About the Author

Pedro Francisco Vormittag is a lawyer and the Chief of Staff to the Presidency of the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI). A sustainable development activist, Pedro holds a Master of International Affairs from Columbia University and a Master in International Management degree from the São Paulo School of Business Administration of Fundação Getulio Vargas in Brazil.

A breeze of politics

I was an international observer to the Organization of American States (OAS) Electoral Observation Mission in the Honduran general elections in 2021 as a student at the School of International Affairs at Columbia University. What I witnessed taught me to appreciate how the nuts and bolts of democratic development might be noisy and messy, but successful nonetheless.

As I stepped out of the plane at Ramón Villeda Morales International Airport in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, the breeze that rushed through me felt like home. But despite the similarity with Brazil, I had been told not to feel comfortable: for many years the city of San Pedro Sula was considered the world capital of murder, with the highest number of homicides outside war zones.

Less than 24 hours before landing, I was in New York with no greater concern than submitting my microeconomics problem sets on time. But now, as the city’s Chief of the National Police welcomed us through a diplomatic track to Immigration control, I couldn’t help but remember Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz: we were not in Kansas anymore.

In the run-up to the 2021 Honduran elections, more than 20 politicians had been murdered — mostly opposition leaders. The combination between politics and violence was not exclusive to Honduras, though. Earlier that very summer, the President of Haiti had been murdered. In neighboring Nicaragua, President Daniel Ortega put in jail seven rival candidates against his reelection bid, and President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador was known for claiming to be “the coolest dictator in the world” in his Twitter bio.

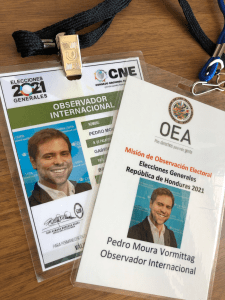

I was one of 50 international observers in the Electoral Observation Mission of the Organization of American States (OAS). Our goal was to verify if the election would show any sign of irregulatiries, such as those that damaged the legitimacy of the previous 2017 presidential election. Back then, among countless reports of irregularities, Honduras’ Electoral Court declared President Juan Orlando Hernández victorious even after the vote-counting system went down for five hours.

I was one of 50 international observers in the Electoral Observation Mission of the Organization of American States (OAS). Our goal was to verify if the election would show any sign of irregulatiries, such as those that damaged the legitimacy of the previous 2017 presidential election. Back then, among countless reports of irregularities, Honduras’ Electoral Court declared President Juan Orlando Hernández victorious even after the vote-counting system went down for five hours.

Under the protection of armored National Police escort, an official OAS convoy drove me and my Columbia colleagues from Peru, Colombia and Brazil through a 4-hour trip from San Pedro to Tegucigalpa, the capital. At the hotel where the Mission established its headquarters, experts taught me and my Columbia colleagues from Peru, Colombia and Brazil about Honduran electoral legislation, the operational bottlenecks for that Sunday’s election and a bit of country’s recent political history. Security briefings taught us how to remain safe if the vote-counting procedure triggered violent demonstrations in the streets. In the 2017 elections, at least 30 Honduran citizens had been killed in confrontations with military and police forces after thousands took the streets to protest against the Electoral Court’s decision.

I was assigned to go back to San Pedro Sula to observe voting in the Lomas del Carmen neighborhood, where just months before the police had arrested one of the leaders of the Mara Salvatrucha gang, the strongest criminal organization in Honduras. San Pedro and that community in particular were among the crucial regions for the most well-performing opposition candidate.

Our SUV struggled to find a way to climb that steep unpaved road that led to Rafael Leonardo Callejas School, where the voting station I was stationed would be installed. Unaware of the stakes, an enormous pig blocked our away to the street the car’s GPS suggested as an entrance to the school. It took us the remainder of that Saturday’s afternoon to figure out another way uphill. Until the neighbors and business people in the block finally showed us a route has as steep but paved and unblocked. On our arrival, locals offered our team a taste typical Honduran baleadas, a sort of tortilla with brown beans and cheese fillings. On top of that hill, I enjoyed the breeze while hearing people’s take on the political moment of the country.

