The Eye that Cries: Peru’s Unreconciled Memories

In Lima, Peru, in the midst of Campo de Marte, a public park named after the god of war, a Zen space for reflection is guarded by a cast iron fence. El Ojo que Llora (“The Eye that Cries”)—the sculpture created by Dutch artist Lika Mutal to commemorate the victims of Peru’s armed conflict over the last two decades of the 20th century—is only accessible by special appointment or during certain days of remembrance, such as El día de los muertos or the anniversary of the report of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Acts of vandalism that started about a year after the inauguration of the monument in 2006, demanded strong measures to protect its integrity.

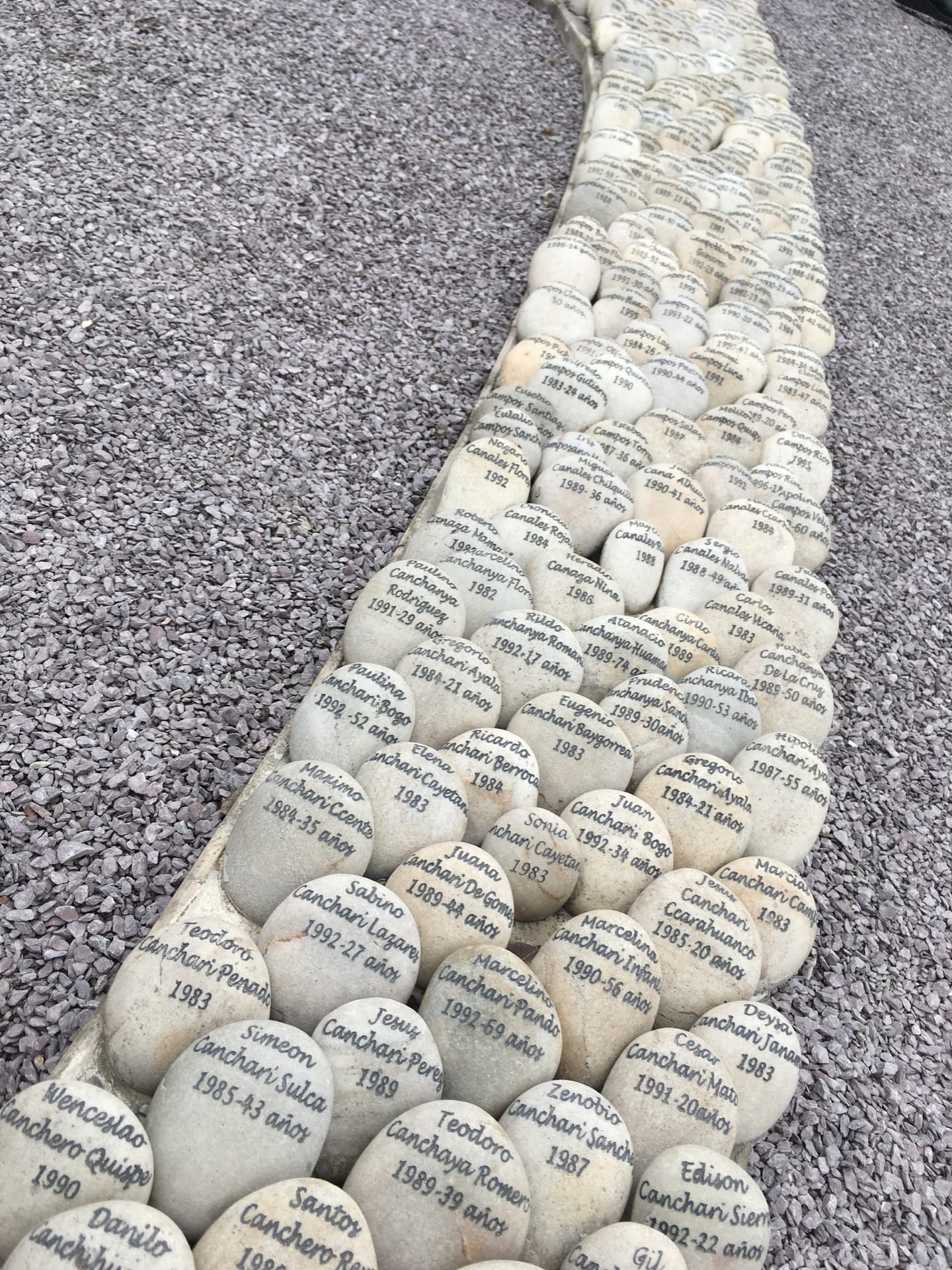

On special occasions, the relatives of those killed or disappeared during the war walk the paths of round stones marked with the names of the victims of both terrorism and state repression, deposit flowers and gather around the sculpture to perform rites of mourning or to participate in political demonstrations. But the iron fence and the restricted access to what is one of the most important memory sites for the victims of the violence between the Shining Path and the Peruvian government have become necessary measures to prevent vandalism. Supporters of Alberto Fujimori— the ex-president, now serving a 25-year prison sentence for corruption and human rights violations—deny his government’s role in the killings of thousands of Peruvians and have attempted to deface the monument to show their support for the country’s disgraced former leader.

Lika Mutal did not think her intervention would be controversial. She created a sculpture that, in her view, offered a space for healing. However, El Ojo que Llora became the center of political disputes when in 2006 the Inter-American Court of Human Rights declared that—as part of the country’s reparations for the military’s massacre of inmates at the Miguel Castro Castro penitentiary—the names of those killed there should be incorporated into the monument. This decision created bitter disputes over who qualifies as victims and how to memorialize them. Mutal, had, without her knowledge, already included the names of those killed in Castro Castro —who were in prison on charges of terrorism—because their names were in the original list of confirmed victims compiled by the Peruvian TRC. The ethical and judicial controversies around “the victim” are central to the understanding of the conflicts that have impacted the role of this memorial in the national memory battles. Initially conceived as a space for peaceful reflection, the monument is now part of the bitter disputes that divide the country to this day.

