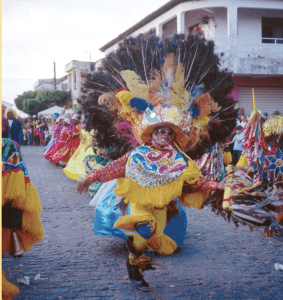

Caboclo Ritual Dance

Bringing the Juke-Joint into the Church

Caboclo dancing in Brazil: the figure of the caboclo spirit is the Brazilian equivalent of the traveling bluesman of the pre-1960s u.s. rural south–—improvising vernacular poets. Photo by Jason Gardener

To give oneself to dance is to experience the moving body as sacred. For anyone who believes that the alienation of the body from the spirit is simply an inevitable symptom of modernity, I offer a personal challenge: are you certain you’ve danced already? But if you have and remain unconvinced, I leave you with this mini-narrative about a peculiar type of ritual popular in urban Brazil. May it inspire your thoughts for the next dance!

Having assumed the body of his black female host, a Brazilian caboclo [a beloved class of ancestral spirits] saunters forward, cigar butt clenched between his teeth and leather cowboy hat tilted at a forward angle obscuring his eyes, and kneels dutifully before the atabaque drums. Grunting loudly and pounding his chest a few times, the caboclo Boadeiro (cowboy spirit) captures everyone’s attention and the room is suddenly silent. From a kneeling position, he chants a series of prayers (rezas) in a high-pitched nasal vocal timbre and is answered by the rapid ringing of a small two-toned iron bell. Finally, the caboclo offers his brethren a melody, to which they respond by alternating an enthusiastic chorus phrase with his solos. Boadeiro rises to his feet and suddenly—slap, slap, crack! Three drummers have entered forcefully to breathe life into the song, falling into an energizing rhythm punctuated by the syncopated tones and slaps of the lowest sounding instrument. Shuffling his feet in time as he sings solo verses, and gradually incorporating more rapid and extended leg and torso gestures during the chorus sections, Boadeiro begins to narrate his identity and personalized mythology through song and dance.

In a variety of popular religions in Brazil, rituals for the caboclos are a modern development with increasing participation from all segments of society. The boisterously social caboclo will possess the body of a spirit medium for several hours at a time, enabling people to know him through direct social interaction. In the state of Bahia, the spirits manifest as traditional songsters who smoke cigars, drink beer and the fiery liquor cachaça, dance, sing and offer proverbial wisdom from dusk until dawn. These caboclos tend to exude such charisma, creativity, distinctive personality and knowledge of regional culture that they become the “life of the party” and exemplars of Afro-Bahian social performance. Here’s a succinct analogy: the figure of the caboclo spirit is the Brazilian equivalent of the traveling bluesman of the pre-1960s rural American South—improvising black vernacular poets who sing personalized narratives and fragments of wisdom gathered from adventurous journeys. Metaphorically, they are like the mythologized Robert Johnson or Son House returning from the dead to invoke the juke joint, with all its profane and sacred meaning, right inside the church.

Boadeiro’s movements sometimes amplify his lyrical descriptions, through mimicry of popularly imagined Brazilian “Indians,” cowboys, and backwoodsmen or danced representations of their personalities—variously youthful and energetic, irreverent, humorous, crafty, provocative, creative and bold. Boadeiro’s arms gesture about in wide-open embraces, unlike the more graceful and self-contained orixás whose closed eyes and mouth, and careful positioning of the limbs are a physical manifestation of the body’s spiritual closure. The caboclo’s mouth is always opening—ingesting and emitting things, whether to sing, joke, drink beer, inhale or exhale smoke. The eyes of the spirit are wide open, staring, and rarely blinking. He kicks his feet and legs outward in various directions, sometimes propelling his body high in the air, or shuffling himself rapidly across the floor. Through the caboclo’s body, spiritual power is not tactfully restrained, but dramatically exhibited—or perhaps generated—through athletic movements, astonishing endurance, speedy footwork, and spontaneous delivery of one song after another.

Though Bahian caboclo ritual dances define a unique style of their own, I can trace relationships in the movements to other regional traditions including capoeira, samba-de-roda, coco and frevo. The caboclo’s virtuosic solo dancing, and intensely interactive exchanges with the lead drummer also bring to mind the street rumbas of Cuba. Yet these comparisons, obvious to an experienced local practitioner, are easily overlooked by foreign scholars. Perhaps one reason is that we assume “secular” activities—rumba, samba-de-roda and the other popular dances—do not involve religious content, or spirit possession. Looking for the sacred in the cities of Havana, Recife and Salvador, I’ve seen the African deity Chango at a Cuban rumba, coco house parties thrown for the spirits of Candomblé and even a mischievous caboclo seizing an unsuspecting medium in broad daylight at a Bahian samba-de-roda!

But before our readers mistake the trickster at the crossroads for an exotic demon, let me issue a reminder that the dancing, joking, and singing caboclo is a familiar, socially accessible, and virtuous character to Bahians. Hold on, blues people, I’m heading homeward for the coda: we can recognize that the Afro-American “ring shout” has been formally separated into the “ring” (popular dance) and the “shout” (religious dance), but I wouldn’t say that the sacred is absent from either. In the African Diaspora, modernity, dance and spirituality seem to get along quite nicely. To revisit the blues analogy, if the caboclo can “bring the juke joint into the church,” certainly it is possible to “get some religion at the Saturday night dance.”

Daniel Piper is a Ph.D. candidate in Ethnomusicology at Brown University. His current research in northeast Brazil focuses on the intersections of race and religious expression in regional dance music performance. Dan’s favorite dance is Cuba’s rueda-de-casino.

Related Articles

Disruption in the Immigrant Experience: Colombian Youth Dance Their Way to Continuity

Imagine you are fifteen years old. As an immigrant who has lived in the United States for a few years, you are still trying to find your place. You decide to join a group that dances the traditional dances of your country. You practice every week on Fridays, when you could be going to the movies or hanging out with your friends. Your goal is to perform in that big annual show a lot of people have told you about. That day has finally …

Review of Connecting Lines: New Poetry from Mexico

Lou Dobbs and other talk show hosts want us to believe that a so-called Mexican invasion is denying “true” Americans their jobs, democracy and destiny. Few among them comment on a peaceful, more subtle Mexican “invasion” that will help us see why fears of blending Mexican and U.S. culture are misplaced. One by one, since the turn of the century, anthologies of a Mexican poetry trumpeting innovation and diversity have been …

Review of The Hispanic World and American Intellectual Life, 1820-1880

Iván Jaksić’s highly original and engaging scholarship on the origins of U.S. academic interest in Ibero-America brilliantly reveals previously unknown trans-Atlantic and Western hemisphere intellectual networks. His research focuses on the life, interactions and contributions of those Jaksić calls“the pioneer American scholars and lifetime students of the Hispanic World”—Washington Irving, George Ticknor, Henry Wadsworth …