A New Future for Ancient American Art in Today’s Museums

When I was a graduate student at Harvard studying the ancient Americas, I became acutely aware of how the campus’s museums were organized. Although I was earning my Ph.D. in the History of Art and Architecture, the objects I researched were not part of the Harvard Art Museums—the conjoined Fogg, Busch-Reisinger and Arthur M. Sackler Museums. Rather, they were stewarded by the separate Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. This division had myriad pedagogical consequences beyond the question of the nature of art. For one thing, the Peabody did not share in Renzo Piano’s glittering redesign of its peers that was then underway; however, I was ecstatic that its extraordinary collection was not consequently inaccessible. Through my research, I came to recognize the depth and breadth of the Peabody’s collection as one of Harvard’s greatest educational resources. Countless understudied objects in its care decisively shaped my dissertation and the book that grew out of it, Scale & the Incas (Princeton University Press, 2018).

I was thinking a lot about scale during those years. The Peabody collection has many Andean artifacts that have been categorized as miniatures, or perhaps children’s toys, and my research sought to understand why. But scale is an issue that has also defined museums as institutions. The goal of creating an “encyclopedic museum” is wrapped up in the notion of somehow reproducing the world in microcosm. However, reductions in scale usually result in a loss of detail and scope. Certain elements get left out in the effort to distill and recreate the essence of a thing. As Harvard’s museums show, one way that would-be encyclopedic museums originally limited their purviews was by drawing a distinction between “Art” and “artifacts.” In principle, this was supposed to be an ontological differentiation in the kinds of objects an institution addressed; but in practice, it became more of a turf war between art museums and anthropology or natural history museums over regions of the world.

This historical shift is also evident at the Art Institute of Chicago, where I am now an associate curator of Arts of the Americas. Founded in 1879, this new museum for a new U.S. city needed old things. In those early years, the museum’s Greco-Roman sculptures were plaster casts—but Native American objects offered an authentic form of American antiquity. Thus, as early as 1889, the decade-old museum acquired a group of Ancestral Puebloan ceramics.

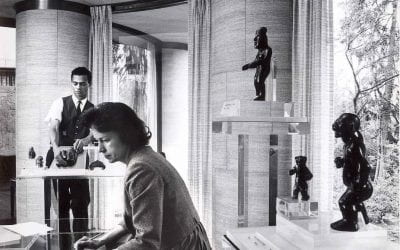

But 1893 brought to Chicago the World’s Columbian Exposition, which marked the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. The collections of Indigenous belongings amassed for the fair ultimately went to our neighbor, the Field Museum of Natural History. For the next sixty years, the Art Institute of Chicago largely refrained from acquiring Native American and Indigenous Latin American items. That only changed in the 1950s when several art museums in the United States began founding departments of what was then called “primitive art”—primarily Native and Indigenous American, African and Oceanic objects—in large part due to contemporary artists’ emerging interest in these artistic traditions. In 1955, the Art Institute of Chicago acquired German ophthalmologist Eduard Gaffron’s famed collection of ancient Andean artifacts, founding a department dedicated to preserving them in 1957. Native American and Indigenous Latin American art have been key components of the museum ever since.

The way art museums across the United States reversed course on exhibiting Native and Indigenous objects shows how arbitrary the distinction between “Art” and “artifact” always has been. In my view, what really distinguishes art museums from anthropology and natural history museums is not so much the nature of the objects presented, but a difference in institutional approach: art museums more often encourage audiences to consider issues like form, facture, skill and creativity.