When she took on this project, Mutal had been moved by the shocking findings of the TRC: over 69,000 Peruvians were killed during the two decades of the war between the Shining Path and the Peruvian armed forces and during that period the state and the majority of the public had not acknowledged that loss. The 2003 TRC’s photo exhibit, Yuyanapaq: To Remember, was extremely effective in conveying the atrocity that the most privileged sectors of the country had ignored. Mutal, like other artists and activists, wanted to use her talents to honor the suffering of the victims. She was inspired by the indigenous respect for the earth as the goddess Pachamama and represented her by a large irregular rock that has a small stone attached to the upper part. Water drips out of that “eye” into a small reflecting pool: Mother Earth crying for her fallen children. The center sculpture is surrounded by a labyrinth made of rounded stones inscribed with the names of the victims and the year they were killed.

The labyrinth is fashioned after the one in the Chartres Cathedral, a space for walking meditation. Different traditions connect the labyrinth design to practices in which walking on a single path exerts a calming effect, a leveling of the breath, and the lowering of the heart rate. Mutal had envisioned a site that would invite a pilgrimage of forgiveness and reconciliation within oneself and with others. However, the beautiful space she created could not be separated from the political tensions of the day: were the 69,000 dead victims of terrorism or a result of both terrorist acts and state violence? Was this a civil war? An ‘internal armed conflict’? No term was seen as neutral. All of them were perceived as ideologically charged.

El ojo que llora became particularly entangled in the discussions surrounding the concept of “the victim”: Can somebody who has committed crimes against humanity also be a victim? Or can we only consider victims those who can be constructed as “innocent victims”? Mutal herself became unsettled by these disputes, initially responding that it had not been her intention to memorialize “terrorists.” Some relatives of victims of the Shining Path were outraged to learn that members of that organization were being remembered in the same space as their loved ones. In a turbulent environment in which the TRC was trying to make sense of the tragedy that the country had been through, their understanding of who could be considered a victim changed and adapted, which explains the inconsistencies of who was counted as a victim at different times in the process. When the Peruvian “Registro único de víctimas”—the official registry of victims whose relatives were entitled to reparations— was finally established it did not include “members of subversive organizations,” but did count members of the armed forces who died in combat. However, those widowed or orphaned by the violent actions of the state also claim a place to mourn and pleaded for the names of their loved ones not to be removed from the monument.

