin embargo, me parece que no toda interacción con un sujeto masculino termina en tragedia. El poema La niña de la lámpara azul es el más emblemático de la obra de Eguren, pues refleja el leitmotiv del poeta. En este nuevamente aparece la niña como protagonista, pero aquí es ella quien se acerca y ofrece guiar a la voz poética masculina. En un fragmento se lee:

Con voz infantil y melodiosa

con fresco aroma de abedul,

habla de una vida milagrosa

la niña de la lámpara azul.Con cálidos ojos de dulzura

y besos de amor matutino,

me ofrece la bella criatura

un mágico y celeste caminoDe encantación en un derroche,

hiende leda, vaporoso tul;

y me guía a través de la noche

la niña de la lámpara azul.

Al igual que la crítica literaria, identifico a esta voz poética masculina con el propio Eguren, pues es él mismo quien explora ese camino maravilloso, mágico y celestial en toda su obra literaria y plástica. Al mismo tiempo, encuentro que la niña es el cuerpo y la identidad que le permiten dicha exploración, pues ella encarna el placer lúdico que forma parte de la erótica asexual.

Reflexionar sobre la obra de Eguren me deja con una tierna nostalgia y algo de amargura. En la poesía, la fantasía del juego se abre paso triunfante. En la realidad, sin embargo, se encuentra flanqueada. Tiene lugar en la infancia, pero es cuestionada o rechazada en la adultez al ser considerada inmadura o dañada.

La sexualidad es también un constructo social y una herramienta de biopoder que puede ser usada para invalidar, discriminar y patologizar individuos. Espero que hablar de eróticas nos permita entender y explorar distintas formas de placer sexual y asexual sin etiquetarlas de maduras o inmaduras, normales o desviadas, superiores o inferiores. Sentir vergüenza o culpa por disfrutarlas no tiene sentido. Las pasiones inmaduras simplemente no existen.

Estef Calderón (elle/they/them) is a PhD student in Hispanic Language & Literatures at Boston University. Their interests include the study of queer and female subjectivities in Peruvian poetry and film, role-playing games, watercolor painting, and photography. Email: estefcv@bu.edu

Estef Calderón (elle/they/them) es estudiante de doctorado de Hispanic Language & Literatures en Boston University. Entre sus intereses está el estudio de subjetividades femeninas y queer en la poesía y el cine peruanos, los juegos de rol, la pintura con acuarelas y la fotografía. Correo: estefcv@bu.edu

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

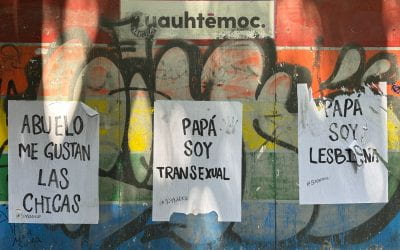

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.