Almost more than ancient Indigenous art, however, colonial Latin American art has more recently exposed the Victorian conceit of encyclopedic museums. Long regarded as second-rate European art or dismissed as the art of the colonizers, colonial Latin American art was often overlooked by art museums in the United States. But over the past three decades, copious scholarship and numerous exhibitions have shown that colonial Latin American art represents the crucial convergence of European art, indomitable Indigenous traditions and beliefs, and even—by way of the Manila galleons—reinterpretations of Asian art. Notably, one of the leading advocates for colonial Latin American art has not been a museum or university but the Carl and Marilynn Thoma Foundation, which has formed an unparalleled collection of colonial Andean paintings, while simultaneously funding an array of fellowships and grants to scholars and institutions. The challenge many museums now face is how to situate syncretic and multivalent works of colonial Latin America within their ingrained structures of galleries and departments.

At the Art Institute of Chicago, in 2020, we began to restructure the institution. We dismantled the Arts of Africa and the Americas Department that had been founded in 1957, as well as our American Art Department, and created a new continental African department that includes Egypt and a new hemispheric Americas department. It is understandably slower work to restructure galleries; but, in the spring of 2022, we debuted a suite of reinstalled galleries that include, for the first time, Native American artists like Maria Martinez (San Ildefonso) alongside American painters such as Georgia O’Keeffe. The slowest work of all, however, is reshaping the collection. For example, the Art Institute’s collection of Andean art has not grown substantially since the 1950s. That said, two recent acquisitions now on view in Gallery 136 give a sense of what I see as the path ahead:

Kukuli Velarde’s La Linda Nasca

Because of the Gaffron collection, the Art Institute stewards a large collection of vessels made by Nasca artists who lived on the south coast of Peru from around 200 BCE to 600 CE. Nasca art has been intensively studied by scholars for its complex iconography; but these intricate images can be difficult for museumgoers to parse and relate to.

However, in one the gallery’s three cases devoted to Nasca art, a substantial ceramic, La Linda Nasca, by Peruvian contemporary artist Kukuli Velarde now holds court. Created in 2011, the sculpture takes the form of a gigantic Nasca vessel shaped like a woman; indeed, its form is very similar to an ancient ceramic exhibited beside it. Velarde’s contemporary work samples many of the same motifs as its older companions, but it also introduces Christian iconography like a bejeweled metal halo.

Velarde created La Linda Nasca as part of her CORPUS series, which explored the festival of Corpus Christi in Cusco. Each June, fifteen statues of Catholic religious figures are carried on litters in a procession from the parish churches around Cusco to the central Plaza de Armas. There, they join the main cathedral’s most important statue of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, known as La Linda or “the beautiful one.” However, in highland communities, there has long been the belief that these figures might not be Christian at all, but rather Indigenous deities in disguise. A Quechua author named Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, writing in 1611, claimed that Saint James appeared and fought against the Incas as they tried to reclaim Cusco from the Spanish invaders. He said the Indigenous soldiers saw Santiago come down from the sky like lightning; so, from then on, they equated him with yllapa, or “lightning” in Quechua, which they came to understand as an anthropomorphic Inca god.

La Linda Nasca from the series CORPUS, 2011 Kukuli Velarde

Velarde’s sculptures reveal the statues of the Corpus Christi festival to be ancient Indigenous deities surviving in the present. In La Linda, Velarde unmasks the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception as a resplendent Nasca goddess—hence, her Indigenous and Christian attributes. But perhaps the most striking aspect of the sculpture is her lifelike face. Her gums and eyes appear uncannily moist. The effect is unsettling, a reaction Velarde perhaps tethers to these issues of colonial violence and Christianization. At the same time, the sense that the figure is alive suggests how many Andean people today may also feel such dual identities. As a result, I personally find La Linda to be unusually optimistic for Velarde’s body of work, because she has created a new sort of deity that affirms Indigenous survivance and recognizes that multiple identities can coexist in a person and in fact be something linda or beautiful.