The United Nations and international human rights organizations support a non-discriminatory understanding of victims, defined by the U.N. High Commission of Human Rights as “persons who, individually or collectively, have suffered harm, including physical or mental injury, emotional suffering, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights, through acts or omissions that do not yet constitute violations of national criminal laws but of internationally recognized norms relating to human rights.” Mutal’s hesitation over memorializing members of the Shining Path reflects deep divides within the country. The TRC itself struggled in its own understanding of “the victim,” pressed by the state position that members of the armed forces and defense committees died serving the country while members of the Shining Path were enemies of the nation.

However, it was also important to recognize that some members of the Shining Path, like those killed in Castro Castro, had their most essential human rights violated: many had been victims of torture and many died in extrajudicial killings. Caught in that embattled scenario, El ojo que llora has suffered numerous attacks, including forms of vandalism that overtly signaled alliance with Alberto Fujimori, such as covering the monument in orange paint, the color of Fujimori’s party. As I write this piece during June of 2021, Peruvian citizens are again divided by a polarized election between Keiko Fujimori (the daughter of the incarcerated ex-president) and Pedro Castillo (a leftist union leader). Although Pedro Castillo has won the election by a slight margin, supporters of Keiko Fujimori refuse to accept this result two weeks after the defining vote, threatening the future of democracy for the country. El ojo que llora is again at the center of controversy over declarations by a member of Keiko Fujimori’s party, which prompted a statement in the monument’s defense by Caminos de la memoria, a group dedicated to preserving its role in Peru’s political history.

As Argentine sociologist Elizabeth Jelin and other experts on commemorations of social trauma have stated, memory sites acquire a life of their own, often divorced from the intentions of those who created them. Memory sites work as a way to institutionalize a specific way of retelling history, but the practices around the monuments do not always align with the spirit in which they were created. Lika Mutal received support for her work as it was conceived during the brief transitional period when the TRC investigated the crimes and published its report. The subsequent battles around the meaning of Mutal’s sculpture, however, were a result of contentious political factions regaining strength after that brief term in the early 2000s when Peruvians initially seemed intent on reconciliation. The attempts to end polarization have been doomed, as witnessed by the hateful language sparked by the recent elections.

However, both the attacks to the monument and its appeal for those who visit it speak to its symbolic power. El Ojo que llora has in fact become a polarizing symbol for some, but it has also become a site of mourning and even a place for the education of younger generations. Even with its restricted access, the monument occupies an important space in the Peruvian imagination, not only because of the political divisions it conjures, but because of its aesthetic qualities and evocative mechanisms. It has inspired other memory sites around the country such as the one in the Toraya community in southwestern Peru, which replicates the idea of the crying stone and the surrounding labyrinth of names.

The harmony Ojo que Llora establishes between its vertical boulder and its surrounding horizontal labyrinth captivates our senses and appeals to our emotions. Its fractals and austere symmetry foster relaxed contemplation and a connection to the earth, and Mutal’s use of natural materials, stones and water, symbolizes a return to nature that leaves behind the violence of a “bad death,” caused by political violence. These aesthetic elements, very different from most monuments celebrating war heroes, invite general viewers into the space, which makes its restricted access tragically ironic.

Notwithstanding these restrictions, the monument carries out its different roles in the battles for contested memories. El Ojo que Llora is for many the headstone for the absent body of their loved one. Many of the names inscribed in Lika Mutal’s memorial refer to people whose bodies were never found. Without a place to remember their dead, relatives of the victims flock to this site to honor their memory. But, as in other monuments that inscribe the names of the fallen, this list of names activates different forms of affect. Reading the name of a person along with the date of their death or their age at the time of their killing, makes us think of their life, of the reality of a person’s lived experience cut short by violence, even if we never met that person.

