Seeking Rights from the Left

Latin American LGBTQ+ Politics

Nearly a decade ago, I attended a regional academic conference in Medellín, Colombia, to present on an eight-country study I was coordinating, which asked: do Left governments help to achieve women’s and LGBTQ+ people’s rights? Exploring a long-held assumption, an interdisciplinary group of researchers from across the Americas were focusing on the “Pink Tide” (2000-2015), studying whether governments which sought to eliminate inequality included gender- and sexuality-based movements and demands.

I walked out of the conference hall one evening with collaborators hailing from Canada to Argentina to the sight of hundreds of people gathered in a candlelight vigil. We drew close, eager to understand their plight. “Con mis hijos no te metas!” read the slogans on their baby blue and pink banners: don’t mess with my kids! A middle-aged woman thrust pamphlets at us explaining their demand: to stop the promotion of “gender ideology” through sex education programs. They claimed that teaching children gender is a social construct, that people should have control over their bodies, and that LGBTQ+ people are deserving of dignity, was a frontal attack the family and could convert boys and girls to homosexuality. As my dispirited colleagues explained to me, a movement was growing across Latin America to insist that gender and sexual rights had no place in schools— nor in academic research.

Marcha por La Vida, Peru, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marcha_Con_mis_hijos_no_te_metas_%289%29.jpg

Our experience on the streets of Medellín brought home the complexity of gender and sexuality politics from our project. At the height of the Pink Tide, some left-leaning governments were at the forefront of an explosion of rights and recognition: passing anti-discrimination legislation; legalizing same-sex unions and marriage; enabling same-sex couples to adopt; and responding to transpeople’s demands for gender identity recognition and social equity. In reaction, increasingly organized right-wing movements, often religiously inspired (and frequently U.S.-backed), objected that the state had gone too far and was damaging society. And in an ironic twist, the countries that leaned most heavily towards leftist transformation often excluded or watered down feminist and LGBTQ+ demands. Project participants speculated that, seen through gender and sexuality lenses, the right-left ideological spectrum itself should be recalibrated.

As we argued in the collection Seeking Rights from the Left: Gender, Sexuality, and the Latin American Pink Tide (Duke University Press 2019; published in Spanish as Género, sexualidad e izquierdas latinoamericanas: el reclamo de derechos durante la marea rosa. CLACSO, 2020), two reasons for our general observations stood out. First, where radical political leaders struck deals with conservative religious ones to get the Catholic or Evangelical vote, they would coopt, sideline or even attack the those “seeking rights from the Left.” Second, equity and inclusion depended on democratic structures and practices – civil rights, judicial independence, legislative debate, fair elections. Where populist, if not authoritarian, presidents and their followers eroded democracy, gender and sexuality rights were in peril.

Given that many Latin American governments are still left-leaning, what do the Pink Tide conclusions look like compared to more recent developments? As the brief review below illustrates, our central findings still hold: where democracy has come under attack, LGBTQ+ rights and communities are threatened. Other governments continue to advance rights and inclusion, even as violence, particularly directed at transwomen, inequality and right-wing objections in and outside of the state continue to grow.

Although ostensibly on the left, President Daniel Ortega has transformed Nicaragua into an authoritarian regime, dismantling constitutional checks on presidential power, imprisoning and exiling his critics, and stripping hundreds of their citizenship. He has also effectively criminalized rights movements. Under the guise of fighting imperialism, a 2020 law forces organizations or individuals who receive foreign funding, such as many activists working for LGBTQ+ rights, to register as “foreign agents.” They are branded as terrorists and traitors, and prohibited from public service. LGBTQ+ activists have been forced into exile in Costa Rica and elsewhere.

In Venezuela, where socialist President Nicolas Maduro’s ongoing efforts to exert control by persecuting his opposition while embedding the military ever further into government functions, have contributed to a multifaceted humanitarian crisis and mass exodus. LGBTQ+ rights have stalled under this regime, except for the March 2023 Supreme Judicial Tribunal’s ruling that penalizing homosexual conduct in the military is unconstitutional. The same month, however, the National Police Force raided a gay club, arresting patrons and releasing their information to the media. In just six months in 2022, nearly 100 cases of violence against LGBTQ+ people, including ten deaths, were documented; a recent survey in the community finds nearly half have experienced abuse at the hands of state security, co-workers, acquaintances or family members.