To date, works from Velarde’s CORPUS series have most often been presented alongside each other in temporary exhibitions—including Kukuli Velarde: CORPUS, organized by the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art and the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. But, within a museum’s permanent collection, La Linda arguably makes a greater visual and critical impact, not alongside other works of contemporary art, but among the ancient artifacts that inspired the artist. The Art Institute of Chicago was fortunate to be able to debut Velarde’s ceramic adjacent to a colonial, Cuzqueña School painting of Santiago Mataindios by an unknown artist, generously on loan from the Thoma Foundation, which provided additional historical context. As such, La Linda Nasca creates a bridge through time, connecting ancient art and colonial art through contemporary art.

Kukuli Velarde’s La Linda Nasca exhibited with Nasca ceramics and Santiago Mataindios, loaned by the Thoma Foundation, in Gallery 136 of the Art Institute of Chicago

Ana De Orbegoso’s Neo-Huacos

Another strength of the former Gaffron collection are vessels made by Moche ceramists who lived on the north coast of what is now Peru from around 100 to 700 CE. Moches are famous for their stirrup spouts, iconography painted in very fine lines, and—perhaps most uniquely—vessels that seem to have been sculpted as portraits.

But, nestled inside a large case of Moche ceramics are now three gleaming metallic forms. The gold-, silver-, and copper-colored objects were created by Peruvian contemporary artist Ana De Orbegoso as part of her 2017 series ¿Y qué hacemos con nuestra historia? She calls these works Neo-Huacos. In Peru, ancient ceramics are often referred to as huacos. The name derives from the Quechua word huaca, which was used by the Incas to denote sacred objects or sites. Huaca has since been applied to non-Inca archaeological sites including the Moche temples of Huaca del Sol and Huaca de La Luna.

Neo-Huaco #3 from the series ¿Y qué hacemos con nuestra historia? (So What Do We Do with Our History?), 2017 Ana De Orbegoso

People who dug into these temples looking for treasures came to be called huaqueros, or looters, just as the pots they found were termed huacos. Such actions are now illegal, but for much of the 20th century “pot hunting” was a profession and a source of livelihood for many Andean people, especially those in poorer areas. In some cases, it may have been the primary way individuals engaged with their ancient heritage. Because these archaeological civilizations were not Christian and did not speak Spanish, some modern Peruvians may find it hard to personally identify with them. “So,” De Orbegoso asks, “what do we do with our history?”

Her “new huacos,” I think, offer something of an answer. De Orbegoso created these works during an artist residency at the Museo Larco in Lima, which preserves one of the most important collections of Moche ceramics in the world. There, De Orbegoso was able to come face-to-face with the museum’s collection of Moche portrait vessels. De Orbegoso’s sculptures have the recognizable shape of portrait vessels, replete with headcloths and ear ornaments, but are strikingly faceless. Their metallic surfaces call to mind the lust for gold and silver that played a major role in the conquests of Indigenous cultures of the Americas. They also emphasize the commoditization of Andean antiquities and the contemporary art market. But perhaps most importantly, their mirrored surfaces allow modern-day Peruvian viewers to gaze upon these “portrait vessels” and see their own reflections. In so doing, De Orbegoso’s art offers them a visual and material connection to their ancestors.

Three Neo-Huacos by Ana De Orbegoso exhibited with Moche ceramics in Gallery 136 of the Art Institute of Chicago

***

Museums once aimed to present audiences with rigid, linear progressions through enfiladed galleries that both spatially mapped and paternalistically taught series of cultural traditions and art historical-isms. But works like La Linda Nasca and the Neo-Huacos not only open the possibility of a more circular understanding of time but also a more circular intellectual exchange between artists, curators and museumgoers. Together, artifacts from the deep archaeological past, objects from more recent historical eras, and artworks presenting contemporary perspectives can create a rich sensory field that has the power to prompt reflections on the past and pose questions about the future.

Andrew James Hamilton is Associate Curator of Arts of the Americas at the Art Institute of Chicago. He helps steward art of the ancient Americas, colonial Latin American art, and contemporary Native and Indigenous art. He is also a lecturer in the History of Art at the University of Chicago. He is currently completing a book on the royal Inca tunic at Dumbarton Oaks.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.