Remaking the Welfare State

Pandemic Successes and Failures in Chile

Covid-19 has exposed the best and worst of countries. Indeed, the pandemic has laid bare, often times in painful detail, the strengths and weaknesses of our societies, leaders, economic systems and political institutions. Nowhere do we see this more acutely than in Latin America, a region ravaged by the virus.

I study social policy and politics in Latin America, and much of my work focuses on Chile. The Covid-19 crisis has exposed with great clarity the achievements and shortcomings of Chile’s social protection system. On the one hand, there are reasons to applaud. The pandemic has revealed the strong capacity of Chile’s state and extensive public health system. The country has a relatively high rate of testing and a remarkable vaccination program. On the other hand, unequal patterns of illness and death, persistent social vulnerability and gaps in healthcare quality shine a light on deep inequalities built into Chile’s public health system and welfare state.

Following the 1990 return to democracy, Chile witnessed a steady increase in spending on social programs, including education and healthcare. Beginning in the early 2000s, the center-left governments of presidents Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet oversaw a series of policy reforms that expanded access to public services and income support programs, moving health, social assistance and, to a lesser degree, education, in a more universalistic direction.

These reforms were important, but they failed to break with the underlying neoliberal logic of Chile’s welfare system; a logic put in place during Augusto Pinochet’s 17-year dictatorship. As a result, the policy initiatives of the early 2000s improved access, but often provided insufficiently sized benefits or failed to address problems of the quality of public services. All of this contributed to the maintenance of inequality between various sectors of Chilean society: formal and informal sector workers; women and men; indigenous and non-indigenous; rich and poor; and residents of different regions and municipalities.

Chile identified its first confirmed case of Covid-19 on March 3 and registered its first death on March 21. The government of center-right president Sebastián Piñera was slower and less comprehensive than its neighbors in ordering lockdowns. Chile closed its borders and declared a state of emergency in mid-March, invoking a curfew on March 22 and a partial lockdown of the Metropolitan Region—the area surrounding Santiago— shortly thereafter.