State protection and inclusion of LGBTQ+ people in Brazil have improved dramatically with the 2022 re-election of now three-term President Luis Ignacio “Lula” da Silva of the Workers’ Party. For example, efforts to ban “gender ideology” across the educational system had garnered former extreme right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro’s overt support, including through his Minister of Women. But in 2020, the Supreme Court struck down eight such laws. Moreover, responding to a case brought by the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, “Travesti,” Transgender, and Intersex Association (ABGLT), the 28-year-old national LGBTQ+ organization, the Court built on a 2019 decision recognizing homophobia as a crime with its 2023 decision that homophobic slurs can be punished with imprisonment. Significantly for a country where entrenched racism has become hotly contested, the 9-1 decision makes homophobic hate speech the legal equivalent of racist hate speech. Lula’s administration has also designated a National Secretary for LGBTQIA+ Rights.

Secretary Symmy Larrat has her work cut out for her. Brazil is the most deadly country for transpeople, according to research undertaken by Transgender Europe: in the last 15 years, more than 1,700 have been murdered. The yearly report issued by the National Association of Travestis and Transsexuals revealed that in 2022, 228 LGBTQ+ people were killed. Among the dead were 131 transwomen, with the youngest victim just 15 years old. Another 20 transwomen committed suicide. LGBTQ+ protections extend unevenly across the huge country, with 70 percent of Brazilian states having no official programs in place for the community, and only 52 percent allowing transpeople to be identified by their own names. Persistent racism exacerbates the risks of discrimination and violence. However, advocates continue to step forward: Erica Malunguinho, a Black transwoman, is now serving a second term after becoming the first trans state assembly member in the country.

In Chile, conservative President Sebastian Piñera (2018-2022), a billionaire businessman, oversaw the final approval of two critical pieces of legislation advanced under his socialist predecessor, Michelle Bachelet. In 2019, the Gender Identity Law enabled transpeople older than 14 to officially change their names and gender identity. Piñera also signed off on a progressive marriage equality law, a long-postponed demand by LGBTQ+ rights groups, in December 2022. Alongside same-sex marriage recognition, it guarantees the right to adopt and access to assisted reproduction, and no longer forces transpeople to divorce after transition. With the 2022 election of leftist Gabriel Boric to the presidency, Chile has seen the further development of LGBTQ+ access to the state through a new LGBTIQA+ consultative council including representatives of state agencies, civic organizations and activists.

LGBTQ+ rights have also been at stake in Chile’s constitutional reform process. Headed by a gay doctor, the 2021-2 Constituent Assembly developed a new constitution that centered indigenous rights and deconcentrated power in the Executive. It also enshrined gender and sexual rights in Article 61: “Every person is entitled to sexual and reproductive rights. These include, among others, the right to decide freely, autonomously and in an informed manner about one’s own body, about the exercise of sexuality, reproduction, pleasure and contraception.” After the rejection of the new constitution in a September 2022 plebiscite, advocates are concerned that a powerful far-right political coalition, linked to Catholic and Evangelical churches, will dominate the new constitutional convention, endangering LGBTQ+ rights.

Argentina continues to be a regional rights leader, well-known for its pathbreaking legalization on same-sex marriage and gender identity recognition. In 2021, it became one of the first countries in the world to enable citizens to formally identify with a non-binary gender category, “X,” on state documents, under a decree by left-leaning President Alberto Fernández. According to Human Rights Watch, the “X” officially stands for “non-binary, undetermined, unspecified, undefined, not informed, self-perceived, not recorded; or another meaning with which the person who does not feel included in the masculine/feminine binary could identify.”

President Alberto Fernández, staff and non-binary individuals standing in an “X” shape at the Casa Rosada, celebrating the decree to include the non-binary gender category “X” in official state documents. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dni_no_binario_Argentina.jpg

However, in a continuing theme traversing this diverse and unequal region, policy implementation across Argentina’s 23 provinces varies. Fernanda Rotondo, the Gender and Human Rights Coordinator for Lawyers in Human Rights and Social Studies in the Argentine Northeast, explained that in some of the poorest Northeastern provinces, “Trans women…continue to be the target of corrective violence [and] transfemicide […] They also live in contexts of structural violence where their access to work, education and housing is affected and where they also suffer […] criminalization and police persecution.”

