Museo Minca

A Love Story

The most common museum visits include seeing invaluable objects or an informational tour. What marked the difference in our museum was the ability to encounter two people with different perspectives of the same reality. On one hand, a foreigner who discovered in Minca a connection with history and a place to call home. On the other hand, a local who felt supported by the trust of those voices that found in Museo Minca a space of their own when in other times it was difficult to speak, and the knowledge that now those silenced voices could come to life.

Before the museum, people in Minca saw me and identified me [Manuel] by my family and its history in the region, but I think that with this project, little by little, I have earned the respect of my community because I have had the courage to speak and safeguard their stories with respect and responsibility. As a post-conflict region, Minca did not have a space to talk about the past during the conflict and its aftermath. As the years passed, the oldest of the population passed on from this world, and with them went their memories, their words fading into forgottenness. In the words of Gabriel Garcia Marquez: “Death comes not with age, but with oblivion.” Our mission was and is to protect those stories and transform them into “living memory.”

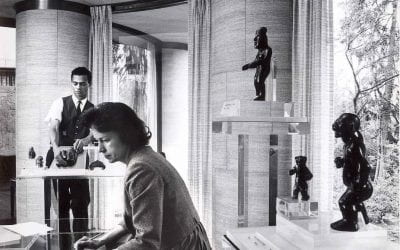

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

I [Shenandoah] don’t usually like museums. Those who know me are understandably surprised that I co-founded a museum. Those who don’t know me are also surprised. I don’t think either of us fit the image people have in mind for museum founders. But Museo Minca is not like most museums. At its core, Museo Minca is not just about preserving the past. It is about challenging us to build a better future.

When I arrived in Minca in 2016 all I wanted was an escape from my summer job in the hot, urban chaos of Barranquilla. My plan was to visit, not to stay, but for some reason, I felt I could not leave. My new friends brought me into their lives with open arms. They patiently listened to my broken Spanish, taught me how to make arepas and shared countless cups of sweet tinto (coffee). When they told me to be careful about whom I trusted, to guard my friendship, it was years before I understood that mistrust was a survival tactic. For such a small town, I was surprised how numerous and deep the divides between people were.

Minca is a complicated place and relationships are precarious. There are divisions between Colombian tourists and international tourists. Visitors from the coast and visitors from other parts of the country. Those who have moved to the area from elsewhere are subdivided into those who lived there during the conflict and those who came after the violence had subsided. Then there are families who had the resources to leave when the town was taken over by armed groups, and those who had no choice but to stay. Some families aligned themselves with one side or another for protection, and some remained as uninvolved as possible. Each group has a very different understanding of what happened, of their role in the community, and of their priorities in the post conflict renegotiation of Minca’s future.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

As a citizen and native of Minca who lived firsthand the threats and takeovers of the guerrilla, and afterwards coexisted with paramilitary groups, I grew up with doubts about knowing who was good and who was bad. I have always been interested in knowing the ‘why’ behind all the destruction, and the political history of Colombia has always interested me, but I followed the advice of my parents and family: “when they ask you ‘what to you think about the conflict?’ Don’t comment, be silent.” I did not contradict their way of thinking because they saw family and friends depart from this world at the hands of armed groups.

As a foreigner, I didn’t know any of this. In 2016, the town was just gaining fame as an international tourist destination. Each morning, I would walk to the center of town, drink a coffee and watch as shared taxis, or collectivos, were swarmed by motorcycles offering to drive passengers to luxury hostels. It’s hard not to fall in love with the natural beauty of Minca, nestled between the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Caribbean Sea, but it would have been easy to come and go, dismissing Minca as a beautiful but hollow tourist town. I only stayed out of a stubborn desire to improve my Spanish.

As my language skills grew, so did my relationships with people, which in turn cultivated an unexpected but powerful curiosity about what Minca was like before tourism. I was surprised that information about recent Colombian history—especially about the conflict—was difficult to find; information specific to Minca was nonexistent. Developing an understanding based on conversations was a lot like piecing together shards of shattered glass; they clearly fit together but figuring out how seemed impossible.

