Latin America’s Gay Rights Revolution

Revisiting Out in the Periphery

My book Out in the Periphery heralded Latin America’s emergence as the “undisputed champion of gay rights in the Global South,” a momentous happening considering the region’s historic reputation as a bastion of Catholicism and machismo. At the time of the book’s publication in early 2016, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil and the “mini-state” of Mexico City had already legalized same-sex marriage, ahead of several countries that had led the world in advancing gay rights, including the United States, Britain and Germany. A handful of Latin American countries—including Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Colombia—had also introduced civil unions opened to same-sex couples.

Out in the Periphery by Omar G. Encarnación

No less important is that in 2016 Latin America had already experienced a transgender rights breakthrough. In 2011, only months after legalizing gay marriage, Argentina became the first country in the world to allow anyone to change the gender assigned at birth through a process known as gender self-identification. It allows anyone to change genders without permission from a judge or a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria. There did not have to be any surgical intervention to make this change. Last, but not least, by 2016 virtually every Latin American country had decriminalized homosexuality and many had or were in the process of enacting laws barring discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Since 2016, Latin America’s gay rights revolution has continued apace. By far, the most consequential development is the arrival of gay marriage in Chile and Cuba. For very different reasons, the coming of gay marriage to both countries marked a milestone for the progression of gay rights in the region. Chile has historically been one of Latin America’s most conservative countries, a reflection of the enormous political influence that the Catholic Church has historically wielded over Chilean legislators. It was only in 2004 that Chile legalized divorce, the last country in the Western Hemisphere to do so. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Chile had a harder time than neighboring Argentina and Brazil in legalizing gay marriage. The vote in the Chilean Congress that made gay marriage possible, in December 2021, under the conservative administration of Sebastián Piñera, was a culmination of a process that began 2017, when then-President Michelle Bachelet introduced the first gay marriage bill. That bill was defeated by conservatives closely affiliated with the hierarchy of the Catholic Church.

Cuba also stands out because the island’s politics remain staunchly undemocratic. This makes Cuba’s legalization of gay marriage in 2022—following the enactment of a new constitution that removed a definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman, and a popular referendum in which the Cuban people were asked to approve of gay marriage—a rare example of a non-democratic regime embracing gay rights. But just as notable is that the advent of gay marriage signals a striking shift in Cuba’s extremely dark history of oppressing homosexuals. The Cuban Revolution was notorious for its homophobia, stemming from the Marxist view of homosexuality as a sign of bourgeois decadence. In 1965, only a few years since the consolidation of Fidel Castro’s revolutionary regime, the Cuban government created the Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción, a network of labor camps for “social undesirables,” including political dissidents, prostitutes, drug-users and homosexuals.

In 1965, only a few years since the consolidation of Fidel Castro’s revolutionary regime, the Cuban government created the Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción, a network of labor camps for “social undesirables,” including political dissidents, prostitutes, drug-users and homosexuals. Source: María Elena Solé | Letras Libres https://www.letraslibres.com/espana-mexico/politica/academias-producir-machos-en-cuba

The camps, whose brutal reality was vividly captured in Reynaldo Arena’s 1992 autobiography Before Night Falls, were part of a process of purification of people’s sexual behavior. It built on the rampant homophobia that preceded the Revolution. In pre-Castro Cuba, legislation encouraged the marginalization of homosexuals, such as the Law of Public Ostentation, a law from the 1930s that allowed the police to harass gay people for no other reason than their refusal to conceal their sexual orientation. Homosexuality was finally removed from the list of crimes enumerated in the Cuban Penal Code in 1979. It was only then that the Cuban government stopped sending homosexuals to labor camps. In 2010, in an interview with the Mexican newspaper La Jornada, Castro took responsibility for the repression of homosexuals that accompanied the Revolution, noting that “the great injustice” of the labor camps arose from the island’s history of discrimination against homosexuals, but added that “if anyone is responsible for the persecution, it’s me. I’m not going to place the blame on others.”

We can credit the continued expansion of gay marriage across Latin America to the pioneering example set by Argentina, the first Latin American country to legalize gay marriage, in July 2010, by means of a national law. Argentina was heavily influenced by developments in Spain, which in 2005 became the first overwhelmingly Roman Catholic country to enact a same-sex marriage law. But Latin America’s gay rights revolution cannot be explained away as a by-product or a reflection of gay rights progress in the developed West. We have to account for the ingenuity of local gay rights activists in marrying foreign trends to domestic opportunities. As I wrote in Out in the Periphery, Latin America’s gay rights revolution was “inspired by foreign events, but firmly grounded in local politics and realities.”