And then Sunday came. The weather was among the hottest I have ever felt to this day. But before the crack of dawn, we were ready at our stations. People pourted into the voting rooms as soon as the school opened its gates. At each voting booth, auditors appointed by the three largest competing political parties would rush to certify ballots, check IDs and audit signatures.

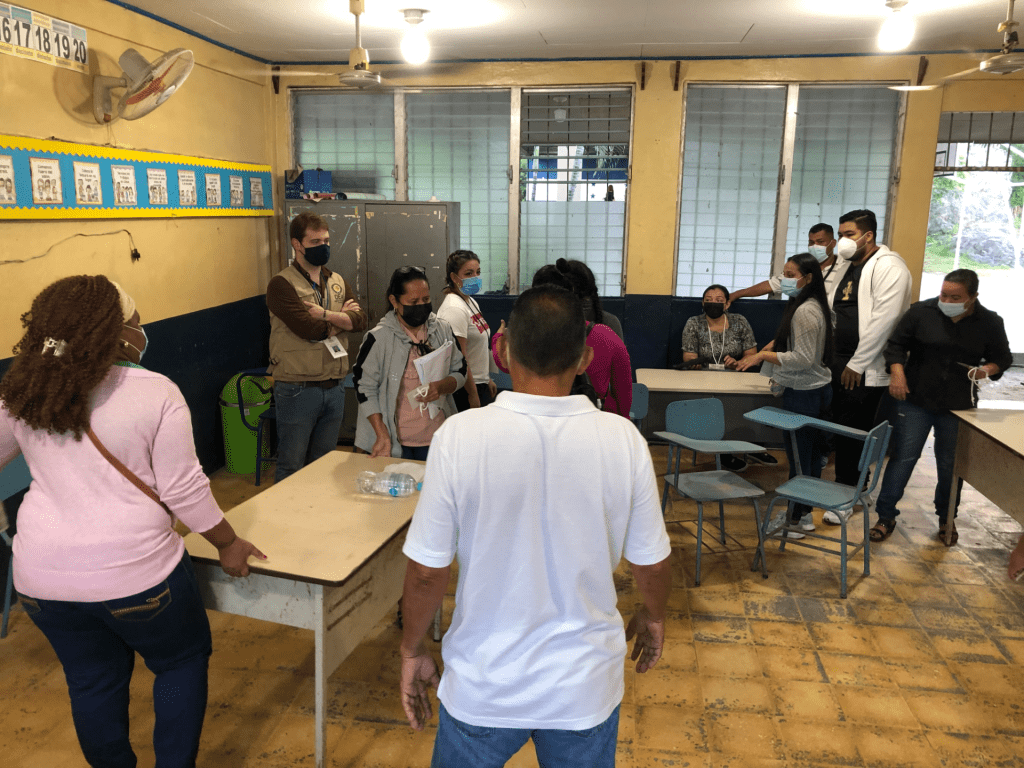

Over the afternoon, I visited seven schools and observed voting procedures in almost 60 Juntas Receptoras de Votos (JRVs), the voting booths for each electoral precinct. In some of them, there was some hostility between supporters of rival parties asking for votes, but not enough to disturb voter flow in any meaningful way. I made sure to report on whatever issues the Head of the Mission could consider problematic. My job was to observe and never interfere.

As the ballot boxes closed, the critical moment began.

The schools that served as voting venues earlier that day were also tasked with hosting the vote counting procedure, and each JRV should report the number of votes for each candidate by the end of that night.

My job was to carefully observe such ritual. In the evening, supporters of all candidates rushed back into the school, classroom turned into soccer arenas. Following previously established rules, the representatives of each party locked the doors of the classrooms, as classrooms as hundreds of supporters from all parties rallied at their doors and windows, amping up the pressure for the ballots to be counted correctly.

Like a soccer match, supportes from each team would shout at their athletes — and, primarily, at the referees. Inside each classroom, I tried to keep one eye in that loud ranting, another eye in the accuracy of the vote counting.