This changed when my friends introduced me to their cousin, Manuel. He patiently told me his stories and answered my questions.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

“Don’t comment, stay silent”

For a long time, I dedicated myself to listening and never commenting, but when a foreigner asked me about the history of the conflict, I saw the opportunity to get off my chest all that I had kept inside, because I thought she would just listen and leave as the months went on. I never thought that it would be the beginning of a beautiful relationship. She was excited to make known the history of the town to its visitors, but more than excitement, I felt afraid. I explained that for her it was easy to leave if the work got dangerous, but for me it was a possible ticket out of this world because it was easier to threaten and kill a Colombian than someone from the United States. For a long time, she insisted on having a space to tell these stories, so that people would get to know the Minca that did not appear in guidebooks.

The more I learned, the more frustrated I got with the types of tourism I kept encountering. Some people were blatantly disrespectful, in the country only for drugs and parties. Others were following the well-beaten backpacker trail between sights. Either way, they were blind to the realities below the surface. Even around Minca itself, there are several places that are social media wonders, photographs everyone seems to want to duplicate.

One of the most jarring pieces of information I learned was that one of these Instagram famous vistas was also a mass grave. I was horrified to find that I had been The Tourist in the Photo and felt driven to balance out my ignorance. I wanted to make sure the community of Minca knew that there were people who cared and honored their story, that our missteps were out of ignorance, not disrespect or callousness. I wanted to be a conscientious tourist; I wanted to know how to best support the community and contribute to their building of a better future.

As the years passed, Shenandoah and I focused more on our personal relationship. In 2017, we traveled to Chile and decided to visit Villa Grimaldi, a museum and memorial that shows the harsh reality of the dictatorship. I listened and walked through its walls, the story making me feel part of that history of pain and suffering which the Chileans lived through. At the end of the tour, I looked at Shenandoah and told her that Minca also needed to be heard.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

When Manuel and I set about designing the physical space for Museo Minca, we reflected on which spaces had impacted us and why. Memorial museums like Villa Grimaldi in Chile and the Museum of the Civil War in Nicaragua both exemplified the highly personal, reflective experiences we wanted to channel. Our major conclusion was that we needed a personal space that would bring people face to face with others’ realities—identities across space, time, location—whose lives may have been very different from our own.

How do we question truth, history, hierarchies of narrative and who has the right to tell what story? How do we leave people thinking?

The importance of plurality of stories and perspectives, the way they connect us and help us to understand ourselves and each other, was one of the biggest lessons we learned as Casa de la Memoria – Museo Minca took shape.

When we arrived back home, we began looking for an appropriate way to tell these stories and incorporate a complete history of the Sierra, not only focused on conflict but also its beautiful and interesting past with indigenous groups and the start of coffee farms in the region. It was tedious at first trying to gain trust and convince townspeople to tell these stories because before us there had been many university “projects” regionally and locally that wanted to study what the community of Minca had lived through, but the story remained forgotten, and there had never been a commitment to real change. For the townspeople of they were just passing projects that extracted information that only served the student and their grade, or some scattered applause.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

We got lucky. As an outsider, there are many things that I am incapable of understanding. As we began to interview people more formally, it became clear that some individuals only felt comfortable sharing their stories because of the trust they had in Manuel, who was one of their own. Because he lived through the same dangers, they felt comfortable that he would handle their story with discretion and protect them. He knew the dangers. However, there were other people who were more comfortable speaking to me because I was a blank slate, because they knew that I had no connection to either side of the conflict personally. It was only between the two of us that we could gather the stories we did. Moreover, it was only because building Museo Minca and its narrative was an inherently collaborative community process that the information meant anything at all.

When we succeeded in convincing people to relate their experiences, it was difficult not to be moved by their emotions. We cautiously laughed and fought back tears at the sadness of their words. Little by little, we build a narrative of memories and could appreciate the common power of stories, after which many residents sought us out, wanting to be part of the museum story.