In particular, gay marriage activists in Argentina framed the struggle for gay marriage as a crusade for human rights and democratic citizenship. Beginning in the mid-1980s, and coinciding with Argentina’s transition to democracy, Argentine gay rights activists embraced the language and strategies of the human rights movement to reconstruct what once was Latin America’s largest and most influential gay rights community. Founded in 1971, Argentina’s Frente de Liberación Homosexual (FLH) brought the energy of the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion to Argentina. But the FLH met an early demise with the coming of military rule in 1976.

In 1984, with the launching of the Comunidad Homosexual Argentina (CHA), gay activists tied their wagons to the emerging Argentine human rights movement. The CHA’s founding slogan broadly suggested that its struggles went far beyond championing gay rights: “With Discrimination There’s No Democracy.” Its intention was to highlight the continuing repression of the gay community in Argentina well into the new democracy. In 1985, when the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP), a truth commission organized to chronicle the human rights atrocities of the Dirty War (1976-1983), was unable to locate anyone who had been made to disappear during the war because of their sexual orientation, gay activists memorably retorted that: “We were the disappeared among the disappeared.” In 2009, when gay activists embraced the struggle for gay marriage, they pressed the moral argument that legalizing gay marriage was in keeping with the human rights aspirations that the country had set for itself after the country’s return to democracy in 1983.

Comunidad Homosexual Argentina. Source: CHA’s Archive | https://perio.unlp.edu.ar/2020/04/01/el-comienzo-de-la-comunidad-homosexual-argentina/

None of this is to say that Latin America as a whole has charted a homogenous path in advancing gay marriage across the region. While in Argentina, Uruguay and Chile, gay marriage came through action in the national legislature, in Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica, gay activists turned their attention to the courts. In Cuba, as noted already, the issue was put to a national referendum. But almost regardless of the means by which gay marriage was secured, human rights and democratic citizenship have been front and center. A case in point is Costa Rica, the only Central American nation that allows gay marriage.

In 2016, in response to activists’ demands for gay marriage, the government of Costa Rica went to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to request that the court interpret the right to privacy and the right to equal protection under the American Convention on Human Rights. In particular, Costa Rica asked the Court to address the following issues: whether states must recognize and facilitate the name change of an individual in accordance with his or her gender identity and whether the American Convention of Human Rights requires that the states recognize all the matrimonial rights that derive from a same-sex relationship. In 2017, the Court ruled that all rights applicable to heterosexual couples should apply to same-sex couples. This forced, in 2018, the Costa Rican Constitutional Court to rule in favor of gay marriage.

As I had expected when I finished Out in the Periphery, opening the institution of gay marriage to gay and lesbian couples proved to be a boon for LGBTQ+ equality in Latin America. And, as with gay marriage, Argentina has led the way. Aside from enacting a transgender 2011 law that was a breakthrough for Latin America and indeed the world, in 2021 Argentina pioneered affirmative action for transgender people by enacting a law that mandates that one percent of all public sector jobs be reserved to the transgender community. The one percent is a symbolic figure since there are no official statistics on the number of transgender people in Argentina. In 2021 Argentina also broke another barrier by becoming the first country in Latin America (and one of the few in the entire world) to recognize “non-binary” as a third gender category in official papers, including passports. According to the decree by President Alberto Fernández, “X” will be used to denote the following meanings: “non-binary, undetermined, unspecified, undefined, not informed, self-perceived, not recorded; or another meaning with which the person who does not feel included in the masculine/feminine binary could identify.”

But two things about the trajectory of gay rights in Latin America since my book was published have truly surprised me. The first one is the absence of an U.S.-style gay marriage political backlash. To be sure, there has been a robust conservative pushback against gay rights across Latin America. Countries like the Dominican Republic, Guatemala and Paraguay have either banned or attempted to ban gay marriage in their constitutions and statutory laws in reaction to gay rights advances elsewhere in Latin America. Anti-gay violence also continues to mar Latin America’s gay rights revolution, with the region having the paradoxical distinction of being both one of the most advanced regions when it comes to legal protections for LGBTQ+ people and but also the most dangerous place in the world for being LGBTQ+.

Although anti-gay violence is a region-wide epidemic, Brazil continues to draw the lion’s share of attention. According to the Observatory of Deaths and Violence Against LGBTI+, an NGO whose data is used by Brazil’s Ministry of Human Rights and the National Secretariat for the Rights of LGBTQA+ People, in 2022 Brazil recorded 273 violent deaths of LGBTI+ individuals. Out of these deaths, 228 were classified as murders, accounting for 83.52 percent of all cases. Clearly the 2019 decision by the Federal Supreme Court of Brazil that ruled homophobia a crime has yet to have any visible impact.