While the name itself does not evoke the same affect in the general public as it does for a friend or relative, any visitor understands the sense of the loss of a person. But the list of names also impacts the viewers with the sense of the accumulation, the shock caused by the sheer number of the dead. As with other memorials, such as Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial or the Parque de la Memoria in Buenos Aires, the spectator is confronted with a seemingly infinite number of deaths, in which each individual loss adds to the dimension of the tragedy.

Beyond Lika Mutal’s initial intentions, the mandate by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the debates surrounding the judicial and ethical idea of the victim, and the efforts of Fujimori’s followers to destroy the monument, El Ojo que Llora has become a strong actor in the memory battles of an unreconciled nation. Although some Peruvians claim the need to look to the future and leave the past behind, many open wounds reveal that the country cannot move forward without addressing the deep differences that led to the war between the Shining Path and the state in the first place.

While neoliberal forces stress economic development as the nation’s panacea, the same areas of the country that suffered the most during the war are now areas where environmentally destructive mining and development are contaminating essential water sources. The extreme economic difference that radicalized members of the Shining Path, are also seen in the devastation caused by Covid-19. Pachamama keeps crying for her dead children and Peruvians keep struggling, unable to agree on who is worth mourning and how to commemorate them.

El ojo que llora

Memorias irreconciliables en el contexto peruano

Por Margarita Saona

En Lima, Perú, en el medio del Campo de Marte, un parque dedicado al dios de la guerra, se alza un espacio Zen de meditación resguardado por una reja de hierro forjado. El ojo que llora, la escultura creada por la artista holandesa Lika Mutal para conmemorar a las víctimas del conflicto armado interno peruano de las últimas dos décadas del siglo XX, no puede visitarse sin previa cita, excepto durante fechas especiales como el día de los muertos o el aniversario de la entrega del reporte de la Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación (CVR). El monumento fue inaugurado en el año 2006, pero poco tiempo después los actos de vandalismo que buscaban destruirlo o mancharlo obligaron a tomar medidas de seguridad para proteger su integridad.

En ocasiones especiales, los familiares de aquellos asesinados o desaparecidos durante la guerra caminan por los caminos de canto rodado en los que cada piedra está inscrita con los nombres de las víctimas tanto del terrorismo como de la represión del estado. En esas fechas depositan flores sobre las piedras y se reúnen alrededor de la escultura para ceremonias de duelo o para llevar a cabo demostraciones políticas demandando justicia. La reja de hierro y el acceso restringido se han vuelto medidas necesarias para proteger uno de los más importantes memoriales a las víctimas de la violencia entre Sendero Luminoso y las fuerzas del gobierno peruano. Los seguidores de Alberto Fujimori—el ex-presidente que hoy sirve 25 años en prisión por corrupción y violación a los derechos humanos —niegan el papel de su gobierno en la muerte de miles de peruanos y han intentado en varias ocasiones destruir el monumento en su afán de mostrar su apoyo al desprestigiado jefe de estado.

Lika Mutal no se imaginaba que su proyecto se convertiría en un símbolo controversial. Había creado lo que para ella era un lugar de sanación. Sin embargo, en 2006 El ojo que llora se convirtió en el centro de disputas políticas cuando la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos declaró que, como parte de las reparaciones que el país debía ofrecer a las víctimas de la masacre en la penitenciaría Miguel Castro-Castro, los nombres de aquellos asesinados en dicha masacre debían incorporarse a los conmemorados por la escultura de Mutal. Tal decisión creó amargos conflictos acerca de la definición de víctima y cómo memorializar a quienes a su vez habían cometido violaciones de derechos humanos. Mutal, sin saberlo, ya había incluido a aquellos muertos en Castro-Castro, que estaban en prisión bajo cargos de terrorismo, porque sus nombres estaban en la lista original de muertes confirmada por la CVR. Las controversias éticas y jurídicas acerca de “la víctima” son centrales para entender los conflictos que han impactado el papel que juega este memorial en las batallas por la memoria del país. Concebido inicialmente como un espacio de reflexión pacífica, el monumento se ha vuelto parte de las amargas disputas que dividen al país hasta el día de hoy.