We asked and asked, listened and listened. At first, I just wanted to understand. But the stories took on a life of their own. These little shards of truth helped to imagine a history that is dynamic, nuanced and inclusive. Because the truth is, by nature, complex. Post-conflict life is complex. Understanding and reconfiguring the identity of a town is complex. Another side of that complexity is that conflict and violence don’t exist in a vacuum. Atrocities coexisted with joy, bonanza, resilience, and hope. Some people we interview don’t speak about the conflict at all, they tell us instead about how their families arrived in the area, what it was like to grow up on a coffee farm or their favorite town festivities.

Museo Minca opened its doors to give the local community a place to house and honor the stories the community wants to share. It is a place where visitors can come to engage directly with the local community, their lived experiences, and the complex realities they face.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

When we officially inaugurated Museo Minca, we invited the entire community: newcomers, elderly, foreign residents of Minca, and in that moment we felt harmony amongst them. We shared drinks, food and experiences; we felt pride when we saw in their faces trust and belief in the project, that the voice of the silenced now had a space where it would be heard and respected.

We started with a table, two chairs, a coffee machine, some old photographs and stories.

By 2020, Museo Minca had three rooms, a full team and was the number one destination on TripAdvisor. We had led countless community workshops, connected travelers from more than 40 countries to local entrepreneurs, worked with the government to promote sustainable tourism and funded numerous community-led development projects. This success was entirely due to the participation and faith from the community of Minca, and the impact their stories had on visitors from all over the world.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

Our museum is simple. When you walk inside, you see walls lined with old photographs. You have the option to wander on your own or allow a host to guide you through a highly personal, interactive narrative experience that contextualizes the local history. At the end, you can sit with our archive of first-person testimonies. When you are ready, we offer you tinto, and sit down to talk and answer any questions you might have, just as Manuel and his family did for me when I first arrived. And I dare you not to fall in love with Minca and its people even more deeply.

Sadly, Museo Minca shut its doors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our team is developing virtual content, continuing to work the community of Minca. We are anxious to open our doors to the public once again.

Museo Minca

Una Historia de Amor

Por Manuel Balaguera y Shenandoah Cornish

Lo más común de visitar algunos museos es encontrarse con objetos invaluables o con un guion muy pocas veces cambiante, lo que marcó la diferencia en nuestro museo era poder encontrar a dos personas con diferentes perspectivas de una misma realidad. Por un lado, una extranjera que descubrió en Minca una conexión con su historia y un lugar al que pudo llamar hogar y en la otra parte un lugareño que se sintió respaldado con aquellas voces de confianza que encontraron en el Museo Minca un espacio propicio en donde tiempos anteriores era difícil hablar de esos temas, pero que ahora esas voces del silencio cobrarían vida.

Antes del proyecto Museo, las personas en Minca me [Manuel] veían y me identificaban por mi familia y su antigüedad en el en la región, pero considero que con este proyecto me ganado poco a poco el respeto de mi comunidad porque he tenido el valor de hablar y salvaguardar las historias con respeto y responsabilidad, siendo Minca una zona posconflicto no contaba con un espacio en donde se hablara de lo quera antes, durante y después de las secuelas del conflicto. Con el paso de los años su población más longeva iba partiendo de este mundo y junto a ellos se iban sus memorias y sus palabras quedaban en el olvido, en palabras de Gabriel García Márquez; “la muerte no llega con la vejez si no con el olvido” nuestra misión era y será rescatar esos relatos y transformarlos una “memoria viva”.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

Normalmente no me [Shenandoah] gustan los museos. Los quienes me conocen se sorprendan que ayude a fundar un museo. Los quienes no me conocen también se sorprendan. No creo que ningún de los dos pegamos con el imagen mental de fundadores de museos. Pero Museo Minca no es un museo normal. La esencia de Museo Minca no es la preservación del pasado, pero mas bien un reto de construir un futuro mejor.