But nowhere in Latin America where gay rights have actually flourished, not even in Brazil with its vociferous and politically connected Evangelical community, has any government seen fit to enact a law as ignoble as the Defense of Marriage Act, a law enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1996 that barred the federal government from recognizing same-sex marriage, even though at the time no locality anywhere in the world allowed such marriages. Nor has any major Latin American nation enacted laws that allow for the discrimination of gay people in the name of religious freedom, so-called Religious Freedom Restoration Acts.

Much the differences in the intensity of the gay marriage backlash in Latin America and the United States is rooted on how the struggle for gay rights was framed in both regions. Whereas U.S. gay activists dwelled on how gay rights would bring rights and benefits for gay and lesbian families and helped in maninstreaming homosexual lifestyles, Latin American gay activists stressed how gay rights would work to deepen democracy, citizenship and human rights. Among other things, the more ambitious and idealistic framing employed in Latin America found greater resonance with society at large; it was also a more effective rhetorical strategy for demobilizing the opposition to gay rights.

Another thing I did not foresee was how the struggle for gay marriage in Latin America would prove so fruitful for the expansion of other social rights, especially abortion. In recent years, as the United States has moved in the direction of eliminating or severely curtailing access to legalized abortion, Latin America has moved in the very opposite direction. Indeed, talks of an abortion rights revolution in Latin America are not exaggerated. In recent years, the region’s major countries have brazenly shed some of the most draconian abortion laws imaginable. Argentina paved the way in 2020, by enacting a law that allows women to abort for any reason within the first 14 weeks of pregnancy. Prior to this law, abortion was available in Latin America only in Cuba and in Uruguay. Soon thereafter Argentina’s landmark law went into effect, the high courts in Mexico and Colombia legalized abortion in 2021 and 2022, respectively. In the case of Mexico, it was left to the individual states to regulate abortion, but in Colombia it was authorized up to the 24th week of pregnancy, making the country one of the most liberal in the entire world when it comes to abortion.

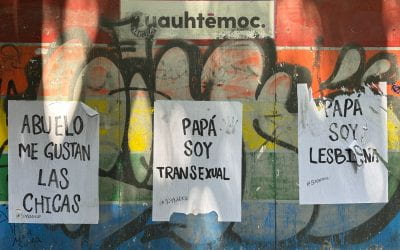

Banner in the demonstration “Day for Decriminalization of Abortion in Latin America and the Caribbean,” in Mexico City, Sept. 28, 2020. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell, ABC News, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/latin-america-womens-rights-groups-abortion-win-mexico-103018403)

In seeking to establish a right to terminate a pregnancy, abortion activists in Latin America have displayed an impressive array of strategies. Above all, perhaps, they have made the case that criminalizing abortion punishes poor women who cannot afford to have an abortion by going abroad and or availing themselves of the service of private doctors. Abortion activists also crafted a very savvy publicity campaign around the idea of the marea verde or green tide, which enlisted young women taking to the streets demanding abortion rights while waving green handkerchiefs. Less apparent is that pro-abortion activists have also displayed a lot of what they learned from the campaign for gay marriage, which is not that surprising since some of the most effective gay rights activists in Latin America have been feminist lesbians, including María Rachid, who led in the fight for gay marriage in Argentina.

One lesson that abortion activists took to from the same-sex marriage struggle is that persistence pays. After Argentine abortion activists lost an agonizing vote in the Argentine Senate in 2018, they quickly regrouped and began to mobilize women around the idea of Ni una menos (Not one less), which inspired women from Brazil to Mexico. This was a replay of what gay marriage activists did in Argentina between 2009 and 2010: they turned an initial defeat in the Congress into a launch pad for a vibrant social movement. Abortion activists also took a page from the messaging playbook of gay marriage activists, especially the framing of the right to a legal abortion as a basic human right. At least in this respect, the abortion campaign in Latin America has diverged significantly from its U.S. counterpart. For the most part, U.S. abortion activists have traditionally framed their struggle as a matter of personal, bodily autonomy.

Abortion rights in Latin America provide a window into how Latin America’s gay rights revolution is reshaping social movement politics across the region. Just as apparent, if not more, is that Latin America’s gay rights revolution is also upending our impressions of the region’s capacity to embrace social change. It’s hard to think of something that has done more to shed Latin America’s reputation as a social backwater than the progress the region has made on LGBTQ equality. That this progress often came sooner and with less backlash than in the United States enhances the extraordinary nature of Latin America’s gay rights advances.

Omar G. Encarnación is the Charles Flint Kellogg Professor of Politics at Bard College, where he teaches comparative politics and Latin American and Iberian Studies. His most recent book is The Case for Gay Reparations (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.