Cuando inició el proyecto, Mutal lo hizo conmovida por los impactantes resultados de las investigaciones de la CVR: más de 69, 000 peruanos fueron asesinados durante las dos décadas de la guerra entre el gobierno y Sendero Luminoso y, lo que es más, la mayoría del país había permanecido indiferente ante dicha pérdida. La exhibición fotográfica Yuyanapaq: Para recordar auspiciada por la CVR en 2003 fue un medio extremadamente efectivo para presentar las atrocidades que los sectores más privilegiados del país habían ignorado. Mutal, como otras artistas y activistas, querían usar sus talentos para honrar el sufrimiento de las víctimas. Inspirada por el culto indígena a la tierra, la diosa Pachamama, la representó por medio de una gran roca irregular que tiene una pequeña piedra a modo de ojo en la parte superior. De este “ojo” brota agua que fluye por la piedra hasta una pequeña fuente: la Madre Tierra llora por sus hijos caídos. El centro de la escultura, donde está Pachamama, está rodeado por un laberinto hecho de cantos rodados en los que se leen los nombres de las víctimas y el año de su defunción.

El laberinto de Mutal está inspirado en el de la Catedral de Chartres: es un espacio para meditar caminando. Distintas tradiciones conectan el diseño del laberinto a prácticas en las que caminar por un sendero produce un efecto relajante, regulando la respiración y disminuyendo el ritmo cardiaco. Mutal imaginó un sitio que invitara a un peregrinaje de perdón y reconciliación con uno mismo y con los otros. Sin embargo, el hermoso lugar que creó no pudo separarse de las tensiones políticas de su tiempo: ¿las 69,000 víctimas fueron asesinadas únicamente por terroristas o por también por la violencia del estado? ¿Se trató de una defensa de la nación frente a fuerzas terroristas? ¿De una guerra civil? ¿De un conflicto armado interno? Ningún término era neutral. Todos ellos venían con una clara carga ideológica.

El ojo que llora terminó especialmente involucrado en las discusiones respecto del concepto de “la víctima”. ¿Podría alguien que hubiera cometido crímenes contra la humanidad ser una víctima al mismo tiempo? ¿O solamente se debía calificar de víctimas a quienes eran presentados como “víctimas inocentes”? La propia Mutal expresó su consternación a raíz de las disputas, respondiendo inicialmente que no había sido su intención memorializar a “terroristas”. Algunos parientes de víctimas de Sendero Luminoso se indignaron al descubrir que miembros de dicha organización habían sido memorializados en el mismo espacio que sus seres queridos.

En el turbulento ambiente en el que la CVR estaba tratando de entender la tragedia que había asolado al país, sus nociones de quién podría ser considerado víctima cambiaron y se adaptaron más de una vez, lo que explica las inconsistencias en las listas de víctimas en distintos momentos del proceso. Cuando se creó un a nivel nacional un “Registro único de víctimas” que determinaba quiénes entre los sobrevivientes tenían derecho a reparaciones, éste no incluyó a “miembros de organizaciones subversivas”, pero sí a miembros de las fuerzas armadas que habían muerto en combate. Sin embargo, quienes habían perdido a su pareja o a su padre o a su madre por las acciones violentas del estado también reclamaban un lugar para ofrecer el duelo por sus muertos y pedían que los nombres de sus seres queridos no fueran borrados del monumento.

Tanto las Naciones Unidas como otras organizaciones internacionales que defienden los derechos humanos apoyan una definición no-discriminatoria de las víctimas. Una “víctima” es definida por la Alta Comisión de Derechos Humanos de las Naciones Unidas como “personas que, individual o colectivamente, hayan sufrido daño, incluyendo perjuicios físicos o mentales, sufrimiento emocional, pérdidas económicas o un impedimento substancial a sus derechos fundamentales por actos u omisiones que no llegan a constituir crímenes según las leyes nacionales, pero sí violan las normas de derechos humanos reconocidas internacionalmente “. () Los escrúpulos de Mutal con respecto a la memorialización de miembros de Sendero Luminoso refleja las profundas divisiones de la nación. La CVR misma tenía conflictos en su propia definición de “víctima”, ante la posición del estado de que los miembros de las fuerzas armadas habían muerto en servicio de la patria en tanto que los miembros de Sendero Luminoso eran enemigos de la nación.