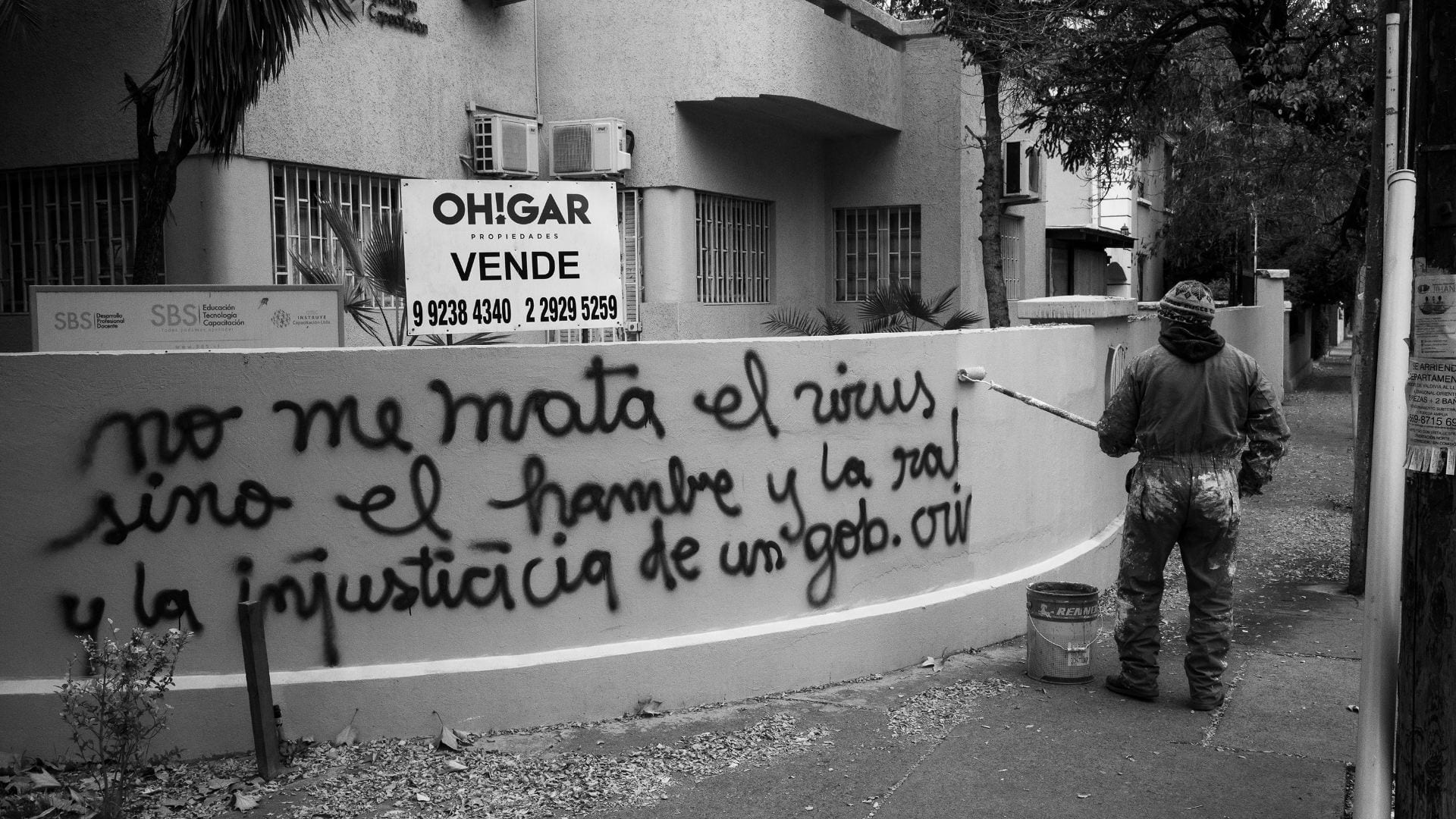

Cleaning up graffiti on Avenida Pedro de Valdivia in Santiago de Chile. Photo by Luis Weinstein, who received an honorary mention in the digital exhibition, Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 through Photography, co-sponsored by ReVista and the DRCLAS Art, Film and Culture Program.

After initial success in slowing the spread of the virus, Chile began to reopen in May, but cases quickly surged, pushing authorities to re-impose lockdowns in the Metropolitan Region and other parts of the territory. Onlookers noted that the soaring cases—some of the highest rates in the world—were deeply troubling, but also reflected the Chilean state’s capacity to offer testing.

In April 2020, when much of Latin America was unable to diagnose cases due to test scarcity, Chile was already conducting roughly 2,900 tests per one million residents—the highest rate in the region. More recent data shows that the country has continued to lead Latin America, along with Uruguay, conducting between 3-3.5 tests per 1,000 people. While low compared to Europe, this rate is much higher than Argentina, which records just under one test per 1,000 or Mexico, which conducts 0.12 tests per 1,000 people.

While strong state capacity and a public health system with near-universal coverage and broad territorial reach helped Chile with testing, gaps in the quality of public health services and deep socio-economic inequalities have meant that the effect of the virus varied across social groups. Like in so many countries, Covid-19 in Chile has taken the heaviest toll on marginalized sectors, underscoring deep inequalities that have yet to be addressed by social policy reforms.

A study of the Santiago Metropolitan Region revealed that during the winter case surge, infections in high-income municipalities grew from around 10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants to 32 cases per 100,000 people. In poor municipalities, by contrast, cases grew from roughly 10 per 100,000 people to a peak of 68 per 100,000.

The death rate was also higher in low-income municipalities during the winter surge, reaching 188.6. In wealthy municipalities, the Covid-19 mortality rate during the surge was half of that at 90.9. This difference can be partially understood by a June report that found the Covid-19 mortality rate in Santiago’s public hospitals was twice that of private clinics. All of this points to persistent weaknesses in Chile’s public healthcare system—gaps that were not fully addressed by the social policy reforms undertaken by presidents Lagos, Bachelet, and Piñera.

Higher rates of infection and death among poor Chileans also point to a series of other inequalities that the country’s welfare state has yet to address, including differences in access to quality employment, income support programs, and housing. Around 29.5 percent of Chilean workers operate in the informal sector, working at jobs that are unregulated and often times low-paying. While this number is low compared to most other countries in the region, it means that at least one-third of Chilean workers are highly vulnerable.

Informal-sector workers were especially hard hit by the pandemic because they are not protected by unemployment insurance and other contributory income protection programs. Moreover, these individuals often rely on their day-to-day earnings to get by. During the pandemic, these workers were forced to make an impossible choice: stay home and risk poverty or return to work and risk infection. This dilemma points to lingering weaknesses in Chile’s social protection system, namely the insufficiency of social assistance and limited access to quality employment.

Since the 1990 return to democracy, Chile has made impressive progress in reducing poverty. Between 2006 and 2017, the share of the population living in poverty fell from 16.5 to 6.3 percent. Despite this progress, social vulnerability has remained high. A 2017 study of multidimensional poverty showed that 30.7 percent of Chileans were deficient in social security protection. Moreover, the share of those who had trouble in getting work, pensions, basic services to the home, housing and security increased between 2015 and 2017, indicating that vulnerability was on the rise as Chile headed into the pandemic. This hardship has worsened during the past year and recent studies show that the number of squatter settlements in Chile grew by 20.8 percent in 2020, while ollas communes to feed the hungry also proliferated.