Cuando llegue en Minca en 2016, solo buscaba un escape de mi trabajo en el calor y chaos urbano de Barranquilla. Mi plan era visitar, no quedarme, pero por algún razón no sentí capaz de irme. Nuevos amigos me abrieron sus brazos y puertas. Escuchaba mi pésima español con paciencia, me enseñaron a hacer arepas y compartíamos vasos de tinto innumerables. Cuando me advirtieron de tener cuidado con mi confianza, de guardar mi amistad, dure años sin entender que esta desconfianza era una táctica de sobrevivencia. Por un pueblo tan pequeño, me sorprendió multitud y profundidad de las divisiones entre personas.

Minca es un sitio complicado y sus relaciones son precarios. Hay divisiones entre turistas Colombianos e internacionales, entre visitantes de la Costa y visitantes del interior. Los que llegaron de otros sitios están subdivididos entre los que vivían allí durante el conflicto y los que llegaron después de que se disminuido la violencia. Después hay familias las cuales tuvieron los recursos de huir cuando los grupos armados se tomaron el pueblo, y los que no tuvieron mas opción que quedarse. Unas familias se alinearon con un lado u otro por protección, y otros permanecían lo mas neutral posible bajo las circunstancias. Cada grupo tiene un entendimiento distinto de lo que paso, su papel en la comunidad, y sus prioridades en la renegociación posconflicto del futuro de Minca.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

Como poblador y oriundo de Minca al vivir de primera mano la toma y hostigamiento guerrillero y posterior a eso convivir con grupos paramilitares siempre crecí con dudas de saber quiénes eran los bueno y malos, estuve interesado de saber el porqué de tanto daño siempre me intereso la historia política de Colombia, pero seguía el consejo de mis padres y mis familiares “cuando le pregunten ¿qué piensa usted sobre el conflicto? No opine quédese callado” y no contradecía su forma de pensar porque ellos vieron familiares y amigos partir de este mundo en manos de grupos armados.

Como extranjera, no sabia nada de esto. En 2016 el pueblo apenas estaba ganando fama internacional como destino turístico. Cada mañana, caminaba hacia la plaza para tomar un café y ver llegar colectivos rodeados por mototaxis ofreciendo sus servicios para llevar pasajeros a hostales lujosas. No es difícil enamorarse de la belleza natural de Minca, entre la Sierra Nevada y mar Caribe, pero hubiese sido fácil llegar y partir, desestimando Minca como un hermoso pero hueco pueblo turístico. La única razón lógica para quedarme era mi terca deseo de mejorar mi español.

Junto con mi vocabulario crecía mis relaciones con personas del pueblo, lo que a su vez siembro un inesperada pero poderosa curiosidad sobre como era Minca antes de la llegada del turismo. Me sorprendió que información sobre historia moderna de Colombia—especialmente sobre el conflicto—era muy difícil encontrar; información sobre Minca específicamente era inexistente. El desarrollo de un entendimiento a base de mis conversaciones era como pegar pedazos de vidrio partido; seguramente encajaban pero encontrando la forma sentía imposible.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

“No opine quédese callado.”

Por un largo tiempo solo me dedique a escuchar y nunca opinar, pero cuando una extranjera me preguntó sobre la historia del conflicto pues vi la oportunidad de desahogarme de todo lo que tenía en mi mente porque pensé que ella solo escucharía y partiría con el paso de los meses, pero jamás pensé que eso era el principio de una linda relación, ella muy emocionada de dar a conocer a los visitantes al corregimiento de esta historia, pero yo más que emoción sentía miedo y le explicaba que para ella era fácil partir en caso de una represaría pero para mí era un posible boleto de partida de este mundo ya que era más fácil amenazar y matar a un colombiano en comparación con un estadounidense, por un largo tiempo ella insistió en tener un espacio para contar esa historias y que la gente conociera a esa Minca que no aparecían en los libros de guía turística.

Lo más que aprendí, lo mas frustrada que me sentí con los tipos de turismo que encontraba. Unas personas descaradamente faltaban respecto, solo estando en el país por drogas y fiestas. Otros seguían el bien transitado camino mochilero entre destinos turísticos. Ambos eran ciegos a la realidades bajo el superficie. Alrededor de Minca mismo hay varios sitios famosos por redes sociales, fotografía que al parecer todos quieren duplicar.