Sin embargo, era imperativo reconocer que algunos miembros de Sendero Luminoso, como aquellos asesinados en Castro Castro, habían sufrido violaciones a los derechos humanos más esenciales. Muchos habían sido torturados o asesinados extrajudicialmente. En medio de ese escenario plagado de antagonismos, El ojo que llora ha sufrido numerosos ataques, incluyendo formas de vandalismo que delatan abiertamente la alianza de los responsables con Alberto Fujimori al cubrir la estatua con pintura naranja, el color de su partido. Al momento de escribir este texto en julio de 2021, los peruanos están divididos por una elección que polarizó a la población entre Keiko Fujimori, hija del ex-presidente encarcelado, y Pedro Castillo, líder sindical de izquierda. Pedro Castillo ha ganado las elecciones por un pequeño margen, pero los seguidores de Fujimori se rehúsan a aceptar este resultado, a pesar de que ha sido legitimado por observadores internacionales, amenazando el futuro democrático del país con esta negativa a aceptar el mandato popular. El ojo que llora ha vuelto a estar en el centro de controversias debido a declaraciones de un miembro del partido fujimorista. Caminos de la memoria, un grupo dedicado a preservar el rol de El ojo que llora en la historia política peruana ha promulgado un manifiesto en defensa del monumento.

La socióloga argentina Elizabeth Jelin y otros expertos en las conmemoraciones de trauma social ha declarado que los sitios de memoria adquieren una vida propia, con frecuencia divorciada de las intenciones de quienes los crearon. Los sitios de memoria son una forma de institucionalizar una forma específica de contar la historia, pero las prácticas que se generan alrededor de los monumentos no siempre se alinean con el espíritu en que fueron creados. Lika Mutal recibió apoyo para su trabajo tal como fue concebido durante el breve periodo transicional en el que la CVR estaba investigando los años de la violencia y acababa de publicar su reporte. Las batalles que siguieron disputando el sentido de la escultura de Mutal fueron, sin embargo, el resultado de facciones políticas contenciosas que ganaron fuerza después de esos años al iniciar el milenio cuando los peruanos parecían inclinados a buscar una reconciliación. Los intentos de terminar las divisiones del país fracasaron, como puede constatarse en el lenguaje abiertamente hostil y violento desatado por las recientes elecciones.

Es importante recalcar, sin embargo, que tanto los ataques al monumento como las declaraciones en su defensa son testimonio de su poder simbólico. El Ojo que llora se ha convertido en la práctica en un símbolo polarizante, pero también es un lugar de duelo para muchos e, incluso, un espacio educativo para las generaciones más jóvenes. Aunque su acceso sea restringido, el monumento ocupa un lugar importante en el imaginario peruano, no solamente por las divisiones políticas que conjura, sino también por sus cualidades estéticas y su capacidad de evocación. La escultura de Mutal ha inspirado otros lugares de memoria en el país, como, por ejemplo, el de la comunidad de Toraya en el suroeste peruano, que replica la idea de la piedra que llora rodeada por un laberinto de nombres.

La armonía que el Ojo que llora establece entre la roca vertical en el centro y el laberinto horizontal que la rodea cautiva nuestros sentidos y apela a nuestras emociones. El uso de fractales y la austera simetría que lo conforman conducen a la contemplación y al sentido de una conexión con la tierra gracias al uso de materiales naturales tales como las piedras y el agua y simboliza un retorno a la naturaleza que deja atrás la violencia de la “mala muerte” causada por la violencia política. Estos elementos estéticos, muy diferentes de la mayoría de monumentos que celebran a los héroes de la guerra, invitan a los visitantes a este espacio que debería ser abierto, lo que hace del restringido acceso una trágica ironía.