Covid-19 made clear how these vulnerabilities open individuals and households to risk, increasing the likelihood of falling back into poverty or facing illness and early death. In March 2020, the Piñera administration responded to growing hardship and job losses, investing in unemployment insurance, increasing family allowance benefits, and creating a new cash transfer for uncovered individuals—the Emergency Family Income (IFE). In March, the president announced additional spending measures.

Recent data released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows that Chile invested more than almost any other Latin American state in economic and social relief to address the crisis. In research with Merike Blofield and Cecilia Giambruno, we find that Chile is second only to Brazil when it comes to the breadth and sufficiency of its cash transfer response to Covid-19. These policies are important, but have so far been unable to compensate for lingering weaknesses in Chile’s welfare state.

Chile’s response to the pandemic also revealed a central tension in the country’s political arena, namely the growing gap between elites and the public. As cases surged in May 2020, then-Health Minister Jaime Mañalich noted that enforcing lockdowns had proven difficult because high levels of vulnerability meant that many Chileans could not afford to stay home. Mañalich added that, until that point, he had been unaware of the severity of poverty and overcrowding that are characteristic of many Santiago neighborhoods.

The Minister’s revelation captured the dynamics that inspired Chile’s October 2019 mass protests: an immense gap between the lived experiences of the governed and those who govern. This disconnect, in turn, has fueled discontent with the political elite, political parties and democratic institutions more broadly.

One area where the pandemic has underscored a strength in Chile’s social protection system is in the Covid-19 vaccination program. Chile began its vaccination campaign in late December and by mid-March the country led the world in the number of shots per 100,000 people. As of April 6, Chile had delivered a first dose of the Covid-19 vaccine to 37.5 percent of the population and two doses to 22.1 percent.

The speed and effectiveness of the program, which has attracted world attention, points to important Chilean strengths: high levels of state capacity and a public health system with expansive coverage and broad territorial reach.

But even in Chile’s vaccine campaign, inequality persists. Government data on vaccine coverage shows that access varies across regions and municipalities. In Santiago’s Metropolitan Region, rates of coverage are lower in poor municipalities like La Pintana (30.9 percent) and Puente Alto (31.2 percent) than in the wealthier municipalities of Las Condes (58.7 percent) or Vitacura (85.2 percent).

Many reasons account for these gaps, but differences in local-level health administrative capacity and lingering socio-economic inequalities have likely complicated vaccine delivery in low-income municipalities. These differences reflect the story of Chile’s social policy development: expansion in access, but inside a system that has maintained and even reproduced long-lasting inequalities.

Growing hardship and gaping differences in how the pandemic has influenced high, middle and low-income sectors, women and men, and young and old is likely to further politicize inequality in Chile, intensifying demands for redistribution. All of this unfolds in a context of profound political transformation. On May 15 and 16, Chilean voters will head to the polls to elect a constitutional convention that is charged with writing a new magna carta. The process is sure to be marked by the demands and frustrations that provoked the October 2019 mass protests, but also by the experience of the pandemic.

Covid-19 has made abundantly clear that the state has an essential role to play in safe-guarding citizens through the provision of income support and high-quality public services. In the case of Chile, it has also made clear that a great deal of progress must be made if the country hopes to achieve such protection. All of this points to the possibility that Chile’s constitutional process will take up the issue of social rights, perhaps opening, at long last, a window for addressing the country’s lingering inequalities.

Jennifer Pribble is Associate Professor of Political Science and Coordinator of Global Studies at the University of Richmond. She is the author of Welfare and Party Politics in Latin America (Cambridge University Press). Jenny has published several peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters that analyze social policy, political parties, and inequality in Latin America, as well as public-facing work that has appeared in outlets such as the Washington Post, Financial Times, and Americas Quarterly. @PribbleJenny

Related Articles

Brazil’s Vaccinated Democracy

In March 2021, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a current presidential candidate, posed a pointed question in a speech lambasting President Jair Bolsonaro’s Covid-19 response. “Where is our beloved Zé Gotinha?” Zé Gotinha is not a respected public health expert or crisis manager

Broken Land: Climate Change and Migration in Guatemala

Broken LandClimate Change and Migration in Guatemala Santos Istazuy Pérez (right) sits in meditation during a group hike and workshop at a lush farm along with fellow Guatemalans and like-minded people from around the world including Germany and Uruguay. Photo by...

The Gift of Art

My dear friend, Colombian pioneer performance artist, Maria Evelia Marmolejo, (Cali, Colombia, 1958) whom I met during the research for the exhibition Radical Women: Latin…