Uno de lo más chirriante pedazos de información que aprendí era que uno de estas vistas famosas por Instagram era una fosa común. Quede horrorizada al enterarme que yo también había sido ‘La Turista en La Foto’ y me sentí impulsada retribuir mi ignorancia. Quería asegurar que la comunidad de Minca sabía que hay personas que les importa y honoran su historia, que nuestros traspiés eran por ignorancia no falta de respecto o callosos. Quería convertirme en un visitante consciente y saber la mejor forma de apoyar la comunidad, y contribuir a su creación de un futuro mejor.

Con el paso de los años, enfoquemos mas que todo en nuestra relación personal. Viajamos a Chile en 2017 y decidimos visitar Villa Grimaldi, una casa museo que muestra la dura realidad de la época de la dictadura, escuché y camine a través de sus paredes y con la narrativa me sentía adentrándome a historia de dolor y sufrimiento por el que pasaron los chilenos al finalizar el recorrido mire a Shenandoah y dije Minca también necesita ser escuchada.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

Cuando Manuel y yo empecemos a diseñar un espacio físico para Museo Minca, reflejemos sobre los espacios que a nosotros nos habían impactadas y porque. Museos de memoria como Villa Grimaldi en Chile y el Museo de la Guerra Civil en Nicaragua los dos ejemplificaban la experiencia personal a reflectante que queríamos capturar. Nuestra conclusión principal era la necesidad de un espacio donde personas se enfrentaran las realidades de otros—transciendo espacio, tiempo y ubicación—y cuyos vidas podrían ser muy diferentes.

Como cuestionamos verdad, historia, jerarquías de narrativas y quienes tienen el derecho contar cuales historias? Como podemos dejar personas pensando?

La importancia de pluralidad de historias y perspectivas, la forma que nos vinculan y nos ayudan a entender nuestros mismos y los demás, era uno de las lecciones mas grandes que íbamos aprendiendo mientras de que Casa de la Memoria – Museo Minca se formó.

Cuando llegamos al pueblo nos colamos la tarea de buscar una forma apropiado para contaríamos esas narrativas y como darle un toque completo de historia de la Sierra no solo enfocada en conflicto sino también de su lindo e interesante pasado a manos de grupos Indígenas y del comienzo de las plantaciones de café en la región, fue tedioso al principio tratar de ganar confianza y convencer a los pobladores de contar esas historias puesto que anterior a nosotros habían muchos “proyectos” universitarios locales y regionales que se interesaron por estudiar lo que los pobladores Miqueros vivieron, pero se quedaba en el olvido no había un compromiso de transformación verdadera para los pobladores solo eran “proyectos” de paso que acogían los relatos y les serviría únicamente al estudiante para una buena nota y unos cuantos aplausos.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

Tuvimos suerte. Como forastera, hay muchas cosas que no soy capaz de entender. Cuando empecemos a entrevistar mas formalmente, era muy clara de que unas personas solo sentían cómodos compartiendo sus historias por la confianza que tuvieron en Manuel, quien es de los suyos. Porque había vivido los mismo peligros, confiaban de que el tendrá discreción y cuidado con sus relatos y seguridad. Conocía el peligro en hablar. Pero al otro mano, habían personas mas cómodos hablando conmigo porque me vieron como una tabla en blanco. Sabían que yo no tenia ningún vinculo personal con ningún lado del conflicto. Solo era entre los dos que pudimos recolectar las historias. Mas, era porque la construcción de Museo Minca y su narrativa era un proceso inherentemente colaborativo y comunitario que la información tuvo algo de significado.

Cuando logramos convencer a las personas para contar sus vivencias sentimos que no fue fácil dejase contagiar de sus emociones reíamos con cautela y nos aguantamos las ganas de llorar bajo la tristeza de sus palabras. Poco a poco fuimos construyendo memoria y pudimos apreciar el poder común de la palabra, ya después muchos pobladores querían ser parte de esa narrativa museal.