A pesar de las restricciones, el monumento continúa cumpliendo importantes roles en las disputadas batallas por la memoria. Para muchos El Ojo que llora es la lápida del cuerpo ausente de la persona amada que fue desaparecida. Muchos de los nombres recogidos en el memorial de Lika Mutal se refieren a personas cuyos cuerpos nunca fueron encontrados. Como en otros monumentos que inscriben los nombres de los caídos en un conflicto armado, la lista de nombres activa diferentes formas de afecto. Leer el nombre de una persona junto a la fecha de su muerte o junto a la edad que tenía al momento de morir nos lleva a imaginar su vida, la realidad de la experiencia vivida por una persona cuya vida fue interrumpida tempranamente por la violencia, incluso si esa persona nos es desconocida.

Mientras que el nombre de por sí no causa el mismo efecto en el público general que en un pariente o una persona cercana, cualquier visitante puede entender la sensación de pérdida de una vida humana. Pero la lista de nombres también nos impacta por su efecto acumulativo, el número excesivo de los muertos. Como con otros memoriales, tales como el Memorial de los veteranos de Vietnam de Maya Lin o el Parque de la Memoria en Buenos Aires, los espectadores se enfrentan a lo que parece ser un número infinito de muertes en el que cada pérdida individual incrementa la dimensión de la tragedia.

Más allá de las intenciones iniciales de Lika Mutal, el mandato de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, los debates en torno a la figura ética y jurídica de la víctima y de los esfuerzos de los fujimoristas de destruir el monumento, El Ojo que llora se ha convertido en un actor principal en las batallas de la nación irreconciliable. Aunque algunos peruanos insisten en que es necesario mirar al futro y dejar el pasado atrás, muchas heridas abiertas revelan la imposibilidad del país de progresar sin atender las hondas diferencias que condujeron a la guerra entre Sendero Luminoso y el estado.

Mientras que las fuerzas neoliberales enfatizan el desarrollo económico de la nación como una panacea, las mismas áreas del país que sufrieron lo peor durante la guerra son las que hoy sufren los efectos destructivos de la minería y el desarrollismo que contamina las fuentes esenciales del agua. Las diferencias económicas extremas que radicalizaron a los miembros de Sendero Luminoso pueden aun verse en la devastación causado por Covid-19 entre los más pobres. Pachamama sigue llorando por sus criaturas muertas mientras los peruanos siguen disputando, incapaces de concordar en quiénes merecen el luto ni en cómo conmemorarlos.

Margarita Saona teaches Latin American literature and cultural studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). She has published Memory Matters in Transitional Peru (Palgrave, 2014) among other works on literature, art and memory. She is currently working on a book on illness entitled Vital Signs. saona@uic.edu, @margaritasaona, https://margaritasaona.academia.edu/

Margarita Saona enseña literatura latinoamericana y estudios culturales en la Universidad de Illinois en Chicago (UIC). Ha publicado Memory Matters in Transitional Peru (Palgrave, 2014) traducido al español como Los mecanismos de la memoria: Recordar la violencia en el Perú (Fondo Editorial PUCP, 2017) entre otros trabajos sobre literatura, arte y memoria. Actualmente está trabajando en un libro sobre la enfermedad titulado Signos Vitales. saona@uic.edu, @margaritasaona, https://margaritasaona.academia.edu/

Related Articles

The Eye that Cries: Peru’s Unreconciled Memories

English + Español

In Lima, Peru, in the midst of Campo de Marte, a public park named after the god of war, a Zen space for reflection is guarded by a cast iron fence. El Ojo que Llora (“The Eye that Cries”…

Editor’s Letter: Monuments and Counter-Monuments

Cuba may be the only country on the planet that sports statues of John Lennon and Vladimir Lenin. Uruguay may be the first in planning a full-fledged monument to the victims of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A Monumental Battle for the Story of Texas

In 2016, I visited the Alamo, as part of my first real return to Texas in many years. I had mapped out a road trip with my brother Edmund Roberts. Though Edmund has long known of…