What I witnessed was a flawed, but honest attempt to realize democracy on the ground. As I heard and saw the emotion driving each announcement by the auditors and people’s reaction to it, I couldn’t help but remember my experience involved in elections myself — as a political party officer, as a supporter for a candidate, or even as a candidate myself. Democratic politics can sometimes be messy and noisy.

On that Sunday, nobody felt the need to riot on the streets of San Pedro Sula. Honduras had a new President, Xiomara Castro, the wife of former President Manuel Zelaya, who had been ousted on the 2009 coup that delved the country into the constitutional crisis it was struggling to overcome. She would be Honduras’ first woman president.

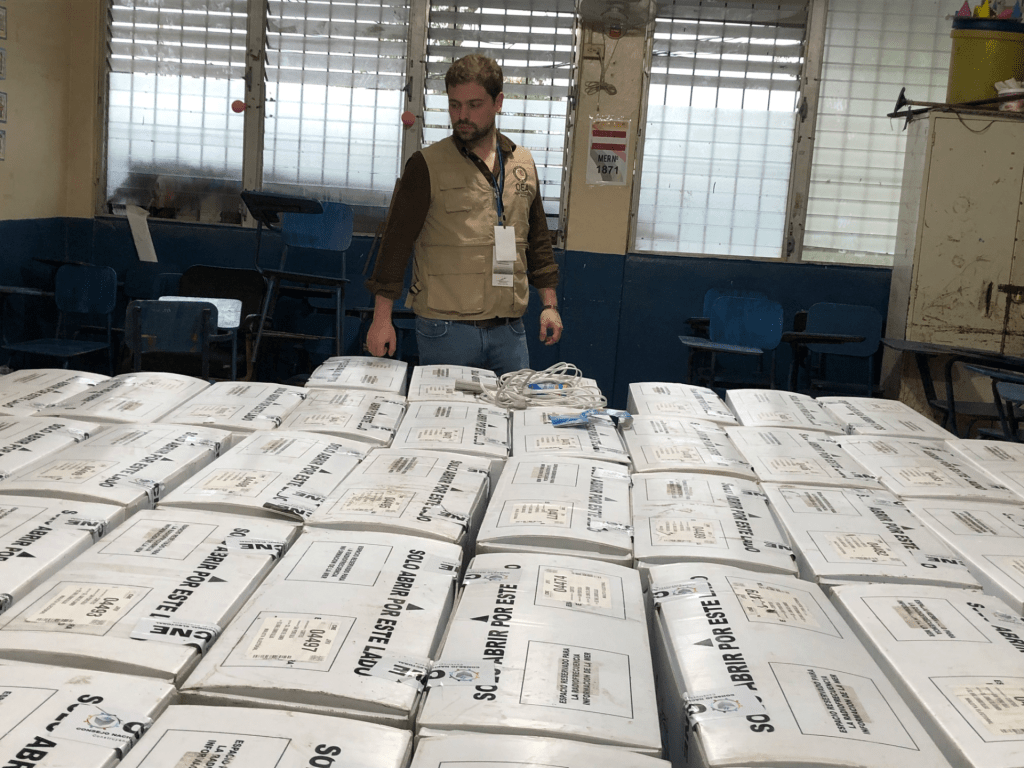

The day after, the votes cast across the region were gathered at the National Stadium in downtown San Pedro. At its wide indoor sports court, trucks unloaded thousands of ballot boxes under Army escort.

I flew back to New York by the end of that Thanksgiving holiday. As I returned to my daily life, I couldn’t help but think — and smile — of that noisy, messy part of the world where politics has potential to be more like soccer than like war.

Where that breeze flows is where I feel the most at home.

More Student Views

Colombian Women Who Empower Dreams

English + Español

The verraquera of Colombian women knows no bounds. This was the message left with me by the March 30 symposium, “Empowering Dreams: 1st symposium in honor to Colombian women at Harvard.”

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.

Resilience of the Human Spirit: Seizing Every Moment

In the heart of Chicago, where I grew up, amidst the towering shadows of adversity, the lingering shadows of generational demons and the aroma of temptation, the key to the gateway of resilience and determination was inherited. The streets of my childhood neighborhood became, for many, prisons of poverty, plundering, crime and poor opportunity.