Preguntábamos y preguntábamos, escuchábamos y escuchábamos. Del principio, solo quería entender. Pero las historias cobraron vida solas. Esas pequeñas pedazos de verdad ayudo a imaginar una historia dinámica, matizada y inclusiva. Porque la verdad es, por su naturaleza, compleja. El posconflicto es complejo. Comprender y reconfigurar la identidad de un pueblo es complejo. Más, la violencia no se da en un vacío: atrocidades coexisten con alegría, bonanza, resiliencia y esperanza. Unas entrevistados ni hablan del conflicto, en cambio cuentan sobre como sus familias llegaron a la zona, como era crecer bajo matas de café, o sus festividades preferidos del pueblo.

Museo Minca abrió sus puertas para dar a la comunidad local un sitio para albergar y honrar sus historias. Es un lugar donde visitantes pueden interactuar directamente con los lugareños, sus experiencias, y los realidades complicados que enfrentan.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

Cuando oficialmente inauguramos el Museo Minca invitamos a toda la comunidad; nuevos, viejos y extranjeros habitantes de Minca, en ese momento sentimos una armonía en los pobladores, compartieron bebidas, comidas y experiencia, sentimos un gran logro al ver en sus rostros confianza en el proyecto y sentir que esa voz del silencio contaría con un espacio donde podría ser escuchada y respetada.

Empecemos con una mesa, dos sillas, una maquina de café, unas fotografías viejas y relatos.

En 2020 Museo Minca contaba con tres cuartos, un equipo de trabajo, y logro ocupar el primer puesto en recomendaciones de TripAdvisor. Facilitemos numerosos talleres comunitarios, conectado visitantes de mas que 40 países a emprendedores locales, trabajemos con el gobierno local y nacional para promover turismo sostenible, y financiado varios proyectos de desarrollo comunitario dirigidos por la comunidad misma. Este éxito era totalmente debido a la participación y confianza de la comunidad de Minca, y el impacto que tuvo sus relatos a visitantes internacionales.

Photo courtesy of Shenandoah Cornish.

Nuestro museo es sencillo. Cuando entras, ves paredes forrados con fotografía vieja. Tienes la opción de explorar solo o ser acompañado por un anfitrión quien te guía por una experiencia narrativa personalizada e interactiva que contextualiza la historia local. Al final puedes sentar con nuestro archivo de testimonios en primer persona. Cuando estés listo, te brindamos un tinto para sentarnos, hablar y contestar cualquier pregunta que puedas tener, igual que Manual y su familia me hicieron a mi cuando llegue. Y te reto no enamorarte de Minca y su pueblo mas profundamente.

Tristemente, Museo Minca cerró sus puertas durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Nuestro equipo esta desarrollando contenido virtual y sigue trabajando a mano con la comunidad de Minca. Estamos ansiosos poder abrir nuestras puertas al público nuevamente.

Manuel Balaguera was born and raised in Minca, Colombia. He worked as an educator for displaced and at-risk youth in the Santa Marta area. This past year he relocated temporarily to the United States and teaches Spanish as a second language.

Shenandoah Cornish is currently pursuing a master’s degree at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. Her focus is on cultural diplomacy, hierarchies of narrative, and identity in transitional justice; in many ways inspired by and based on lessons from Manuel, her personal and professional partner.

Learn more at www.museominca.org or museominca@gmail.com.

Manuel Balaguera nació y creció en Minca, Colombia y pertenece a dos de las familias mas viejas de la zona. Trabajaba como profesor para jóvenes desplazados y de alto riesgo alrededor de Santa Marta. El ultimo año se reubicó a los Estados Unidos temporalmente y enseña español como segunda idioma.

Shenandoah Cornish está completando su maestría en el Fletcher School of Ley y Diplomacia en la Universidad de Tufts. Su enfoque es diplomacia cultural, jerarquías de narrativos, e identidad en justicia transicional inspirado mas que todo por lecciones de Manuel, su pareja personal y profesional.

Aprende mas en www.museominca.org o escribanos a museominca@gmail.com.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.