Moreover, the populist Right is consolidating its power by catalyzing people’s unhappiness with levels of economic instability that have led to inflation rates of well over 100 percent and 40 percent of the population living in poverty. The current presidential front-runner, Javier Milei, is drawing on the ideas of what the Association for Women in Development has identified as the “anti-rights” Right, threatening to shut down the Education Ministry for “indoctrination,” including through sex education, and to close the Ministry of Women, Genders and Diversity for its promotion of “cultural Marxism,” insisting that “equality before the law” is the only equal treatment necessary.

Uruguay now ranks as the sixth most protective country of LGBTQ+ rights in the world, according to the Franklin and Marshall Global Barometer of Gay Rights. Opinion polls reveal almost half of Uruguayans strongly agree that queer politicians are acceptable, and that LGBTQ+ individuals should have the right to marry. In September 2023, More than 150,000 people turned out for 30th Diversity (formerly Pride) March; it is called the “Diversity” march because, as professor and researcher Diego Sempol attests, “ the problems of discrimination are intersectional…whether due to sexual orientation, gender, ethnic origin, social class.” Uruguay’s inclusive context has resulted in the migration of LGBTQ+ people from other countries, including Brazil during Bolsonaro’s administration, Cuba, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic.

Uruguay’s Diversity March, 2022. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marcha_diversidad,_montevideo,_uruguay.jpg

But a recent change at the top does not bode well. Spokesperson for the Diversity March Coordinating Organization, Daniela Buquet, notes that the center-right government of President Luis Lacalle Pou (since 2020) is not implementing legal gains such as the Trans labor quota, gender-appropriate medical care, prevention of hate crimes or education on sexual and gender diversity. This is particularly difficult in more marginal areas of the country.

Final notable developments come from a country that was governed from the Right during the Pink Tide: the current leftist president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, came into office with a decade-long track record of supporting the LGBTQ+ community as mayor of Bogotá. His administration’s highly inclusive approach was dramatically symbolized by the presidential palace displaying pride flags to commemorate Pride month. Petro also removed the outspoken conservative Christian national police chief who notoriously blamed gay men for infecting police with HIV/AIDS and called homosexuality a “choice.”

Reflecting a trend to institutionalize representation, Petro’s government has included LGBTQ+ representatives in the national development planning process; appointed “out” leaders to decisionmaking positions; and promoted outreach from state ministries. In fact, there are so many inclusion efforts that there may be overlaps in the functions of the new office for Sexual and Gender Diversity—under Vice President Francia Márquez, a human-rights and environmental activist and lawyer and the first Afro-Colombian elected to executive office—and the Human Rights office of the Ministry of the Interior. In addition, the well-funded Ministry of Equality and Equity, also headed up by Márquez, has a LGBTIQ+ Vice Ministry.

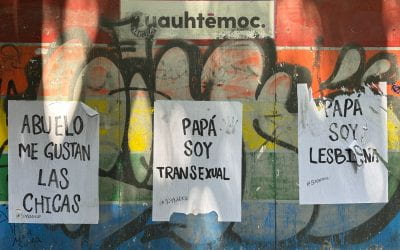

Despite these initiatives, the community faces an uphill battle. As Wilson Castaneda, director of Caribe Afirmativo, explains, right-wing opposition continues to object to “gender ideology…to associate the struggles of LGBTIQ+ with what is illegal, what is incorrect, with what goes against religion, the traditional family and individual freedoms.” Having the Left in power can make a significant difference for LGBTQ+ rights and recognition. But many on the Right continue to see those rights as wrong.

Demonstrators with a banner saying “Gender Ideology Never Again”, “#Don’tMessWithMyChildren”, Marcha por la Vida, 2018, Peru. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marcha_por_la_Vida_2018_Per%C3%BA_%285%29.jpg

Elisabeth Jay Friedman is Professor of Politics at the University of San Francisco. She is the editor of Seeking Rights from the Left (Duke University Press 2019). Her current research focuses on the impact of new generations and transnational ideas on feminist communities and strategies.

Kalena G. Peña, the research assistant for this article, is a Senior Politics major and Legal Studies minor at the University of San Francisco.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.